CHILDREN'S GAMES.

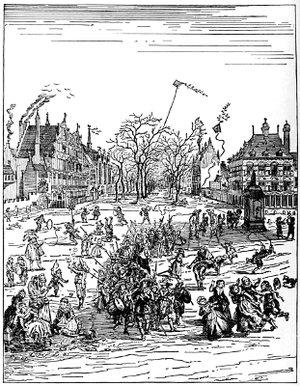

[From an old engraving by Van der Venne.]

Project Gutenberg's Games and Songs of American Children, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Games and Songs of American Children Author: Various Release Date: May 26, 2014 [EBook #45762] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GAMES, SONGS OF AMERICAN CHILDREN *** Produced by Richard Tonsing, David Edwards and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

CHILDREN'S GAMES.

[From an old engraving by Van der Venne.]

COLLECTED AND COMPARED

BY

WILLIAM WELLS NEWELL

NEW YORK

HARPER & BROTHERS, PUBLISHERS

1884

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1883, by

HARPER & BROTHERS,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

All rights reserved.

The existence of any children's tradition in America, maintained independently of print, has hitherto been scarcely noticed. Yet it appears that, in this minor but curious branch of folk-lore, the vein in the United States is both richer and purer than that so far worked in Great Britain. These games supply material for the elucidation of a subject hitherto obscure: they exhibit the true relation of ancient English lore of this kind to that of the continent of Europe; while the amusements of youth in other languages are often illustrated by American custom, which compares favorably, in respect of compass and antiquity, with that of European countries.

Of the two branches into which the lore of the nursery may be divided—the tradition of children and the tradition of nurses—the present collection includes only the former. It is devoted to formulas of play which children have preserved from generation to generation, without the intervention, often without the knowledge, of older minds. Were these—trifling as they often are—merely local and individual, they might be passed over with a smile; but being English and European, they form not the least curious chapter of the history of manners and customs. It has therefore been an essential part of the editor's object to exhibit their correspondences and history; but, unwilling to overcloud with cumbrous research that healthy and bright atmosphere which invests all that really belongs to childhood, he has thought it best to remand to an appendix the necessary references, retaining in the text only so much as may be reasonably supposed of interest to the readers in whom one or another page may awaken early memories.

He has to express sincere thanks to the friends, in different parts of the country, whose kind assistance has rendered possible this volume, in which almost every one of the older states is represented; and he will be grateful for such further information as may tend to render the collection more accurate and complete.

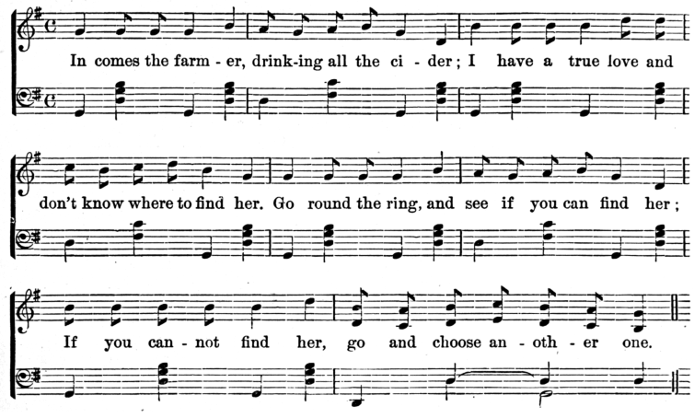

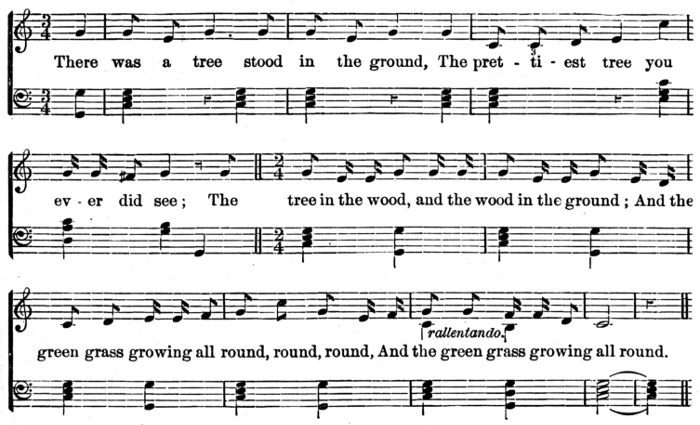

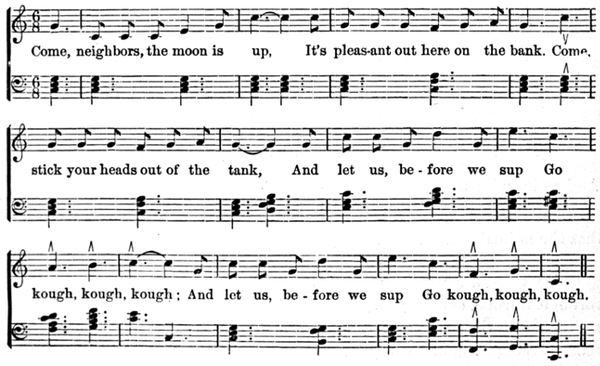

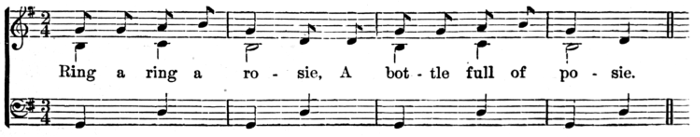

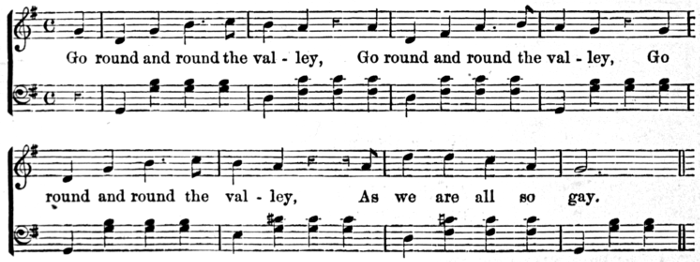

The melodies which accompany many of the games have been written from the recitation of children by S. Austen Pearce, Mus. Doc. Oxon.

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

| Editor's Note. | v | |

| INTRODUCTORY. | ||

| I. | The Diffusion and Origin of American Game-rhymes. | 1 |

| II. | The Ballad, the Dance, and the Game. | 8 |

| III. | May-games. | 13 |

| IV. | The Inventiveness of Children. | 22 |

| V. | The Conservatism of Children. | 28 |

| I. LOVE-GAMES. | ||

| No. | ||

| 1. | Knights of Spain. | 39 |

| 2. | Three Kings. | 46 |

| 3. | Here Comes a Duke. | 47 |

| 4. | Tread, Tread the Green Grass. | 50 |

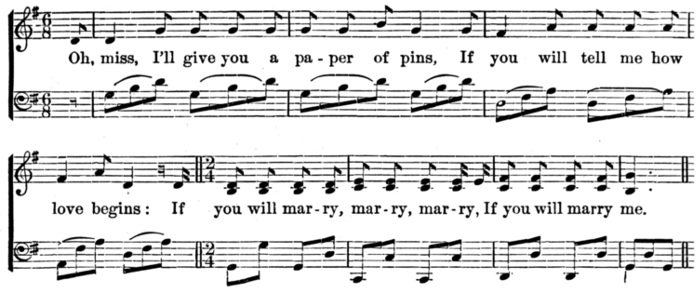

| 5. | I will Give You a Paper of Pins. | 51 |

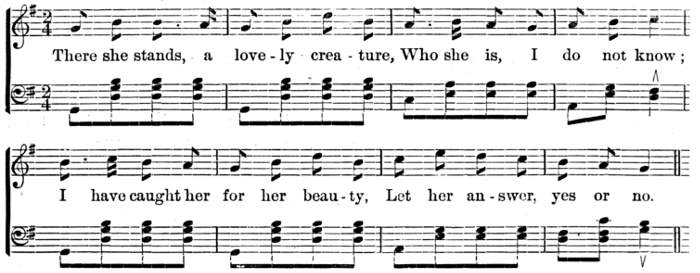

| 6. | There She Stands, a Lovely Creature. | 55 |

| 7. | Green Grow the Rushes, O! | 56 |

| 8. | The Widow with Daughters to Marry. | 56 |

| 9. | Philander's March. | 58 |

| 10. | Marriage. | 59 |

| II. HISTORIES. | ||

| 11. | Miss Jennia Jones. | 63 |

| 12. | Down She Comes, as White as Milk. | 67 |

| 13. | Little Sally Waters. | 70 |

| 14. | Here Sits the Queen of England. | 70 |

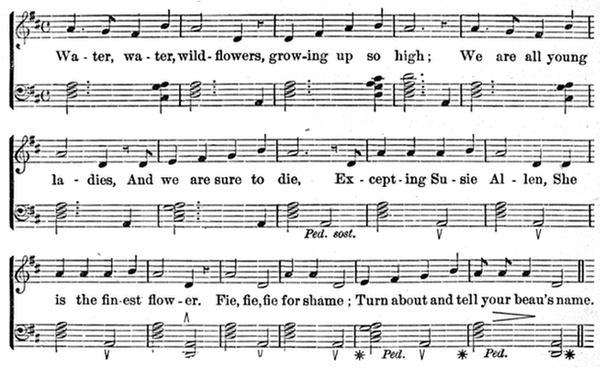

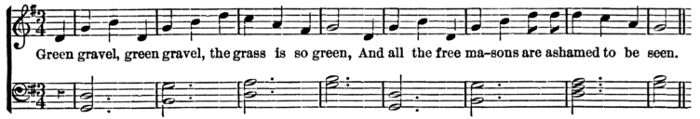

| 15. | Green Gravel. | 71 |

| 16. | Uncle John. | 72 |

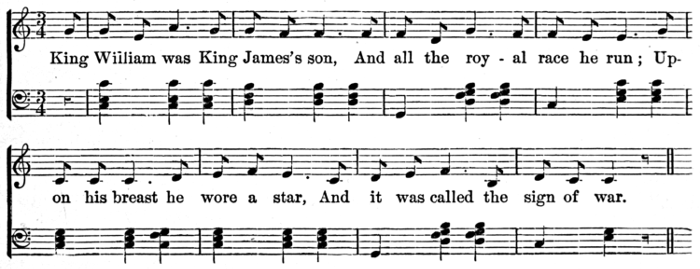

| 17. | King Arthur was King William's Son. | 73 |

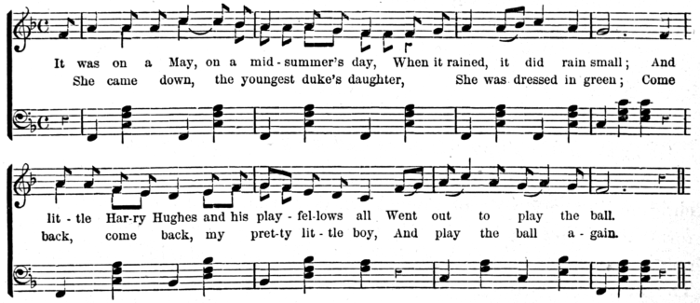

| 18. | Little Harry Hughes and the Duke's Daughter. | 75 |

| 19. | Barbara Allen. | 78 |

| III. PLAYING AT WORK. | ||

| 20. | Virginia Reel. | 80 |

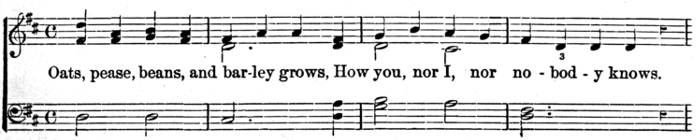

| 21. | Oats, Pease, Beans, and Barley Grows. | 80 |

| 22. | Who'll be the Binder? | 84 |

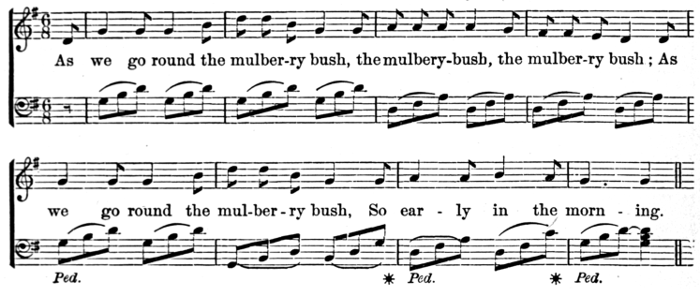

| 23. | As We Go Round the Mulberry Bush. | 86 |

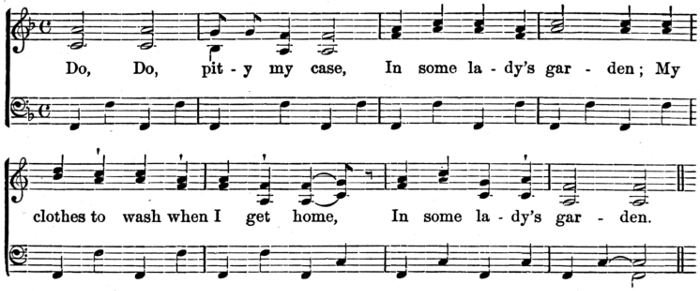

| 24. | Do, do, Pity my Case. | 87 |

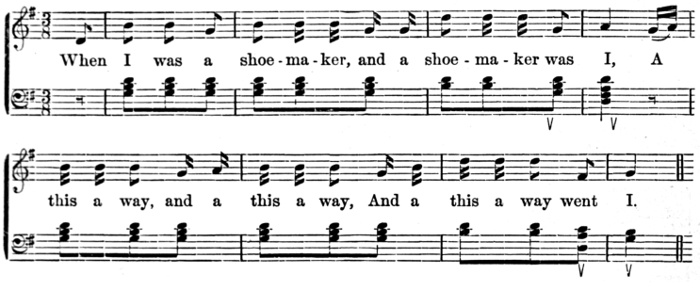

| 25. | When I was a Shoemaker. | 88 |

| 26. | Here we Come Gathering Nuts of May. | 89 |

| 27. | Here I Brew and Here I Bake. | 90 |

| 28. | Draw a Bucket of Water. | 90 |

| 29. | Threading the Needle. | 91 |

| IV. HUMOR AND SATIRE. | ||

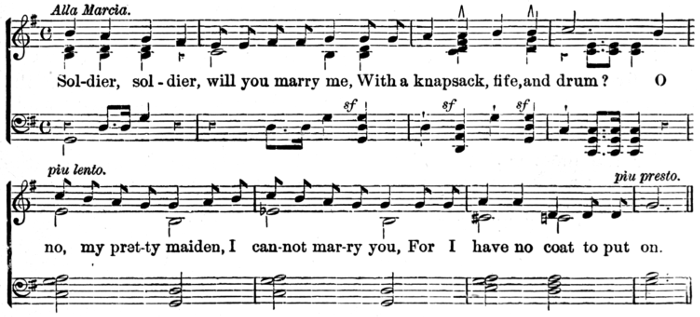

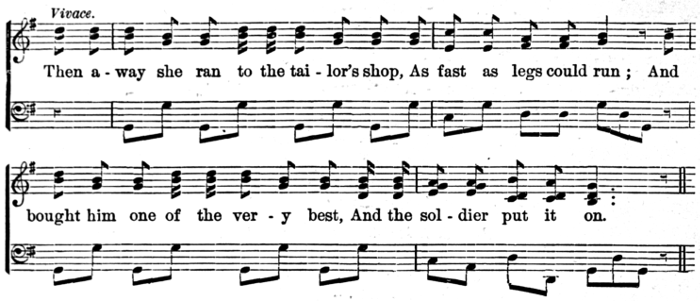

| 30. | Soldier, Soldier, Will You Marry Me? | 93 |

| 31. | Quaker Courtship. | 94 |

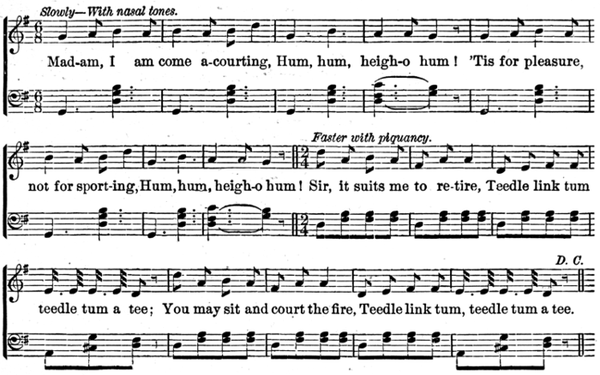

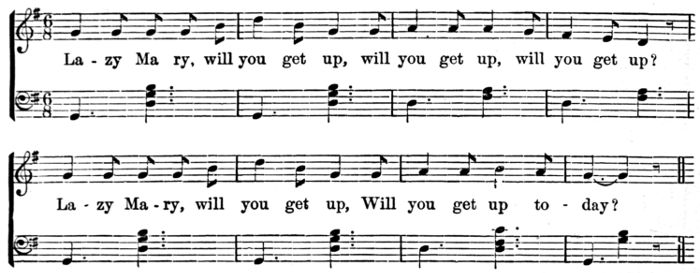

| 32. | Lazy Mary. | 96 |

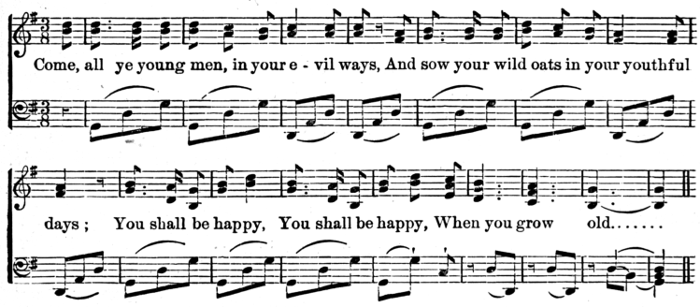

| 33. | Whistle, Daughter, Whistle. | 96 |

| 34. | There were Three Jolly Welshmen. | 97 |

| 35. | A Hallowe'en Rhyme. | 98 |

| 36. | The Doctor's Prescription. | 99 |

| 37. | Old Grimes. | 100 |

| 38. | The Baptist Game. | 101 |

| 39. | Trials, Troubles, and Tribulations. | 102 |

| 40. | Happy is the Miller. | 102 |

| 41. | The Miller of Gosport. | 103 |

| V. FLOWER ORACLES, ETC | ||

| 42. | Flower Oracles. | 105 |

| 43. | Use of Flowers in Games. | 107 |

| 44. | Counting Apple-seeds. | 109 |

| 45. | Rose in the Garden. | 110 |

| 46. | There was a Tree Stood in the Ground. | 111 |

| 47. | Green! | 113 |

| VI. BIRD AND BEAST. | ||

| 48. | My Household. | 115 |

| 49. | Frog-pond. | 116 |

| 50. | Bloody Tom. | 117 |

| 51. | Blue-birds and Yellow-birds. | 118 |

| 52. | Ducks Fly. | 119 |

| VII. HUMAN LIFE. | ||

| 53. | King and Queen. | 120 |

| 54. | Follow your Leader. | 122 |

| 55. | Truth. | 122 |

| 56. | Initiation. | 122 |

| 57. | Judge and Jury. | 123 |

| 58. | Three Jolly Sailors. | 124 |

| 59. | Marching to Quebec. | 125 |

| 60. | Sudden Departure. | 126 |

| 61. | Scorn. | 126 |

| VIII. THE PLEASURES OF MOTION. | ||

| 62. | Ring Around the Rosie. | 127 |

| 63. | Go Round and Round the Valley. | 128 |

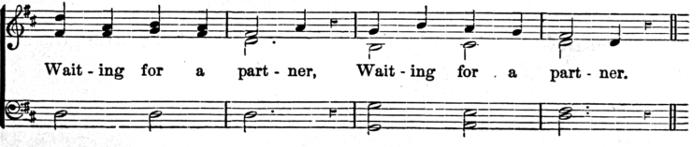

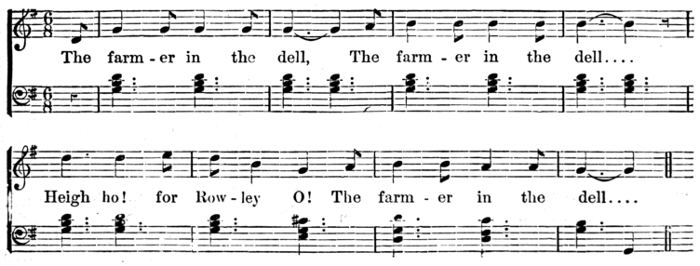

| 64. | The Farmer in the Dell. | 129 |

| 65. | The Game of Rivers. | 130 |

| 66. | Quaker, How is Thee? | 130 |

| 67. | Darby Jig. | 131 |

| 68. | Right Elbow In. | 131 |

| 69. | My Master Sent Me. | 131 |

| 70. | Humpty Dumpty. | 132 |

| 71. | Pease Porridge Hot. | 132 |

| 72. | Rhymes for a Race. | 132 |

| 73. | Twine the Garland. | 133 |

| 74. | Hopping-dance. | 133 |

| IX. MIRTH AND JEST. | ||

| 75. | Club Fist. | 134 |

| 76. | Robin's Alive. | 135 |

| 77. | Laughter Games. | 136 |

| 78. | Bachelor's Kitchen. | 137 |

| 79. | The Church and the Steeple. | 138 |

| 80. | What Color? | 138 |

| 81. | Beetle and Wedge. | 138 |

| 82. | Present and Advise. | 139 |

| 83. | Genteel Lady. | 139 |

| 84. | Beast, Bird, or Fish. | 140 |

| 85. | Wheel of Fortune. | 140 |

| 86. | Catches. | 141 |

| 87. | Intery Mintery. | 142 |

| 88. | Redeeming Forfeits. | 143 |

| 89. | Old Mother Tipsy-toe. | 143 |

| 90. | Who Stole the Cardinal's Hat? | 145 |

| X. GUESSING-GAMES. | ||

| 91. | Odd or Even. | 147 |

| 92. | Hul Gul. | 147 |

| 93. | How Many Fingers? | 148 |

| 94. | Right or Left. | 149 |

| 95. | Under which Finger? | 149 |

| 96. | Comes, it Comes. | 150 |

| 97. | Hold Fast My Gold Ring. | 150 |

| 98. | My Lady Queen Anne. | 151 |

| 99. | The Wandering Dollar. | 151 |

| 100. | Thimble in Sight. | 152 |

| XI. GAMES OF CHASE. | ||

| 101. | How Many Miles to Babylon? | 153 |

| 102. | Hawk and Chickens. | 155 |

| 103. | Tag. | 158 |

| 104. | Den. | 159 |

| 105. | I Spy. | 160 |

| 106. | Sheep and Wolf. | 161 |

| 107. | Blank and Ladder. | 161 |

| 108. | Blind-man's Buff. | 162 |

| 109. | Witch in the Jar. | 163 |

| 110. | Prisoner's Base. | 164 |

| 111. | Defence of the Castle. | 164 |

| 112. | Lil Lil. | 165 |

| 113. | Charley Barley. | 165 |

| 114. | Milking-pails. | 166 |

| 115. | Stealing Grapes. | 167 |

| 116. | Stealing Sticks. | 168 |

| 117. | Hunt the Squirrel. | 168 |

| XII. CERTAIN GAMES OF VERY LITTLE GIRLS. | ||

| 118. | Sail the Ship. | 170 |

| 119. | Three Around. | 170 |

| 120. | Iron Gates. | 170 |

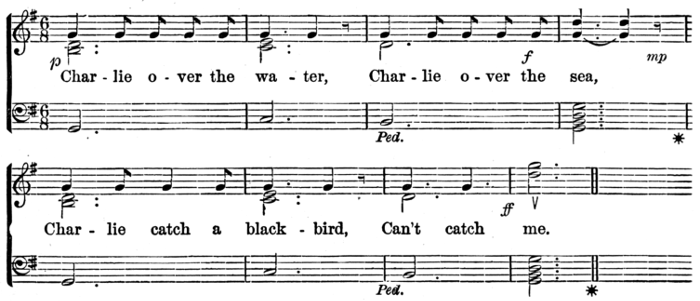

| 121. | Charley Over the Water. | 171 |

| 122. | Frog in the Sea. | 171 |

| 123. | Defiance. | 172 |

| 124. | My Lady's Wardrobe. | 173 |

| 125. | Housekeeping. | 173 |

| 126. | A March. | 174 |

| 127. | Rhymes for Tickling. | 174 |

| XIII. BALL, AND SIMILAR SPORTS. | ||

| 128. | The "Times" of Sports. | 175 |

| 129. | Camping the Ball. | 177 |

| 130. | Hand-ball. | 178 |

| 131. | Stool-ball. | 179 |

| 132. | Call-ball. | 181 |

| 133. | Haley-over. | 181 |

| 134. | School-ball. | 182 |

| 135. | Wicket. | 182 |

| 136. | Hockey. | 182 |

| 137. | Roll-ball. | 183 |

| 138. | Hat-ball. | 183 |

| 139. | Corner-ball. | 183 |

| 140. | Base-ball. | 184 |

| 141. | Marbles. | 185 |

| 142. | Cat. | 186 |

| 143. | Cherry-pits. | 187 |

| 144. | Buttons. | 187 |

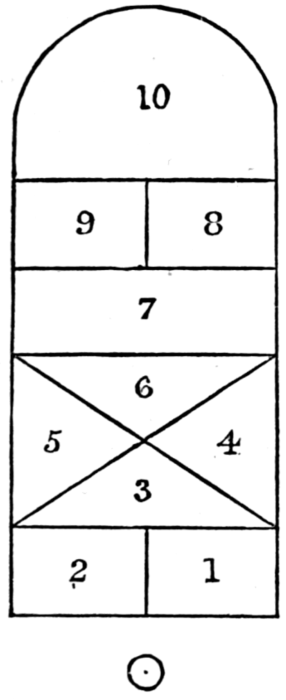

| 145. | Hop-Scotch. | 188 |

| 146. | Duck on a Rock. | 189 |

| 147. | Mumblety-peg. | 189 |

| 148. | Five-stones. | 190 |

| XIV. RHYMES FOR COUNTING OUT. | ||

| 149. | Counting Rhymes. | 194 |

| XV. MYTHOLOGY. | ||

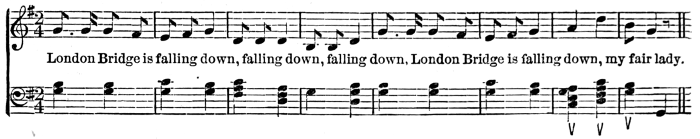

| 150. | London Bridge. | 204 |

| 151. | Open the Gates. | 212 |

| 152. | Weighing. | 212 |

| 153. | Colors. | 213 |

| 154. | Old Witch. | 215 |

| 155. | The Ogree's Coop. | 221 |

| 156. | Tom Tidler's Ground. | 221 |

| 157. | Dixie's Land. | 222 |

| 158. | Ghost in the Cellar. | 223 |

| 159. | The Enchanted Princess. | 223 |

| 160. | The Sleeping Beauty. | 224 |

| APPENDIX. | ||

| Collections of Children's Games. | 229 | |

| Comparisons and References. | 232 | |

GAMES AND SONGS

OF

AMERICAN CHILDREN.

"The hideous Thickets in this place[1] were such that Wolfes and Beares nurst up their young from the eyes of all beholders in those very places where the streets are full of Girles and Boys sporting up and downe, with a continued concourse of people."—"Wonder-working Providence in New England," 1654.

"The first settlers came from England, and were of the middle rank, and chiefly Friends. * * * In early times weddings were held as festivals, probably in imitation of such a practice in England. Relations, friends, and neighbors were generally invited, sometimes to the amount of one or two hundred. * * * They frequently met again next day; and being mostly young people, and from under restraint, practised social plays and sports."—Watson's "Account of Buckingham and Solebury" (Pennsylvania; settled about 1682).

A majority of the games of children are played with rhymed formulas, which have been handed down from generation to generation. These we have collected in part from the children themselves, in greater part from persons of mature age who remember the usages of their youth; for this collection represents an expiring custom. The vine of oral tradition, of popular poetry, which for a thousand years has twined and bloomed on English soil, in other days enriching with color and fragrance equally the castle and the cottage, is perishing at the roots; its prouder branches have long since been blasted, and children's song, its humble but longest-flowering offshoot, will soon have shared their fate.

It proves upon examination that these childish usages of play are almost [Pg 2]entirely of old English origin. A few games, it is true, appear to have been lately imported from England or Ireland, or borrowed from the French or the German; but these make up only a small proportion of the whole. Many of the rounds still common in our cities, judging from their incoherence and rudeness, might be supposed inventions of "Arabs of the streets;" but these invariably prove to be mere corruptions of songs long familiar on American soil. The influence of print is here practically nothing; and a rhyme used in the sports of American children almost always varies from the form of the same game in Great Britain, when such now exists.

There are quarters of the great city of New York in which one hears the dialect, and meets the faces, of Cork or Tipperary. But the children of these immigrants attend the public school, that mighty engine of equalization; their language has seldom more than a trace of accent, and they adopt from schoolmates local formulas for games, differing more or less from those which their parents used on the other side of the sea. In other parts of the town, a German may live for years, needing and using in business and social intercourse no tongue but his own, and may return to Europe innocent of any knowledge of the English speech. Children of such residents speak German in their homes, and play with each other the games they have brought with them from the Fatherland. But they all speak English also, are familiar with the songs which American children sing, and employ these too in their sports. There is no transference from one tongue to another, unless in a few cases, when the barrier of rhyme does not exist. The English-speaking population, which imposes on all new-comers its language, imposes also its traditions, even the traditions of children.

A curious inquirer who should set about forming a collection of these rhymes, would naturally look for differences in the tradition of different parts of the Union, would desire to contrast the characteristic amusements of children in the North and in the South, descendants of Puritan and Quaker. In this he would find his expectations disappointed, and for the reason assigned. This lore belongs, in the main, to the day before such distinctions came into existence; it has been maintained with equal pertinacity, and with small variations, from Canada to the Gulf. Even in districts distinguished by severity of moral doctrines, it does not appear that any attempt was made to interfere with the liberty of youth. Nowhere have the old sports (often, it is true, in crude rustic forms) been[Pg 3] more generally maintained than in localities famous for Puritanism. Thus, by a natural law of reversion, something of the music, grace, and gayety of an earlier period of unconscious and natural living has been preserved to sweeten the formality, angularity, and tedium of an otherwise beneficial religious movement.

It is only within the century that America has become the land of motion and novelty. During the long colonial period, the quiet towns, less in communication with distant settlements than with the mother-country itself, removed from the currents of thought circulating in Europe, were under those conditions in which tradition is most prized and longest maintained. The old English lore in its higher branches, the ballad and the tale, already belonging to the past at the time of the settlement, was only sparingly existent among the intelligent class from which America was peopled; but such as they did bring with them was retained. Besides, the greater simplicity and freedom of American life caused, as it would seem, these childish amusements to be kept up by intelligent and cultivated families after the corresponding class in England had frowned them down as too promiscuous and informal. But it is among families with the greatest claims to social respectability that our rhymes have, in general, been best preserved.

During the time of which we are writing, independent local usages sprang up, so that each town had oftentimes its own formulas and names for children's sports; but these were, after all, only selections from a common stock, one place retaining one part, another, of the old tradition. But in the course of the last two generations (and this is a secondary reason for the uniformity of our games in different parts of the country) the extension of intercourse between the States has tended to diffuse them, so that petty rhymes, lately invented, have sometimes gained currency from Maine to Georgia.

We proceed to speak of our games as they exist on the other side of the sea. A comparison with English and Scotch collections shows us very few games mentioned as surviving in Great Britain which we cannot parallel in independent forms. On the other hand, there are numerous instances in which rhymes of this sort, still current in America, do not appear to be now known in the mother-country, though they oftentimes have equivalents on the continent of Europe. In nearly all such cases it is plain that the New World has preserved what the Old World has forgotten; and the amusements of children to-day picture to us the dances[Pg 4] which delighted the court as well as the people of the Old England before the settlement of the New.[2]

To develop the interest of our subject, however, we must go beyond the limits of the English tongue. The practice of American children enables us to picture to ourselves the sports which pleased the infancy of Froissart and Rabelais.[3] A dramatic action of the Virginia hills preserves the usage of Färöe and Iceland, of Sweden and Venice.[4] We discover that it is an unusual thing to find any remarkable childish sport on the European continent which failed to domesticate itself (though now perhaps forgotten) in England. It is thus vividly and irresistibly forced upon our notice, that the traditions of the principal nations of Europe have differed little more than the dialects of one language, the common tongue, so to speak, of religion, chivalry, and civilization.

A different explanation has been given to this coincidence. When only the agreement, in a few cases, of English and German rhymes was noticed, it was assumed that the correspondence was owing to race-migration; to the settlement in England of German tribes, who brought with them national traditions. The present volume would be sufficient to show the untenability of such an hypothesis. The resemblance of children's songs in different countries, like the similarity of popular traditions in general, is owing to their perpetual diffusion from land to land; a diffusion which has been going on in all ages, in all directions, and with all degrees of rapidity. But the interest of their resemblance is hardly diminished by this consideration. The character of some of these parallelisms proves that for the diffusion in Europe of certain games of our collection we must go back to the early Middle Age;[5] while the extent of the identity of our American (that is, of old English) child's lore with the European is a continual surprise.[6]

Internal evidence alone would be sufficient to refer many of the sports to a mediæval origin, for we can still trace in them the expression of the life of that period.

We comprehend how deeply mediæval religious conceptions affected the life of the time, when we see that allusions to those beliefs are still concealed in the playing of children. We find that the tests which the soul, escaped from the body, had, as it was supposed, to undergo—the scales of St. Michael, the keys of St. Peter, and the perpetual warfare of angels and devils over departed souls—were familiarly represented and dramatized in the sports of infants.[7] Such allusions have, it is true, been excluded from English games; but that these once abounded with them can be made abundantly evident. We see that chivalric warfare, the building and siege of castles, the march and the charge of armies, equally supplied material for childish mimicry. We learn how, in this manner, the social state and habits of half a thousand years ago unconsciously furnish the amusement of youth, when the faith and fashion of the ancient day is no longer intelligible to their elders.

It will be obvious that many of the game-rhymes in this collection were not composed by children. They were formerly played, as in many countries they are still played, by young persons of marriageable age, or even by mature men and women. The truth is, that in past centuries all the world, judged by our present standard, seems to have been a little childish. The maids of honor of Queen Elizabeth's day, if we may credit the poets, were devoted to the game of tag,[8] and conceived it a waste of time to pass in idleness hours which might be employed in that pleasure, with which Diana and her nymphs were supposed to amuse themselves. Froissart describes the court of France as amusing itself with sports familiar to his own childhood; and the Spectator speaks of the fashionable ladies of London as occupied with a game which is represented in this series.[9]

We need not, however, go to remote times or lands for illustration which is supplied by New England country towns of a generation since. In these, dancing, under that name, was little practised; it was confined to one or two balls in the course of the year on such occasions as the Fourth of July, lasting into the morning hours. At other times, the amusement of young people at their gatherings was "playing games." These games generally resulted in forfeits, to be redeemed by kissing, in every possible variety of position and method. Many of these games were rounds; but as they were not called dances, and as mankind pays more attention to words than things, the religious conscience of the community, which objected [Pg 6]to dancing, took no alarm. Such were the pleasures of young men and women from sixteen to twenty-five years of age. Nor were the participants mere rustics; many of them could boast as good blood, as careful breeding, and as much intelligence, as any in the land. Neither was the morality or sensitiveness of the young women of that day in any respect inferior to what it is at present.

Now that our country towns are become mere outlying suburbs of cities, these remarks may be read with a smile at the rude simplicity of old-fashioned American life. But the laugh should be directed, not at our own country, but at the by-gone age.[10] In respectable and cultivated French society, at the time of which we speak, the amusements, not merely of young people, but of their elders as well, were every whit as crude. The suggestion is so contrary to our preconceived ideas, that we hasten to shelter ourselves behind the respectable name of Madame Celnart, who, as a recognized authority on etiquette, must pass for an unimpeachable witness.[11] This writer compiled a very curious "Complete Manual of Games of Society, containing all the games proper for young people of both sexes," which seems to have gained public approbation, since it reached a second edition in 1830. In her preface she recommends the games of which we have been speaking as recreations for business men:

"Another consideration in favor of games of society: it must be admitted that for persons leading a sedentary life, and occupied all day in writing and reckoning (the case with most men), a game which demands the same attitude, the same tension of mind, is a poor recreation. * * * On the contrary, the varying movement of games of society, their diversity, the gracious and gay ideas which these games inspire, the decorous caresses which they permit—all this combines to give real amusement. These caresses can alarm neither modesty nor prudence, since a kiss in honor given and taken before numerous witnesses is often an act of propriety."

She prefers "rounds" to other amusements: "All hands united; all feet in cadence; all mouths repeating the same refrain; the numerous turns, the merry airs, the facile and rapid pantomime, the kisses which usually accompany them—everything combines, in my opinion, to make rounds the exercise of free and lively gayety."

We find among the ring-games given by our author, and recommended to men of affairs, several of which English forms exist in our collection, and are familiar to all children.[12]

We are thus led to remark an important truth. It is altogether a mistake to suppose that these games (or, indeed, popular lore of any description) originated with peasants, or describe the life of peasants. The tradition, on the contrary, invariably came from above, from the intelligent class. If these usages seem rustic, it is only because the country retained what the city forgot, in consequence of the change of manners to which it was sooner exposed. Such customs were, at no remote date, the pleasures of courts and palaces. Many games of our collection, on the other hand, have, it is true, always belonged to children; but no division-line can be drawn, since out of sports now purely infantine have arisen dances and songs which have for centuries been favorites with young men and women.[13]

Canadian Round.

Games accompanied by song may be divided into ballads, songs, and games proper.

By the term ballad is properly signified a dance-song, or dramatic poem sung and acted in the dance. The very word, derived through the late Latin[14] from the Greek, attests that golden chain of oral tradition which links our modern time, across centuries of invasion and conflict, with the bright life of classic antiquity.

Still more pleasantly is a like history contained in another name for the same custom. The usual old English name for the round dance, or its accompanying song, was carol, which we now use in the restricted sense of a festival hymn. Chaucer's "Romaunt of the Rose" describes for us the movement of the "karole," danced on the "grene gras" in the spring days. He shows us knights and ladies holding each other by the hand, in a flowery garden where the May music of mavis and nightingale blends with the "clere and ful swete karoling" of the lady who sings for the dancers. This sense of the word continued in classic use till the sixteenth century, and has survived in dialect to the present day. Many of the [Pg 9]games of our series are such rounds or carols, "love-dances" in which youths and maidens formerly stood in the ring by couples, holding each other's hands, though our children no longer observe that arrangement. Now the word carol is only a modernized form of chorus. Thus childish habit has preserved to the present day the idea and movement of the village ring-dance, the chorus, such as it existed centuries or millenniums before another and religious form of the dance accompanied by song had received that technical name in the Greek drama.

Very little was needed to turn the ballad into a dramatic performance, by assigning different parts to different actors. It is natural also for children to act out the stories they hear. We find, accordingly, that ancient ballads have sometimes passed into children's games. But, in the present collection, the majority of the pieces which can be referred to the ballad are of a different character. In these the remainder of the history is reduced to a few lines, or to a single couplet. These historiettes have retained the situation, omitting the narration, of the ancient song. We can understand how youthful or rustic minds, when the popular song had nearly passed out of mind, should have vaguely maintained the upshot of the story:

It is the tragedy told in a line; and what more is needed, since an excuse is already provided for the kiss or the romp?[15]

Of lyric song we have scarce anything to offer. The fifteenth and sixteenth centuries gave birth, all over Europe, to popular lyric poesy, modelled on literary antecedents, and replacing in general estimation the ancient dramatic ballad. Shakespeare, who merely refers to the ballad proper, makes frequent use of the popular song of his day. In many countries this taste has penetrated to the people; the power of lyric composition has become general, so that a collection of popular songs will contain many sweet and pleasing pieces. The ballad has thus passed into the round. An inconsequent but musical babble, like that of a brook or a child, has replaced the severe accents of the ancient narration. But in English—why, we will not pause to inquire—it is not so. Whatever of this kind once existed has passed away, leaving but little trace. All that is poetical or pretty is the relic of past centuries; and when the ancient [Pg 10]treasure is spent, absolute prose succeeds. The modern soil is incapable of giving birth to a single flower.

Our rhymes, therefore, belong almost entirely to the third class—the game proper. But though less interesting poetically, and only recorded at a late period, it does not follow that they have not as ancient a history as the oldest ballads; on the contrary, it will abundantly appear that the formulas used in games have an especially persistent life. As the ballad is a dramatic narrative, so the game is a dramatic action, or series of actions; and the latter is as primitive as the former, while both were employed to regulate the dance.

Most modern dances, silently performed in couples, are merely lively movements; but in all ancient performances of the sort the idea is as essential as the form. Precisely as the meaningless refrains of many ballads arise from a forgetfulness of intelligible words, dances which are only motion grew out of dances which expressed something. The dance was originally the dramatized expression of any feature of nature or life which excited interest. Every department of human labor—the work of the farmer, weaver, or tradesman; the church, the court, and the army; the habits and movements of the animals which seem so near to man in his simplicity, and in whose life he takes so active an interest; the ways and works of the potent supernatural beings, good or evil, or, rather, beneficent or dangerous, by whom he believes himself surrounded; angel and devil, witch and ogre—representations of all these served, each in turn, for the amusement of an idle hour, when the labor which is the bitterness of the enforced workman is a jest to the free youth, and the introduction of spiritual fears which constitute the terror of darkness only adds an agreeable excitement to the sports of the play-ground. All this was expressed in song shared by the whole company, which was once the invariable attendant of the dance, so that the two made up but one idea, and to "sing a dance" and "dance a song" were identical expressions.

The children's rounds of to-day, in which each form of words has its accompanying arrangement of the ring, its significant motion and gesture, thus possess historic interest. For these preserve for us some picture of the conduct of the ballads, dances, and games which were once the amusement of the palace as of the hamlet.

The form of the verses used in the games also deserves note. These usually consist either of a rhyming couplet, or of four lines in which the second and fourth rhyme; they are often accompanied by a refrain, which[Pg 11] may be a single added line, or may be made up of two lines inserted into the stanza; and in place of exact consonance, any assonance, or similarity of sound, will answer for the rhyme. Above all, they possess the freedom and quaintness, the tendency to vary in detail while preserving the general idea, which distinguish a living oral tradition from the monotonous printed page; in these respects, our rhymes, humble though they be, are marked as the last echo of the ancient popular poetry.

There is especial reason why an Englishman, or the descendants of Englishmen, should take pride in the national popular song.[16] European mediæval tradition was, it is true, in a measure a common stock; but, though the themes may often have been thus supplied, the poetic form which was given to that material in each land was determined by the genius of the language and of the people. Now, among all its neighbors, the English popular poesy was the most courtly, the most lyric, the most sweet. So much we can still discern by what time has spared.

The English ballad was already born when Canute the Dane coasted the shore of Britain; its golden age was already over when Dante summed up mediæval thought in the "Divina Commedia;" its reproductive period was at an end when Columbus enlarged the horizon of Europe to admit a New World; it was a memory of the past when the American colonies were founded; but even in its last echoes there lingers we know not what mysterious charm of freshness, poetic atmosphere, and eternal youth. Even in these nursery rhymes some grace of the ancient song survives. A girl is a "red rose," a "pretty fair maid," the "finest flower," the "flower of May." The verse itself, simple as it is, often corrupted, is a cry of delight in existence, of satisfaction with nature; its season is the season of bloom and of love; its refrain is "For we are all so gay." It comes to us, in its innocence and freshness, like the breath of a distant and inaccessible garden, tainted now and then by the odors of intervening city streets. But the vulgarity is modern, accidental; the pleasure and poetry are of the original essence.

We cannot but look with regret on the threatened disappearance of these childish traditions, which have given so much happiness to so many generations, and which a single age has nearly forgotten. These songs [Pg 12]have fulfilled the conditions of healthy amusement, as nothing else can do. The proper performance of the round, or conduct of the sport, was to youthful minds a matter of the most serious concern—a little drama which could be represented over and over for hours, in which self-consciousness was absorbed in the ambition of the actors to set forth properly their parts. The recital had that feature which distinguishes popular tradition in general, and wherein it is so poorly replaced by literature. Here was no repetition by rote; but the mind and heart were active, the spirit of the language appropriated, and a vein of deep though childish poetry nourished sentiment and imagination. It seems a thousand pities that the ancient tree should not continue to blossom; that whatever may have been acrid or tasteless in the fruit cannot be corrected by the ingrafting of a later time. There is something so agreeable in the idea of an inheritance of thought kept up by childhood itself, created for and adapted to its own needs, that it is hard to consent to part with it. The loss cannot be made good by the deliberate invention of older minds. Children's amusement, directed and controlled by grown people, would be neither childish nor amusing. True child's play is a sacred mystery, at which their elders can only obtain glances by stealth through the crevice of the curtain. Children will never adopt as their own tradition the games which may be composed or remodelled, professedly for their amusement, but with the secret purpose of moral direction.

We do not mean, however, to sigh over natural changes. These amusements came into existence because they were adapted to the conditions of early life; they pass away because those conditions are altered. The taste of other days sustained them; the taste of our day abandons them. This surrender is only one symptom of a mighty change which has come over the human mind, and which bids fair to cause the recent time, a thousand years hence, to be looked back upon as a dividing-mark in the history of intelligence. If it should turn out that the childhood of the human intellect is passing gradually into the "light of common day"—if the past is to be looked back upon with that affectionate though unreasoning interest with which a grown man remembers his imaginative youth—then every fragment which illustrates that past will possess an attraction independent of its intrinsic value.

Old Song.

Children's rhymes and songs have been handed down in two principal ways. First, they have been used for winter amusements, particularly at the Christmas season,[17] as has from time immemorial been the case in northern countries; and, secondly, they have been sung as rounds and dances, especially during summer evenings, upon the village green or city sidewalk. The latter custom is fast becoming extinct, though the circling ring of little girls "on the green grass turning" may now and then be still observed; but a generation since the practice was common with all classes. The proper time for such sports is the early summer; and many of our rounds declare themselves in words, as well as by sentiment, to be the remainder of the ancient May dances. To render this clear, it will be necessary to give some account of the May festival; but we shall confine ourselves to customs of which we can point out relics in our own land. These we can illustrate, without repeating the descriptions of English writers, from Continental usage, which was in most respects identical with old English practice.

It was an ancient habit for the young men of a village, on the eve of the holiday, to go into the forests and select the tallest and straightest tree [Pg 14]which could be found. This was adorned with ribbons and flowers, brought home with great ceremony, and planted in front of the church, or at the door of some noted person, where it remained permanently to form the centre of sports and dances. The May-pole itself, the songs sung about it, and the maiden who was queen of the feast, were alike called May. In the absence of any classic mention, the universality of the practice in mediæval Europe, and the common Latin name, may be taken as proof that similar usages made part of the festival held about the calends of May—the Floralia or Majuma.

Notwithstanding all that has been said about the license of this festival in the days of the Empire, it is altogether probable that the essential character of the feast of Flora or Maia was not very different from its mediæval or modern survival. The abundance of flowers, the excursions to the mountains, the decoration of houses, and the very name of Flora, prove that, whatever abuses may have introduced themselves, and whatever primitive superstitions may have been intermingled—superstitions to an early time harmless and pure, and only in the decline of faith the source of offence and corruption—the population of ancient Italy shared that natural and innocent delight in the season of blossom which afterwards affected to more conscious expression Chaucer and Milton.

This "bringing home of summer and May" was symbolic; the tree, dressed out in garlands, typifying the fertility of the year. As in all such rites, the songs and dances, of a more or less religious character, were supposed to have the power of causing the productiveness which they extolled or represented.[18] These practices, however, were not merely superstitious; mirth and music expressed the delight of the human heart, in its simplicity, at the reappearance of verdure and blossom, and thanksgiving to the generous Bestower, which, so long as man shall exist on earth, will be instinctively awakened by the bright opening of the annual drama. Superstition has been the support about which poetry has twined: it is a common mistake of investigators to be content with pointing out the former, and overlooking the coeval existence of the latter. Thus the natural mirth and merriment of the season blended with the supposed efficacy of the rite; and the primitive character of the ring-dance appears to be the circle about the sacred tree in honor of the period of bloom.

A relic, though a trifling one, of the ancient custom, may be seen in [Pg 15]some of our cities on the early days of the month. In New York, at least, groups of children may then be observed carrying through the streets a pole painted with gay stripes, ribbons depending from its top, which are held at the end by members of the little company. These proceed, perhaps, to the Central Park, where they conduct their festivities, forming the ring, and playing games which are included in our collection. Within a few years, however, these afternoon expeditions have become rare.

The May-pole, as we have described it, belonged to the village; but a like usage was kept up by individuals. It was the duty of every lover to go into the woods on the eve or early morn of May-day, and bring thence boughs and garlands, which he either planted before the door of his mistress, or affixed thereto, according to local custom. The particular tree, or bush (this expression meaning no more than bough), preferred for the purpose was the hawthorn, which is properly the tree of May, as blooming in the month the name of which it has in many countries received. A belief in the protective influence of the white-thorn, when attached to the house-door, dates back to Roman times. The May-tree, whatever its species, was often adorned with ribbons and silk, with fruit or birds, sometimes with written poems. The lover brought his offering at early dawn, and it was the duty of his mistress to be present at her window and receive it; thus we have in a song of the fifteenth or sixteenth century from the Netherlands—

An English carol alludes to the same practice—

The custom was so universal as to give rise to proverbial expressions. Thus, in Italy, "to plant a May at every door" meant to be very susceptible; and in France, to "esmayer" a girl was to court her.

Some of our readers may be surprised to learn that an offshoot of this [Pg 16]usage still exists in the United States; the custom, namely, of hanging "May baskets." A half-century since, in Western Massachusetts, a lad would rise early on May-morning, perhaps at three o'clock, and go into the fields. He gathered the trailing arbutus (the only flower there available at the season), and with his best skill made a "basket," by the aid of "winter-green" and similar verdure. This he cautiously affixed to the door of any girl whom he wished to honor. She was left to guess the giver. The practice is still common in many parts of the country, but in a different form. Both boys and girls make "May baskets," and on May-eve attach them to each other's doors, ringing at the same time the house-bell. A pursuit follows, and whoever can capture the responsible person is entitled to a kiss. We do not venture to assert that the latter usage is entirely a corruption of the former.[20]

The term "May-baskets" is no doubt a modernized form of the old English word "May-buskets," employed by Spenser.[21] Buskets are no more than bushes—that is, as we have already explained, the flowering branches of hawthorn or other tree, picked early on the May-morn, and used to decorate the house. It seems likely that a misunderstanding of the word changed the fashion of the usage; the American lad, instead of attaching a bough, hung a basket to his sweetheart's door.

A French writer pleasantly describes the customs of which we are speaking, as they exist in his own province of Champagne: "The hours have passed; it is midnight; the doors of the young lads open. Each issues noiselessly. He holds in his hand branches and bouquets, garlands and crowns of flowers. Above the gate of his mistress his hand, trembling with love, places his mysterious homage; then, quietly as he came, he retires, saying, 'Perhaps she has seen me.' ... The day dawns. Up! boys and girls! up! it is the first of May! up, and sing! The young [Pg 17]men, decked out with ribbons and wild-flowers, go from door to door to sing the month of May and their love."

Of the morning song and dance about the "bush," or branches of trees planted as we have described, we have evidence in the words of American rhymes. Thus—

In one or two instances, a similar refrain figures in the childish sports of little girls, who have probably got it by imitation; in others, it is the sign of an old May game.[22] An English writer of the sixteenth century alludes to the morning dance in a way which proves that these songs really represent the practice of his time.[23]

The playing of May games was by no means confined to the exact date of the festival. The sign of a country tavern in England was a thorn-bush fixed on a pole, and about this "bush" took place the dance of wedding companies who came to the tavern to feast, whence this post was called the bride's stake. Whether the thorn-bush was introduced into the "New English" settlements we cannot say; but the dancing at weddings was common, at least among that portion of those communities which was not bound by the religious restraint that controlled the ruling class. There were, as a French refugee wrote home in 1688, "all kinds of life and manners" in the colonies. In the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, 7th May, 1651, the General Court resolved, "Whereas it is observed that there are many abuses and disorders by dauncinge in ordinaryes, whether mixt or unmixt, upon marriage of some persons, this court doth order, that henceforward there shall be no dauncinge upon such occasion, or at other times, in ordinaryes, upon the paine of five shillings, for every person that shall so daunce in ordinaryes." While youth in the cities might be as gay as elsewhere, in many districts the Puritan spirit prevailed, and the very name of dancing was looked on with aversion. But the young people met this emergency with great discretion; they simply called their amusements playing games, and under this name kept up many of the rounds which were the time-honored dances of the old country.

The French writer whom we have already had occasion to quote goes on to speak of the customs of the younger girls of his province—the bachelettes, as they are called. "On the first of May, dressed in white, they put at their head the sweetest and prettiest of their number. They robe her for the occasion: a white veil, a crown of white flowers adorn her head; she carries a candle in her hand; she is their queen, she is the Trimouzette. Then, all together, they go from door to door singing the song of the Trimouzettes; they ask contributions for adorning the altar of the Virgin, for celebrating, in a joyous repast, the festival of the Queen of Heaven."

This May procession, which has been the custom of girls for centuries, from Spain to Denmark, existed, perhaps still exists, in New England. Until very recently, children in all parts of the United States maintained the ancient habit of rising at dawn of May-day, and sallying forth in search of flowers. The writer well remembers his own youthful excursions, sometimes rewarded, even in chilly Massachusetts, by the early blue star of the hepatica, or the pink drooping bell of the anemone. The maids, too, had rites of their own. In those days, troops of young girls might still be seen, bareheaded and dressed in white, their May-queen crowned with a garland of colored paper. But common-sense has prevailed at last over poetic tradition; and as an act of homage to east winds, a hostile force more powerful at that period than the breath of Flora, it has been agreed that summer in New England does not begin until June.

These May-day performances, however, were originally no children's custom; in this, as in so many other respects, the children have only proved more conservative of old habit than their elders. There can be no doubt that these are the survivals of the ancient processions of Ceres, Maia, Flora, or by whatever other name the "good goddess," the patroness of the fertile earth, was named, in which she was solemnly borne forth to view and bless the fields. The queen of May herself represents the mistress of Spring; she seems properly only to have overlooked the games in which she took no active part.[24]

A writer of the fifteenth century thus describes the European custom of his day: "A girl adorned with precious garments, seated on a chariot [Pg 19]filled with leaves and flowers, was called the queen of May; and the girls who accompanied her as her handmaidens, addressing the youths who passed by, demanded money for their queen. This festivity is still preserved in many countries, especially Spain." The usage survives in the dolls which in parts of England children carry round in baskets of flowers on May-day, requesting contributions.

Of this custom a very poetical example, not noticed by English collectors, has fallen under our own observation. We will suppose ourselves in Cornwall on May-day; the grassy banks of the sunken lanes are gay with the domestic blooms dear to old poetry; the grass is starry with pink and white daisies; the spreading limbs of the beech are clad in verdure, and among the budding elms of the hedge-rows "birds of every sort" "send forth their notes and make great mirth." A file of children, rosy-faced boys of five or six years, is seen approaching; their leader is discoursing imitative music on a wooden fife, to whose imaginary notes the rest keep time with dancing steps. The second and third of the party carry a miniature ship; its cargo, its rigging, are blooms of the season, bluebells and wall-flowers; the ship is borne from door to door, where stand the smiling farmers and their wives; none is too poor to add a penny to the store. As the company vanishes at the turn of the lane, we feel that the merriment of the children has more poetically rendered the charm of the season than even the song of the birds.

There is in America no especial song of the festival, though children at the May parties of which we have spoken still keep up the "springing and leaping" which mediæval writers speak of as practised by them at this occasion. Popular songs are, however, still remembered in Europe, where their burden is, May has come! or, Welcome to May! Pleasing and lyric is the song of the "Trimazos," the lay of the processions of girls to which we have alluded, though its simplicity becomes more formal in our version of the provincial French:

So, in the Vosges, young girls fasten a bough of laurel to the hat of a young man whom they may meet on the way, wishing

They ask a gift, but not for themselves:

Corresponding to the French song from which we have quoted is the English May carol, similarly sung from dwelling to dwelling:

The frequent allusions of the earlier English poets to "doing May observance," or the "rite of May," show us how all ranks of society, in their time, were still animated by the spirit of those primitive faiths to which we owe much of our sensibility to natural impressions. Milton himself, though a Puritan, appears to approve the usages of the season, and even employs the ancient feminine impersonation of the maternal tenderness and bounty of nature, invoking the month:

Time, and the changes of taste, have at last proved too strong for the persistency of custom; the practices by which blooming youth expressed its sympathy with the bloom of the year have perished, taking with them much of the poetry of the season, and that inherited sentiment which was formerly the possession of the ignorant as well as of the cultivated class.

Minnesinger, 13th Century.

The student of popular traditions is accustomed to recognize the most trifling incidents of a tale, or the phrases of a song, as an adaptation of some ancient or foreign counterpart, perhaps removed by an interval of centuries. It is the same with rhymes of the sort included in this collection, in which formulas of sport, current in our own day and in the New World, will be continually found to be the legacy of other generations and languages. Should we then infer that childhood, devoid of inventive capacity, has no resource but mechanical repetition?

We may, on the contrary, affirm that children have an especially lively imagination. Observe a little girl who has attended her mother for an airing in some city park. The older person, quietly seated beside the footpath, is half absorbed in revery; takes little notice of passers-by, or of neighboring sights or sounds, further than to cast an occasional glance which may inform her of the child's security. The other, left to her own devices, wanders contented within the limited scope, incessantly prattling to herself; now climbing an adjoining rock, now flitting like a bird from one side of the pathway to the other. Listen to her monologue, flowing as incessantly and musically as the bubbling of a spring; if you can catch enough to follow her thought, you will find a perpetual romance unfolding itself in her mind. Imaginary personages accompany her foot[Pg 23]steps; the properties of a childish theatre exist in her fancy; she sustains a conversation in three or four characters. The roughnesses of the ground, the hasty passage of a squirrel, the chirping of a sparrow, are occasions sufficient to suggest an exchange of impressions between the unreal figures with which her world is peopled. If she ascends, not without a stumble, the artificial rockwork, it is with the expressed solicitude of a mother who guides an infant by the edge of a precipice; if she raises her glance to the waving green overhead, it is with the cry of pleasure exchanged by playmates who trip from home on a sunshiny day. The older person is confined within the barriers of memory and experience; the younger breathes the free air of creative fancy.

A little older grown, such a child becomes the inventor of legend. Every house, every hill in the neighborhood, is the locality of an adventure. Every drive includes spots already famous in supposed history, and passes by the abodes of fancied acquaintances. Into a land with few traditions the imagination of six years has introduced a whole cycle of romance.

If the family or vicinity contains a group of such minds, fancy takes outward form in dramatic performance. The school history is vitalized into reality; wars are waged and battles performed in a more extended version, while pins and beans signify squadrons and regiments. Romances are acted, tales of adventure represented with distribution of rôles. Thus, in a family of our acquaintance, the children treasured up wood-engravings, especially such as were cut from the illustrated journals: runaway horses, Indian chiefs, and trappers of the wilderness were at an especial premium. These they stored in boxes, encamped in different corners of the room, and performed a whole library of sensational tales. A popular piece set forth the destruction of the villain of the story by a shark, while navigating a catamaran. The separated beds of the sleeping-room represented the open planks of the raft; the gentlest and most compliant character personified the malefactor; and the shark swam between the bedsteads.

Where sports require or allow such freedom, the ingenuity of children puts to shame the dulness of later years, and many a young lady of twenty would find it impossible to construct the dialogue which eight summers will devise without an effort. It was a favorite amusement of two girls just entering their teens to conduct a boarding-school. The scholars and the teachers of the imaginary school were all named, and these characters[Pg 24] were taken in dialogue by the little actors, each sustaining several perfectly well-defined parts. The pupils pursued their pleasures and their studies according to their several tastes; while their progress, their individual accomplishments and offences, were subsequently gravely discussed by the instructors, and the condition, prospects, and management of the institution talked over. Thus, hour after hour, without hesitation or weariness, the conversation proceeded, with the duo of friends for actors and audience!

Oftentimes, with young children, an outward support is required for fancy, an object to be mentally transformed. One set of little girls collected in the fall birch-leaves, changed to yellow, out of which alone they created their little nursery. Another party employed pins, which they inserted in a board, and called pin-fairies. By the aid of these, long dramatizations were performed, costumes devised, and palaces decorated, under regulations rigidly observed.

Such exercises of imagination are usually conducted in strict privacy, and unremarked, or not understood, by parents; but when the attention of the latter is directed to these performances, they are often astonished by the readiness they disclose, and are apt to mistake for remarkable talent what is only the ease of the winged fancy of youth, which flies lightly to heights where later age must laboriously mount step by step.

As infancy begins to speak by the free though unconscious combination of linguistic elements, so childhood retains in language a measure of freedom. A little attention to the jargons invented by children might have been serviceable to certain philologists. Their love of originality finds the tongue of their elders too commonplace; besides, their fondness for mystery requires secret ways of communication. They therefore often create (so to speak) new languages, which are formed by changes in the mother-speech, but sometimes have quite complicated laws of structure, and a considerable arbitrary element.

The most common of these, which are classified by young friends under the general name of gibberish, goes in New England by the name of "Hog Latin." It consists simply in the addition of the syllable ery, preceded by the sound of hard g, to every word. Even this is puzzling to older persons, who do not at first perceive that "Wiggery youggery goggery wiggery miggery" means only "Will you go with me!" Children sometimes use this device so perpetually that parents fear lest they may never recover the command of their native English. When it ceases to give pleasure, new dialects are devised. Certain young friends of ours[Pg 25] at first changed the termination thus—"Withus yoovus govus withus meevus?" which must be answered, "Ivus withus govus withus yoovus;" the language, seemingly, not admitting a direct affirmative. The next step was to make a more complicated system by prefixing a u (or oo) sound with a vowel suffix. Thus, "Will you go with me to lunch?" would be "Uwilla uoa ugoa uwitha umea utoa uluncha?" But this contrivance, adopted by all the children of a neighborhood,[25] was attended with variations incapable of reduction to rule, but dependent on practice and instinct. The speech could be learned, like any other, only by experience; and a little girl assured us that she could not comprehend a single word until, in the course of a month, she had learned it by ear. She added, in regard to a particular dialect, that it was much harder than French, and that her brother had to think a great deal when he used it. The application of euphonic rules was more or less arbitrary. Thus, understand would be uery-uinste. The following will answer for a specimen of a conversation between a child and a nurse who has learned the tongue: "Uery uisy uemy uity?" "Up-stairs, on the screen in your room." The child had asked, "Where is my hat?"

A group of children living near Boston invented the cat language, so called because its object was to admit of free intercourse with cats, to whom it was mostly talked, and by whom it was presumed to be comprehended. In this tongue the cat was naturally the chief subject of nomenclature; all feline positions were observed and named, and the language was rich in such epithets, as Arabic contains a vast number of expressions for lion. Euphonic changes were very arbitrary and various, differing for the same termination; but the adverbial ending ly was always osh; terribly, tirriblosh. A certain percentage of words were absolutely independent, or at least of obscure origin. The grammar tended to Chinese or infantine simplicity; ta represented any case of any personal pronoun. A proper name might vary in sound according to the euphonic requirement of the different Christian-names by which it was preceded. There were two dialects, one, however, stigmatized as provincial.

This invention of language must be very common, since other cases have fallen under our notice in which children have composed dictionaries of such.

It would be strange if children who exhibit so much inventive talent did not contrive new games; and we find accordingly that in many families [Pg 26]a great part of the amusements of the children are of their own devising. The earliest age of which the writer has authentic record of such ingenuity is two and a half years.

Considering the space which our Indian tribes occupy in the imagination of young Americans, it is remarkable that the red man has no place whatever in the familiar and authorized sports. On the other hand, savage life has often furnished material for individual and local amusements.

Near the country place of a family within our knowledge was a patch of brushwood containing about forty acres, and furnishing an admirable ground for savage warfare. Accordingly, a regular game was devised. The players were divided into Indians and hunters, the former uttering their war-cry in such dialect as youthful imagination regarded as aboriginal. The players laid ambushes for each other in the forest, and the game ended with the extermination of one party or the other. This warfare was regulated by strict rules, the presentation of a musket at a fixed distance being regarded as equivalent to death.

In a town of Massachusetts, some thirty years since, it was customary for the school-girls, during recess, to divide themselves into separate tribes. Shawls spread over tent-poles represented Indian lodges, and a girl always resorted to her allotted habitation. This was kept up for the whole summer, and carried out with such earnestness that girls belonging to hostile tribes, though otherwise perfectly good friends, would often not speak to each other for weeks, in or out of school.

In the same town was a community of "Friends," or "Quakers." It was the custom for children of these to play at meeting. Sitting about the room on a "First-day" gathering, one of them would be moved by the spirit, rise, and exhort in the sing-song tone common to the meeting-house. There was a regular formula for this amusement—a speech which the children had somewhere heard and found laughable: "My de-ar friends, I've been a thinking and a thinking and a thinking; I see the blinking and the winking; pennyroyal tea is very good for a cold."

A young lady of our acquaintance, as a child, invented a game of pursuit, which she called Spider and Fly. The Flies, sitting on the house-stairs, buzzed in and out of the door, where they were exposed to the surprise of the Spider. The children of the neighborhood still maintain the sport, which is almost the exact equivalent of a world-old game whose formula is given in our collection.

We need not go on to illustrate our thesis. But it remains true that[Pg 27] the great mass of the sports here presented are not merely old, but have existed in many countries, with formulas which have passed from generation to generation. How are we to reconcile this fact with the quick invention we ascribe to children?

The simple reason why the amusements of children are inherited is the same as the reason why language is inherited. It is the necessity of general currency, and the difficulty of obtaining it, which restricts the variation of one and of the other. If a sport is familiar only to one locality or one set of children, it passes away as soon as the youthful fancy of that region grows weary of it. Besides, the old games, which have prevailed and become familiar by a process of natural selection, are usually better adapted to children's taste than any new inventions can be; they are recommended by the quaintness of formulas which come from the remote past, and strike the young imagination as a sort of sacred law. From these causes, the same customs have survived for centuries through all changes of society, until the present age has involved all popular traditions, those of childhood as of maturity, in a general ruin.

Greek Anthology.

As the light-footed and devious fancy of childhood, within its assigned limits, easily outstrips the grave progress of mature years, so the obedience of children is far more scrupulous not to overstep the limits of the path. It is a provision of nature, in order to secure the preservation of the race, that each generation should begin with the unquestioning reception of the precepts of that which it follows. No deputy is so literal, no nurse so Rhadamanthine, as one child left in charge of another. The same precision appears in the conduct of sports. The formulas of play are as Scripture, of which no jot or tittle is to be repealed. Even the inconsequent rhymes of the nursery must be recited in the form in which they first became familiar; as many a mother has learned, who has found the versions familiar to her own infancy condemned as inaccurate, and who is herself sufficiently affected by superstition to feel a little shocked, as if a sacred canon had been irreligiously violated.

The life of the past never seems so comprehensible, and the historic interval never so insignificant, as when the conduct and demeanor of children are in question. Of all human relations, the most simple and permanent one is that of parent and child. The loyalty which makes a clansman account his own interests as trifling in comparison with those of his chieftain, or subjects consider their own prosperity as included in their sovereign's, belongs to a disappearing society; the affection of the sexes is dependent, for the form of its manifestation, on the varying [Pg 29]usages of nations; but the behavior of little children, and of their parents in reference to them, has undergone small change since the beginnings of history. Homer might have taken for his model the nursery of our own day, when, in the words of Achilles' rebuke to the grief of Patroclus, he places before us a Greek mother and her baby—

And the passage is almost too familiar to cite—

In the same manner, too, as the feelings and tastes of children have not been changed by time, they are little altered by civilization, so that similar usages may be acceptable both to the cultivated nations of Europe and to the simpler races on their borders.

It is natural, therefore, that the common toys of children should be world-old. The tombs of Attica exhibit dolls of classic or ante-classic time, of ivory or terra-cotta, the finer specimens with jointed arms or legs. Even in Greece, as it seems, these favorites of the nursery were often modelled in wax; they were called by a pet name, indicating that their owners stood to them in the relation of mamma to baby; they had their own wardrobes and housekeeping apparatus. The Temple of Olympian Zeus at Elis contained, says Pausanias, the little bed with which Hippodamia had played. But the usage goes much further back. Whoever has seen the wooden slats which served for the cheaper class of the dolls of ancient Egypt, in which a few marks pass for mouth, nose, and eyes, will have no difficulty in imagining that their possessors regarded them with maternal affection, since all the world knows that a little girl will lavish more tenderness on a stuffed figure than on a Paris doll, the return of affection being proportional to the outlay of imagination.

When Greek and Roman girls had reached an age supposed to be superior to such amusements, they were expected to offer their toys on the[Pg 30] altar of their patroness, to whatever goddess might belong that function, Athene or Artemis, Diana or Venus Libitina. If such an act of devotion was made at the age of seven years, as alleged, one can easily understand that many a child must have wept bitterly over the sacrifice. To this usage refers the charming quatrain, a version of which we have set as the motto of our chapter.

Children's rattles have from the most ancient times been an important article of nursery furniture. Hollow balls containing a loose pebble, which served this purpose, belong to the most ancient classic times. These "rattles," however, often had a more artistic form, lyre-shaped with a moving plectrum; or the name was used for little separate metallic figures—"charms," as we now say—strung together so as to jingle, and worn in a necklace. Such were afterwards preserved with great care; in the comic drama they replace the "strawberry mark" by which the father recognizes his long-lost child. Thus, in the "Rudens" of Plautus, Palæstra, who has lost in shipwreck her casket, finds a fisherman in possession of it, and claims her property. Both agree to accept Dæmones, the unknown father of the maiden, as arbiter. Dæmones demands, "Stand off, girl, and tell me, what is in the wallet?" "Playthings."[27] "Right, I see them; what do they look like?" "First, a little golden sword with letters on it." "Tell me, what are the letters?" "My father's name. Then there is a two-edged axe, also of gold, and lettered; my mother's name is on the axe.... Then a silver sickle, and two clasped hands, and a little pig, and a golden heart, which my father gave me on my birthday." "It is she; I can no longer keep myself from embracing her. Hail, my daughter!"

In the ancient North, too, children played with figures of animals. The six-year-old Arngrim is described in a saga as generously making a present of his little brass horse to his younger brother Steinolf; it was more suitable to the latter's age, he thought.

The weapons of boys still preserve the memory of those used by primitive man. The bow and arrow, the sling, the air-gun, the yet more primeval club or stone, are skilfully handled by them. Their use of the top and ball has varied but little from the Christian era to the present day. It is, therefore, not surprising that many games are nearly the same as when Pollux described them in the second century.[28] Yet it interests us to discover that not only the sports themselves, but also the words of [Pg 31]the formulas by which they are conducted, are in certain cases older than the days of Plato and Xenophon.[29]

We have already set forth the history contained in certain appellations of the song and dance. If the very name of the chorus has survived in Europe to the present day, so the character of the classic round is perpetuated in the ring games of modern children. Only in a single instance, but that a most curious one, have the words of a Greek children's round been preserved. This is the "tortoise-game," given by Pollux, and we will let his words speak for themselves:

"The tortoise is a girl's game, like the pot; one sits, and is called tortoise. The rest go about asking:

She answers:

The first again:

To which she says:

Our author does not tell us how the game ended; but from his comparison to the "pot-game"[30] we conclude that the tortoise immediately dives into the "ocean" (the ring) to catch whom she can.

This quaint description shows us that the game-formulas of ancient times were to the full as incoherent and obscure as those of our day frequently are. The alliterative name of the tortoise,[31] too, reminding us of the repetitions of modern nursery tales, speaks volumes for the character of Greek childish song.

Kissing games, also, were as familiar in the classic period as in later time; for Pollux quotes the Athenian comic poet Crates as saying of a coquette that she "plays kissing games in rings of boys, preferring the handsome ones."

It must be confessed, however, that we can offer nothing so graceful [Pg 32]as the cry with which Greek girls challenged each other to the race, an exclamation which we may render, "Now, fairies!"[32]—the maidens assuming for the nonce the character of the light-footed nymphs of forest or stream.

Coming down to mediæval time, we find that the poets constantly refer to the life of children, with which they have the deepest sympathy, and which they invest with a bright poetry, putting later writers to shame by comparison. That early period, in its frank enjoyment of life, was not far from the spirit of childhood. Wolfram of Eschenbach represents a little girl as praising her favorite doll:

The German proverb still is "Happy as a doll."

It has been remarked how, in all times, the different sex and destiny of boys and girls are unconsciously expressed in the choice and conduct of their pleasures. "Women," says a writer of the seventeenth century, "have an especial fondness for children. That is seen in little girls, who, though they know not so much as that they are maids, yet in their childish games carry about dolls made of rags, rock them, cradle them, and care for them; while boys build houses, ride on a hobby-horse, busy themselves with making swords and erecting altars."

Like causes have occasioned the simultaneous disappearance of like usages in countries widely separated. In the last generation children still sang in our own towns the ancient summons to the evening sports—

and similarly in Provence, the girls who conducted their ring-dances in the public squares, at the stroke of ten sang:

But the usage has departed in the quiet cities of Southern France, as in the busy marts of America.

It is much, however, to have the pleasant memory of the ancient rules which youth established to direct its own amusement, and to know that [Pg 33]our own land, new as by comparison it is, has its legitimate share in the lore of childhood, in considering which we overleap the barriers of time, and are placed in communion with the happy infancy of all ages. Let us illustrate our point, and end these prefatory remarks, with a version of the description of his own youth given by a poet of half a thousand years since—no mean singer, though famous in another field of letters—the chronicler Jean Froissart. He regards all the careless pleasures of infancy as part of the unconscious education of the heart, and the thoughtless joy of childhood as the basis of the happiness of maturity; a deep and true conception, which we have nowhere seen so exquisitely developed, and which he illuminates with a ray of that genuine genius which remains always modern in its universal appropriateness, when, recounting the sports of his own early life,[33] many of which we recognize as still familiar, he writes:

[1] Boston.

[2] See Nos. 40 and 58.

[3] See No. 21.

[4] See No. 2.

[5] See No. 1.

[6] More than three fourths of all children's games in the German collections are paralleled (it may be in widely varying forms) in the present volume. Allowing for the incompleteness of collections, the resemblance of French games is probably nearly as close. The case is not very different in Italy and Sweden, so far at least as concerns games of any dramatic interest. Not till we come to Russia, do we find anything like an independent usage. Taken altogether, our American games are as ancient and characteristic as any, and throw much light on the European system of childish tradition.

[7] See Nos. 150-153.

[8] Barley-break. See No. 101.

[9] No. 90.

[10] It must be remembered that in mediæval Europe, and in England till the end of the seventeenth century, a kiss was the usual salutation of a lady to a gentleman whom she wished to honor. The Portuguese ladies who came to England with the Infanta in 1662 were not used to the custom; but, as Pepys says, in ten days they had "learnt to kiss and look freely up and down." Kissing in games was, therefore, a matter of course, in all ranks.

[11] Mme. Élisabeth-Félicie Bayle-Mouillard, who wrote under this pseudonym, had in her day a great reputation as a writer on etiquette. Her "Manuel Complet de la Bonne Compagnie" reached six editions in the course of a few years, and was published in America in two different translations—at Boston in 1833, and Philadelphia in 1841.

[12] See Nos. 10 and 36.

[13] See No. 154, and note.

[14] Ballad, ballet, ball, from ballare, to dance.

[15] See Nos. 12-17.

[16] Yet there is no modern English treatise on the history of the ballad possessing critical pretensions. It is to the unselfish labors of an American—Professor Francis J. Child, of Harvard University—that we are soon to owe a complete and comparative edition of English ballads.

[17] In the country, in Massachusetts, Thanksgiving evening was the particular occasion for these games.

[18] The feast of Flora, says Pliny, in order that everything should flower.

[19] So in Southern France—

[20] "On May-day eve, young men and women still continue to play each other tricks by placing branches of trees, shrubs, or flowers under each other's windows, or before their doors."—Harland, "Lancashire Folk-lore."

[21] The "Shepheards Calender" recites how, in the month of May,

"Sops in wine" are said to be pinks.

[22] See Nos. 23, 26, and 160.

[23] "In summer season howe doe the moste part of our yong men and maydes in earely rising and getting themselves into the fieldes at dauncing! What foolishe toyes shall not a man see among them!"—"Northbrooke's Treatise," 1577.

—Wm. Browne.

[25] In Cincinnati.

[26] The same Greek word, kora, signifies maiden and doll.

[27] Crepundia; literally, rattles.

[28] See Nos. 105 and 108.

[29] See Nos. 91, 92, and 93.

[30] "The pot-game—the one in the middle sits, and is called a pot; the rest tweak him, or pinch him, or slap him while running round; and whoever is caught by him while so turning takes his place." We might suppose the disconnected verse of the "tortoise-game" to be imitated, perhaps in jest, from the high-sounding phrases of the drama.

[31] "Cheli-chelone," torti-tortoise.

[32] "Phitta Meliades."

[33] Froissart's account of the school he attended reminds us of the American district school, and his narration has the same character of charming simplicity as his allusion to playing with the boys of our street.

[34] For the games here mentioned, compare note in Appendix.

GAMES AND SONGS OF AMERICAN CHILDREN

The Romaunt of the Rose.