The Project Gutenberg EBook of Roland Cashel, by Charles James Lever

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Roland Cashel

Volume II (of II)

Author: Charles James Lever

Illustrator: Phiz.

Release Date: August 19, 2010 [EBook #33469]

Last Updated: September 3, 2016

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ROLAND CASHEL ***

Produced by David Widger

CONTENTS

ROLAND CASHEL

CHAPTER I. AN “UNLIMITED” MONARCHY

CHAPTER II. LADY KILGOFF AT BAY

CHAPTER III. A PARTIAL RECOVERY AND A RELAPSE

CHAPTER IV. MORE KENNYFECK INTRIGUING

CHAPTER V. LINTON’S MYSTERIOUS DISAPPEARANCE

CHAPTER VI. THE SEASON OF LINTON’S FLITTING

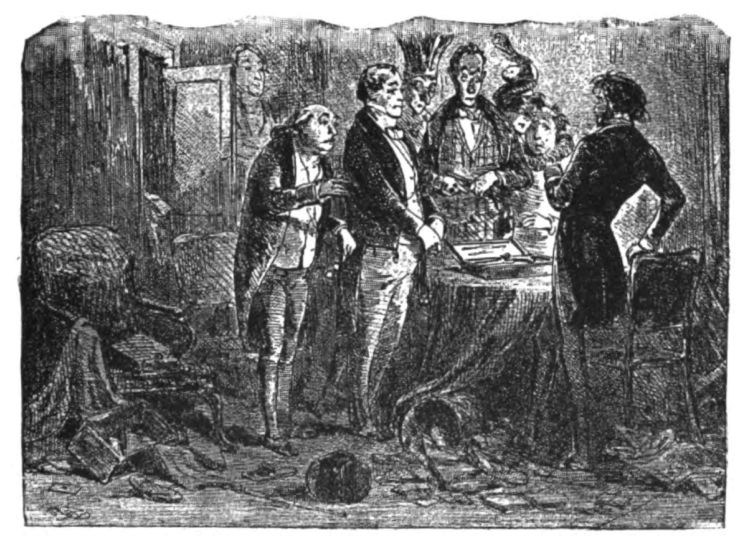

CHAPTER VII. FORGERY

CHAPTER VIII. ROLAND DISCOVERS THAT HE HAS OVERDRAWN

CHAPTER IX. THE BURNT LETTER—“GREAT EXPECTATIONS”

CHAPTER X. A STARTLING INTRUSION

CHAPTER XI. SCANDAL, AND GENERAL ILL-HUMOR

CHAPTER XII. SHYLOCK DEMANDS HIS BOND

CHAPTER XIII. CIGARS, ÉCARTÉ, AND HAZARD

CHAPTER XIV. MR. KENNYFECK AMONG THE BULLS

CHAPTER XV. POLITICAL ASPIRATIONS

CHAPTER XVI. A WET DAT—THE FALSE SIGNAL

CHAPTER XVII. THE SHADOW IN THE MIRROR

CHAPTER XVIII. THE OLD FRIENDS IN COUNCIL

CHAPTER XIX. A TÊTE-À-TÊTE INTERRUPTED

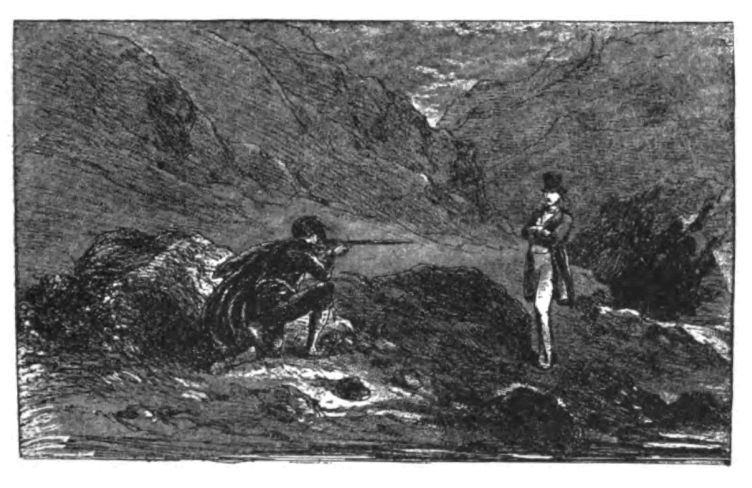

CHAPTER XX. LORD KILGOFF DETERMINES TO “MEET” ROLAND

CHAPTER XXI. THE SECOND SHOCK

CHAPTER XXII. LINTON INSTIGATES KEANE TO MURDER

CHAPTER XXIII. LINTON IS BAFFLED—HIS RAGE AT THE DISCOVERY

CHAPTER XXIV. GIOVANNI UNMASKED

CHAPTER XXV. TIERNAY INTIMIDATED——THE ABSTRACTED DEEDS

CHAPTER XXVI. AN UNDERSTANDING BETWEEN THE DUPE AND HIS VICTIM

CHAPTER XXVII. MURDER OF MR. KENNYFECK— CASHEL DETAINED ON SUSPICION

CHAPTER XXVIII. SCENE OF THE MURDER—THE CORONER’S VERDICT

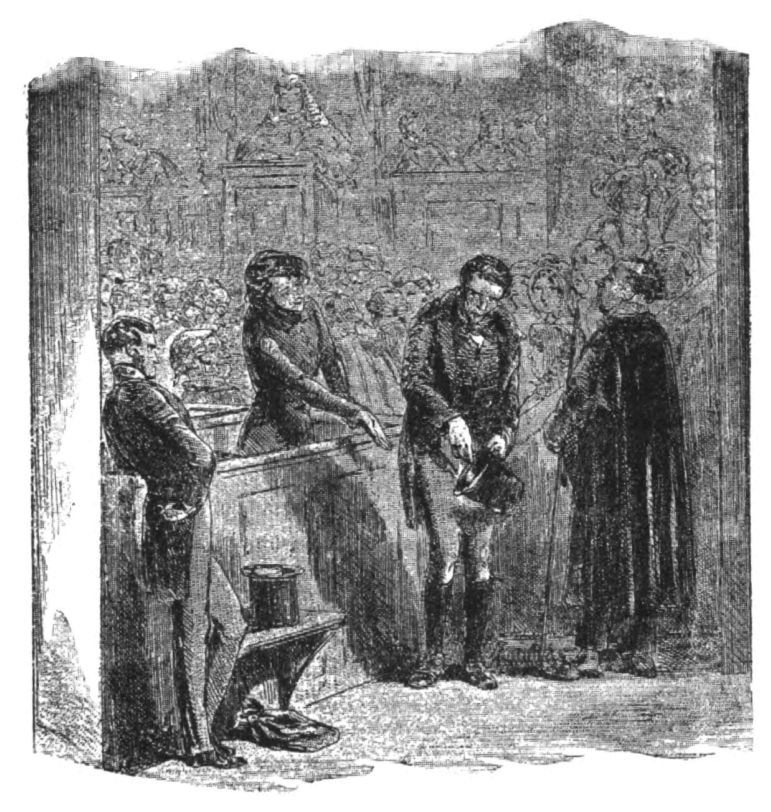

CHAPTER XXIX. THE TRIAL—THE PROSECUTION

CHAPTER XXX. THE DEFENCE

CHAPTER XXXI. "NOT GUILTY”

CHAPTER XXXII. ON THE TRACK

CHAPTER XXXIII. LA NINETTA

CHAPTER XXXIV. THE FATE OF KEANE—HIS DEPOSITION

CHAPTER XXXV. THE “BANK OF ROUGE ET NOIR”

CHAPTER XXXVI. ARREST OF LINTON

CHAPTER XXXVII. ALL MYSTERY CEASES—MARRIAGE AND GENERAL JOY

And at last they find out, to their greatest surprise, That’t is easier far to be “merry than wise.” Bell: Images.

“Here is Mr. Cashel; here he is!” exclaimed a number of voices, as Roland, with a heart full of indignant anger, ascended the terrace upon which the great drawing-room opened, and at every window of which stood groups of his gay company. Cashel looked up, and beheld the crowd of pleased faces wreathed into smiles of gracious welcome, and then he suddenly remembered that it was he who had invited all that brilliant assemblage; that, for him, all those winning graces were assumed; and that his gloomy thoughts, and gloomier looks, were but a sorry reception to offer them.

With a bold effort, then, to shake off the load that oppressed him, he approached one of the windows, where Mrs. Kennyfeck and her two daughters were standing, with a considerable sprinkling of young dragoons around them.

“We are not to let you in, Mr. Cashel,” said Mrs. Kennyfeck, from within. “There has been a vote of the House against your admission.”

“Not, surely, to condemn me unheard,” said Roland; “I might even say, unaccused.”

“How so?” cried Mrs. Kennyfeck. “Is not your present position your accusation? Why are you there, while we are here?”

“I went out for a walk, and lost myself in the woods.”

“What does he say, my dear?” said Aunt Fanny, fearful of losing a word of the dialogue.

“That he lost himself, madam,” said one of the dragoons, dryly.

“So, indeed, we heard, sir,” said the maiden lady, piteously; “but I may say I foresaw it all.”

“You are an old fool, and, worse still, every one sees it,” whispered Mrs. Kennyfeck, in an accent that there was no mistaking, although only a whisper.

“We considered that you had abdicated, Mr. Cashel,” said Mrs. White, who, having in vain waited for Roland to approach the window she occupied, was fain at last to join the others, “and we were debating on what form of Government to adopt,—a Presidency, with Mr. Linton—”

“I see you are no legitimist,” slyly remarked Miss Kenny-feck. But the other went on,—

“Or an open Democracy.”

“I ‘m for that,” said a jolly-looking cavalry captain. “Pray, Miss Olivia Kennyfeck, vote for it too. I should like nothing so much as a little fraternizing.”

“I have a better suggestion than either,” said Roland, gayly; “but you must admit me ere I make it.”

“A device of the enemy,” called out Mrs. White; “he wants to secure his own return to power.”

“Nay, on honor,” said he, solemnly; “I shall descend to the rank of the humblest citizen, if my advice be acceded to,—to the humblest subject of the realm.”

“Ye maunna open the window. Leddy Janet has the rheumatics a’ dandering aboot her back a’ the morning,” said Sir Andrew, approaching the group; and then, turning to Cashel, said, “Glad to see ye, sir; very glad indeed; though, like Prince Charlie, you’re on the wrang side o’ the wa’.”

“Dear me!” sighed Meek, lifting his eyes from the newspaper, and assuming that softly compassionate tone in which he always delivered the most commonplace sentiments, “how shocking, to keep you out of your own house, and the air quite damp! Do pray be careful, and change your clothes before you come in here.” Then he finished in a whisper to Lady Janet, “One never gets through a country visit without a cold.”

“Upon my word, I’ll let him in,” said Aunt Fanny, with a native richness of accent that made her fair nieces blush.

“At last!” said Cashel, as he entered the room, and proceeded to salute the company, with many of whom he had but the very slightest acquaintance,—of some he did not even remember the names.

The genial warmth of his character soon compelled him to feel heartily what he had begun by feigning, and he bade them welcome with a cordiality that spread its kindly influence over all.

“I see,” said he, after some minutes, “Lady Kilgoff has not joined us; but her fatigue has been very great.”

“They say my Lord ‘s clean daft,” said Sir Andrew.

“Oh, no, Sir Andrew,” rejoined Roland; “our misfortune has shaken his nerves a good deal, but a few days’ rest and quiet will restore him.”

“He was na ower wise at the best, puir man,” sighed the veteran, as he moved away.

“Her Ladyship was quite a heroine,—is n’t that so?” said Lady Janet, tartly.

“She held the rudder, or did something with the compass, I heard,” simpered a young lady in long flaxen ringlets.

Cashel smiled, but made no answer.

“Oh, dear,” sighed Meek, “and there was a dog that swam—or was it you that swam ashore with a rope in your mouth?”

“I grieve to say, neither man nor dog performed the achievement.”

“And it would appear that the horrid wretch—what’s his name?” asked Mrs. White of her friend Howie.

“Whose name, madam?”

“The man—the dreadful man, who planned it all. Sick—Sickamore—no, not Sickamore—”

“Sickleton, perhaps,” said Cashel, strangely puzzled to make out what was coming.

“Yes, Sickleton had actually done the very same thing twice before, just to get possession of the rich plate and all the things on board.”

“This is too bad,” cried Cashel, indignantly; “really, madam, you must pardon my warmth, if it even verges on rudeness; but the gentleman whose name you have associated with such iniquitous suspicions saved all our lives.”

“That’s what I like in him better than all,” whispered Aunt Fanny to Olivia; “he stands by his friends like a trump.”

“You have compelled me,” resumed Cashel, “to speak of what really I had much rather forget; but I shall insist upon your patience now for a few minutes, simply to rectify any error which may prevail upon this affair.”

With this brief prelude, Cashel commenced a narrative of the voyage from the evening of the departure from Kingstown to the moment of the vessel’s sinking off the south coast.

If most of his auditors only listened as to an interesting anecdote, to others the story had a deeper meaning. The Kennyfecks were longing to learn how the excursion originated, and whether Lady Kilgoff’s presence had been a pre-arranged plan, or a mere accidental occurrence.

“All’s not lost yet, Livy,” whispered Miss Kennyfeck in her sister’s ear. “I give you joy.” While a significant nod from Aunt Fanny seemed to divine the sentiment and agree with it.

“And I suppose ye had na the vessel insured?” said Sir Andrew, at the close of the narrative; “what a sair thing to think o’!”

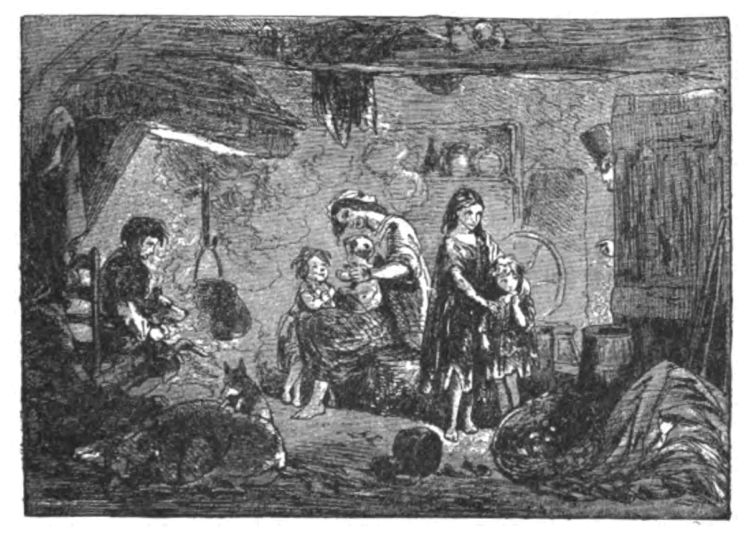

“Oh, dear, yes, to be sure!” ejaculated Meek, piteously; “and the cold, and the wetting, and the rest of it! for of course you must have met few comforts in that miserable fishing-hut.”

“How picturesque it must have been,” interposed Mrs. White; “and what a pity you had no means of having a drawing made of it. The scene at the moment of the yacht striking; the despair-struck seamen—”

“Pardon me, madam, for destroying even a particle of so ingenious a fancy; but the men evinced nothing of the kind,—they behaved well, and with the calmest steadiness.”

“It is scarcely too late yet,” resumed the lady, unabashed; “if you would just describe it all carefully to Mr. Howie, he could made a sketch in oils one would swear was taken on the spot.”

“Quite impossible,—out of the question,” said Howie, who was always ashamed at the absurdities which compromised himself, although keenly alive to those which involved his neighbors.

“We have heard much of Lady Kilgoff’s courage and presence of mind,” said Mrs. Kennyfeck, returning to a theme by which she calculated on exploring into Cashel’s sentiments towards that lady. “Were they indeed so conspicuous?”

“Can you doubt it, madam?” said Lady Janet, tartly; “she gave the most unequivocal proof of both,—she remembered her husband!”

The tartness of this impertinent speech was infinitely increased by the voice and manner of the speaker, and a half-suppressed titter ran through the room, Cashel alone, of all, feeling annoyed and angry. Aunt Fanny, always less occupied with herself than her neighbors, quickly saw his irritation, and resolved to change a topic which more than once had verged on danger.

“And now, Mr. Cashel,” said she, “let us not forget the pledge on which we admitted you.”

“Quite right,” exclaimed Roland; “I promised a suggestion: here it is—”

“Pardon me for interrupting,” said Miss Kennyfeck; “but in what capacity do you make this suggestion? Are you still king, or have you abdicated?”

“Abdicated in all form,” replied Roland, bowing with well-assumed humility; “as simple citizen, I propose that we elect a ‘Queen,’ to rule despotically in all things,—uncontrolled and irresponsible.”

“Oh, delightful! admirable!” exclaimed a number of voices, among which all the men and the younger ladies might be heard; Lady Janet and Mrs. Kennyfeck, and a few others “of the senior service,” as Mr. Linton would have called them, seeming to canvass the motion with more cautious reserve.

“As it is to be an elective monarchy, sir,” said Lady Janet, with a shrewd glance over all the possible candidates, “how do you propose the choice is to be made?”

“That is to be for after consideration,” replied Roland; “we may have universal suffrage and the ballot.”

“No, no, by Jove!” exclaimed Sir Harvey Upton; “we must not enter upon our new reign by a rebellion. Let only the men vote.”

“How gallant!” said Miss Kennyfeck, sneeringly; while a chorus of “How unfair!” “How ungenerous!” went through the room.

“What say ye to the plan they hae wi’ the Pope?” said Sir Andrew, grinning maliciously: “tak’ the auldest o’ the company.”

This suggestion caused a laugh, in which certain parties did not join over-heartily. Just at this moment the door opened, and Lord Kilgoff, leaning on the arm of two servants, entered. He was deathly pale, and seemed several years older; but his face had acquired something of its wonted expression, and it was with a sad but courteous smile he returned the salutations of the company.

“Glad to see you amongst us, my Lord,” said Cashel, as he placed an arm-chair, and assisted the old man to his seat. “I have just been telling my friends that our country air and quiet will speedily restore you.”

“Thank you very much, sir,” said he, taking Cashel’s hand. “We are both greatly indebted to your kindness, nor can we indeed ever hope to repay it.”

“Make him a receiver on the estate, then,” whispered Lady Janet in Miss Kennyfeck’s ear, “and he’ll soon pay himself.”

“Tell my Lord about our newly intended government, Mr. Cashel,” said Mrs. Kennyfeck; “I’m sure it will amuse him.” And Cashel, more in obedience to the request than from any conviction of its prudence, proceeded to obey. One word only, however, seemed to fix itself on the old man’s memory.

“Queen! queen!” repeated he several times to himself. “Oh, indeed! You expect her Majesty will honor you with a visit, sir?”

Cashel endeavored to correct the misconception, but to no purpose; the feeble intelligence could not relinquish its grasp so easily, and he went on in a low muttering tone,—

“Lady Kilgoff is the only peeress here, sir, remember that; you should speak to her about it, Mr. Cashel.”

“I hope we are soon to have the pleasure of seeing Lady Kilgoff, my Lord,” whispered Cashel, half to concur with, half to turn the course of conversation.

“She will be here presently,” said he, somewhat stiffly, as if some unpleasant recollection was passing through his mind; and Cashel turned away to speak with the others, who eagerly awaited to resume the interrupted conversation.

“Your plan, Mr. Cashel; we are dying to hear it,” cried one.

“Oh, by all means; how are we to elect the queen?” said another.

“What say you to a lottery,” said he, “or something equally the upshot of chance? For instance, let the first lady who enters the room be queen.”

“Very good indeed,” said Lady Janet, aloud; then added, in a whisper, “I see that old Mrs. Malone with her husband toddling up the avenue this instant.”

“Olivia, my love,” whispered Mrs. Kennyfeck to her daughter, “fetch me my work here, and don’t be a moment away, child. He’s so amusing!” And the young lady glided unseen from the room at her mamma’s bidding. After a short but animated conversation, it was decided that this mode of choice should be adopted; and now all stood in anxious expectancy to see who first should enter. At last footsteps were heard approaching, and the interest rose higher.

“Leddy Janet was right,” said Sir Andrew, with a grin; “ye ‘ll hae Mrs. Malone for your sovereign,—I ken her step weel.”

“By Jove!” cried Upton, “I ‘ll dispute the succession; that would never do.”

“That’s-a lighter tread and a faster,” said Cashel, listening.

“There are two coming,” cried Mrs. White; “I hear voices: how are we then to decide?”

There was no time to canvass this knotty point, when a hand was heard upon the door-handle; it turned, and just as the door moved, a sound of feet upon the terrace without,—running at full speed,—turned every eye in that direction, and the same instant Miss Meek sprang into the room through the window, while Lord Charles and Linton hurried after her, at the same moment that Lady Kilgoff, followed by Olivia Kennyfeck, entered by the door.

Miss Meek’s appearance might have astonished the company, had even her entrée been more ceremonious; for she was without hat, her hair falling in long, dishevelled masses about her shoulders, and her riding-habit, torn and ragged, was carried over one arm, with a freedom much more in accordance with speed than grace.

“Beat by two lengths, Charley,” cried she, in a joyous, merry laugh; “beat in a canter,—Mr. Linton, nowhere.”

“Oh, dear me, what is all this, Jemima love?” softly sighed her bland papa; “you’ve not been riding, I hope?”

“Schooling a bit with Charley, pa, and as we left the nags at the stable, they challenged me to a race home; I don’t think they’ll do it again. Do look how they’re blown.”

Some of the company laughed good-humoredly at the girlish gayety of the scene. Others, among whom, it is sad to say, were many of the younger ladies, made significant signs of being shocked by the indecorum, and gathered in groups to canvass the papa’s indifference and the daughter’s indelicacy. Meanwhile Cashel had been completely occupied with Lady Kilgoff, making the usual inquiries regarding fatigue and rest, but in a manner that bespoke all his interest in a favored guest.

“Are you aware to what high destiny the Fates have called you?” said he, laughing. “Some attain fortune by being first to seek her,—you, on the contrary, win by dallying. We had decided, a few moments before you came in, that the first lady who entered should be the Queen of our party,—this lot is yours.”

“I beg to correct you, Mr. Cashel,” cried Lady Janet, smartly; “Miss Meek entered before her Ladyship.”

“Oh, yes!” “Certainly!” “Without a doubt!” resounded from the whole company, who were not sorry to confer their suffrages on the madcap girl rather than the fashionable beauty.

“How distressing!” sighed Mr. Meek. “Oh, dear! I hope this is not so,—nay, I ‘m sure, Jemima, it cannot be the case.”

“You’re thinking of George Colman, Meek,—I see you are,” cried Linton.

“No, indeed; no, upon my honor. What was it about Colman?”

“The story is everybody’s story. The Prince insisted once that George was his senior, and George only corrected himself of his mistake by saying that ‘he could not possibly have had the rudeness to enter the world before his Royal Highness.’”

“Ah! yes—very true—so it was,” sighed Meek, who-affected not to perceive the covert sneer at his assumed courtesy.

While, therefore, the party gathered around Cashel, with eager assurance of Miss Meek’s precedence, Lady Kilgoff, rising, crossed the room to where that young lady was standing, and gracefully arranging her loose-flowing ringlets into a knot at the back of the head, fastened them by a splendid comb which she took from her own, and whose top was fashioned into a handsome coronet of gold, saying, “The question of legitimacy is solved forever: the Pretender yields her crown to the true Sovereign.”

The gracefulness and tact of this sudden movement called forth the warmest acknowledgments of all save Lady Janet, who whispered to Miss Kenny feck, “It is pretty clear, I fancy, who is to pay for the crown jewels!”

“Am I really the Queen?” cried the young girl, half wild with delight.

“Most assuredly, madam,” said Linton, kissing her hand in deep reverence. “I beg to be first to tender my homage.”

“That ‘s so like him!” cried she, laughing; “but you shall be no officer of mine. Where ‘s Charley? I want to make him Master of the Buckhounds, if there be buckhounds.”

“Will you not appoint your ladies first, madam?” said Lady Janet; “or, are your preferences for the other sex to leave us quite forgotten?”

“Be all of you everything you please,” rejoined the childish, merry voice, “with Charley Frobisher for Master of the Horse.”

“Linton for Master of the Revels,” said some one.

“Agreed,” said she.

“Mr. Cashel had better be First Lord of the Treasury, I suspect,” said Lady Janet, snappishly, “if the Administration is to last.”

“And if ye a’ways wear drapery o’ this fashion,” said Sir Andrew, taking up the torn fragment of her riding-habit as he spoke, “I maun say that the Mistress of the Robes will na be a sinecure.”

“Will any one tell me what are my powers?” said she, sitting down with an air of mock dignity.

“Will any one dare to say what they are not?” responded Cashel.

“Have I unlimited command in everything?”

“In everything, madam; I and all mine are at your orders.”

“That’s what the farce will end in,” whispered Lady Janet to Mrs. Kennyfeck.

“Well, then, to begin. The court will dine with us today—to-morrow we will hunt in our royal forest; our private band—Have we a private band, Mr. Linton?”

“Certainly, your Majesty,—so private as to be almost undiscoverable.”

“Then our private band will perform in the evening; perhaps, too, we shall dance. Remember, my Lords and Ladies, we are a young sovereign who loves pleasure, and that a sad face or a mournful one is treason to our person. Come forward now, and let us name our household.”

While the group gathered around the wild and high-spirited girl, in whose merry mood even the least-disposed were drawn to participate, Linton approached Lady Kilgoff, who had seated herself near a window, and was affecting to arrange a frame of embroidery, on which she rarely bestowed a moment’s labor.

I’ll make her brew the beverage herself, With her own fingers stir the cap, And know’t is poison as she drinks it. Harold.

Had Linton been about to renew an acquaintance with one he had scarcely known before, and who might possibly have ceased to remember him, his manner could not have been more studiously diffident and respectful.

“I rejoice to see your Ladyship here,” said he, in a low, deliberate voice, “where, on the last time we spoke together, you seemed uncertain of coming.”

“Very true, Mr. Linton,” said she, not looking up from her work; “my Lord had not fully made up his mind.”

“Say, rather, your Ladyship had changed yours,” said he, with a cold smile,—“a privilege you are not wont to deny yourself.”

“I might have exercised it oftener in life with advantage,” replied she, still holding her head bent over the embroidery frame.

“Don’t you think that your Ladyship and I are old friends enough to speak without innuendo?”

“If we speak at all,” said she, with a low but calm accent.

“True, that is to be thought of,” rejoined he, with an unmoved quietude of voice. “Being in a manner prepared for a change in your Ladyship’s sentiments towards me—”

“Sir!” said she, interrupting, and as suddenly raising her face, which was now covered with a deep blush.

“I trust I have said nothing to provoke reproof,” said Linton, coldly. “Your Ladyship is well aware if my words be not true. I repeat it, then,—your sentiments are changed towards me, or—the alteration is not of my choosing—I was deceived in the expression of them when last we met.”

“It may suit your purpose, sir, but it can scarcely conform to the generosity of a gentleman, to taunt me with acceding to your request for a meeting. If any other weakness can be alleged against me, pray let me hear it.”

“When we last met,” said Linton, in a voice of lower and deeper meaning than before, “we did so that I might speak, and you hear, the avowal of a passion which for years has filled my heart—against which I have struggled and fought in vain—to stifle which I have plunged into dissipations that I detested, and followed ambitions I despised—to obliterate all memory of which I would stoop to crime itself, rather than suffer on in the hopeless misery I must do.”

“I will hear no more of this,” said she, pushing back the work-table, and preparing to rise.

“You must and you shall hear me, madam,” said he, replacing the table and affecting to arrange it for her. “I conclude you do not wish this amiable company to arbitrate between us.”

“Oh, sir! is it thus you threaten me?”

“You should say compromise, madam. There can be no threat where a common ruin impends on all concerned.”

“To what end all this, Mr. Linton?” said she. “You surely cannot expect from me any return to a feeling which, if it once existed, you yourself were the means of uprooting forever. Even you could scarcely be ungenerous enough to persecute one for whose misery you have done already too much.”

“Will you accept my arm for half an hour?” cried he, interrupting. “I pledge myself it shall be the last time I either make such a request, or even allude to this topic between us. On the pretence of showing you the house, I may be able—if not to justify myself—nay, I see how little you care for that—well, at least to assure you that I have no other wish, no other hope, than to see you happy.”

“I cannot trust you,” said she, in a tone of agitation; “already we are remarked.”

“So I perceive,” said he, in an undertone; then added, in a voice audible enough to be heard by the rest, “I am too vain of my architectural merits to leave their discovery to chance; and as you are good enough to say you would like to see the house, pray will your Ladyship accept my arm while I perform the cicerone on myself?”

The coup succeeded, and, to avoid the difficulty and embarrassment a refusal would have created, Lady Kilgoff arose, and prepared to accompany him.

“Eh, what—what is’t, my Lady?” said Lord Kilgoff, suddenly awaking from a kind of lethargic slumber, as she whispered some words in his ear.

“Her Ladyship is telling you not to be jealous, my Lord, while she is making the tour of the house with Mr. Linton,” said Lady Janet, with a malicious sparkle of her green eyes.

“Why not make it a royal progress?” said Sir Harvey. “Her Majesty the Queen might like it well.”

“Her Majesty likes everything that promises amusement,” said the wild romp; “come, Charley, give us your arm.

“No, I ‘ve got a letter or two to write,” said he, rudely; “there ‘s Upton or Jennings quite ready for any foolery.”

“This is too bad!” cried she; and through all the pantomime of mock royalty, a real tear rose to her eyes, and rolled heavily down her cheek; then, with a sudden change of humor, she said, “Mr. Cashel, will you take me?”

The request was too late, for already he had given his arm to Lady Janet,—an act of devotion he was performing with the expression of a saint under martyrdom.

“Sir Harvey,—there’s no help for it,—we are reduced to you.”

But Sir Harvey was leaving the room with Olivia Kenny-feck. In fact, couples paired off in every direction; the only disengaged cavalier being Sir Andrew MacFarline, who, with a sardonic grin on his features, came hobbling forward, as he said,—

“Te maunna tak sich long strides, Missy, if ye ga wf me, for I’ve got a couple o’ ounces of Langredge shot in my left knee—forbye the gout in both ankles.”

“I say, Jim,” called out Lord Charles, as she moved away, “if you like to ride Princepino this afternoon, he’s-ready for you.”

“Are you going?” said she, turning her head.

“Yes.”

“Then I’ll not go.” And so saying, she left the room.

When Linton, accompanied by Lady Kilgoff, issued from the drawing-room, instead of proceeding through the billiard-room towards the suite which formed the “show” part of the mansion, he turned abruptly to his left, and, passing through a narrow corridor, came out upon a terrace, at the end of which stood a large conservatory, opening into the garden.

“I ask pardon,” said he, “if I reverse the order of our geography, and show you the frontiers of the realm before we visit the capital; but otherwise we shall only be the advance-guard of that interesting company who have nothing more at heart than to overhear us.”

Lady Kilgoff walked along without speaking, at his side, having relinquished the support of his arm with a stiff, frigid courtesy. Had any one been there to mark the two-figures, as side by side they went, each deep in thought, and not even venturing a glance at the other, he might well have wondered what strange link could connect them. It was thus they entered the conservatory, where two rows of orange-trees formed a lane of foliage almost impenetrable to the eye.

“As this may be the last time we shall ever speak together in secret—”

“You have promised as much, sir,” said she, interrupting; and the very rapidity of her utterance betrayed the eagerness of her wish.

“Be it so, madam,” replied he, coldly, and with a tone of sternness very different from that he had used at first. “I have ever preferred your wishes to my own. I shall never prove false to that allegiance. As we are now about to speak on terms which never can be resumed, let us at least be frank. Let us use candor with each other. Even unpleasing truth is better at such a moment than smooth-tongued insincerity.”

“This preamble does not promise well,” said Lady Kilgoff, with a cold smile.

“Not, perhaps, for the agreeability of our interview, but it may save us both much time and much temper. I have said that you are changed towards me.”

“Oh, sir! if I had suspected that this was to be the theme—” She stopped, and seemed uncertain, when he finished the speech for her.

“You would never have accorded me this meeting. Do be frank, madam, and spare me the pain of self-inflicted severity. Well, I will not impose upon your kindness,—nor indeed was such my intention, if you had but heard me out. Yes, madam, I should have told you that while I deplore that alteration, I no more make you chargeable with it, than you can call me to account for cherishing a passion without a hope. Both one and the other are independent of us. That one should forget and the other remember is beyond mere volition.”

He waited for some token of assent, some slight evidence of concurrence; but none came, and he resumed:

“When first I had the happiness of being distinguished by some slight show of your preference, there were many others who sought with eagerness for that position I was supposed to occupy in your favor. It was the first access of vanity in my heart, and it cost me dearly. Some envied me; some scoffed; some predicted that my triumph would be a brief one; some were rude enough to say that I was only placed like a buoy, to show the passage, and that I should lie fast at anchor while others sailed on with prosperous gale and favoring fortune. You, madam, best know which of these were right. I see that I weary you. I can conceive how distasteful all these memories must be, nor should I evoke them without absolute necessity. To be brief, then, you are now about to play over with another the very game by which you once deceived me. It is your caprice to sacrifice another to your vanity; but know, madam, the liberties which the world smiled at in Miss Gardiner will be keenly criticised in the Lady Kilgoff. In the former case, the most malevolent could but hint at a mésalliance; in the latter, evil tongues can take a wider latitude. To be sure, the fascinating qualities of the suitor, his wealth, his enviable position, will plead with some; my Lord’s age and decrepitude will weigh with others: but even these charitable persons will not spare you. Your own sex are seldom over-merciful in their judgments. Men are unscrupulous enough to hint that there was no secret in the matter; some will go further, and affect to say that they themselves were not unfavorably looked on.”

“Will you give me a chair, sir?” said she, in a voice which, though barely above a whisper, vibrated with intense passion. Linton hastened to fetch a seat, his whole features glowing with the elation of his vengeance. This passed rapidly away, and as he placed the chair for her to sit down, his face had resumed its former cold, almost melancholy expression.

“I hope you are not ill?” said he, with an air of feeling.

A glance of the most ineffable scorn was her only reply.

“It is with sincere sorrow that I inflict this pain upon you,—indeed, when I heard of that unhappy yacht excursion, my mind was made up to see Lord Kilgoff the very moment of his arrival, and, on any pretence, to induce him to leave this. This hope, however, was taken from me, when I beheld the sad state into which he had fallen, leaving me no other alternative than to address yourself. I will not hurt your ears by repeating the inventions, each full of falsehood, that heralded your arrival here. The insulting discussions how you should be met—whether your conduct had already precluded your acceptance amongst the circle of your equals—or, that you were only a subject of avoidance to mothers of marriageable daughters, and maiden ladies of excessive virtue. You have mixed in the world, and therefore can well imagine every ingenious turn of this peculiar eloquence. How was I—I who have known—I who—nay, madam, not a word shall pass my lips in reference to that theme—I would only ask, Could I hear these things, could I see your foot nearing the cliff, and not cry out, Stop?—Another step, and you are lost! There are women who can play this dangerous game with cool heads and cooler hearts: schooled in all the frigid indifference that would seem the birthright of a certain class, the secrets of their affections die with them; but you are not one of these. Born in what they would call an humbler, but I should call a far higher sphere, where the feelings are fresher and the emotions purer, you might chance to—fall in love!”

A faint smile, so faint that it conveyed no expression to her eyes, was Lady Kilgoff’s acknowledgment of these last words.

“Have you finished, sir?” said she, as, after a pause of some seconds, he stood still.

“Not yet, madam,” replied he, dryly.

“In that case, sir, would it not be as well to tell the man who is lingering yonder to leave this? except, perhaps, it may be your desire to have a witness to your words.”

Linton started, and grew deadly pale; for he now perceived that the man must have been in the conservatory during the entire interview. Hastening round to where he stood, his fears were at once dispelled; for it was the Italian sailor, Giovanni, who, in the multiplicity of his accomplishments, was now assisting the gardener among the plants.

“It is of no consequence, madam,” said he, returning; “the man is an Italian, who understands nothing of English.”

“You are always fortunate, Mr. Linton,” said she, with a deep emphasis on the pronoun.

“I have ceased to boast of my good luck for many a day.”

“Having, doubtless, so many other qualities to be proud of,” said she, with a malicious sparkle of her dark eyes.

“The question is now, madam, of one far more interesting than me.”

“Can that be possible, sir? Is any one’s welfare of such moment to his friends—to the world at large—as the high-minded, the honorable, the open-hearted Mr. Linton, who condescends, for the sake of a warning to his young friends, to turn gambler and ruin them; while he has the daring courage to single out a poor unprotected woman, without one who could rightly defend her, and, under the miserable mask of interest, to insult her?”

“Is it thus you read my conduct, madam?” said he, with an air at once sad and reproachful.

“Not altogether, Mr. Linton. Besides the ineffable pleasure of giving pain, I perceive that you are acquitting a debt,—the debt of hate you owe me; because—But I cannot descend to occupy the same level with you in this business. My reply to you is a very short one. Your insult to me must go unpunished; for, as you well know, I have not one to resent it. You have, however, introduced another name in this discussion; to that gentleman I will reveal all that you have said this day. The consequences may be what they will, I care not; I never provoked them. You best know, sir, how the reckoning will fare with you.”

Linton grew pale, almost lividly so, while he bit his lip till the very blood came; then, suddenly recovering himself, he said: “I am not aware of having mentioned a name. I think your Ladyship must have been mistaken; but”—and here he laughed slightly—“you will scarce succeed in sowing discord between me and my old friend, Lord Charles Frobisher.”

“Lord Charles Frobisher!” echoed she, almost stunned with the effrontery.

“You seem surprised, madam. I trust your Ladyship meant no other.” The insolence of his manner, as he said this, left her unable for some minutes to reply, and when she did speak, it was with evident effort.

“I trust now, sir, that we have spoken for the last time together. I own—and it is, indeed, humiliation enough to own it—your words have deeply insulted me. I cannot deny you the satisfaction of knowing this; and yet, with all these things before me, I do not hate—I only despise you.”

So saying, she moved towards the door; but Linton stepped forward, and said: “One instant, madam. You seem to forget that we are pledged to walk through the rooms; our amiable friends are doubtless looking for us.”

“I will ask Mr. Cashel to be my chaperon another time,” said she, carelessly, and, drawing her shawl around her, passed out, leaving Linton alone in the conservatory.

“Ay, by St Paul! the work goes bravely on,” cried he, as soon as she had disappeared. “If she ruin not him and herself to boot, now, I am sore mistaken. The game is full of interest, and, if I had not so much in hand, would delight me.”

With this brief soliloquy, he turned to where the Italian was standing, pruning an orange-tree.

“Have you learned any English yet, Giovanni?”

A slight but significant gesture of one finger gave the negative.

“No matter, your own soft vowels are in more request here. The dress I told you of is now come,—my servant will give it to you; so, be ready with your guitar, if the ladies wish for it, this evening.”

Giovanni bowed respectfully, and went on with his work, and soon after Linton strolled into the garden to muse over the late scene.

Had any one been there to mark the signs of triumphant elation on his features, they would have seen the man in all the sincerity of his bold, bad heart. His success was perfect. Knowing well the proud nature of the young, high-spirited woman, thoroughly acquainted with her impatient temper and haughty character, he rightly foresaw that to tell her she had become the subject of a calumny was to rouse her pride to confront it openly. To whisper that the world would not admit of this or that, was to make her brave that world, or sink under the effort.

To sting her to such resistance was his wily game, and who knew better how to play it? The insinuated sneers at the class to which she had once belonged, as one not “patented” to assume the vices of their betters, was a deep and most telling hit; and he saw, when they separated, that her mind was made up, at any cost and every risk, to live down the slander by utter contempt of it Linton asked for no more. “Let her,” said he to himself, “but enter the lists with the world for an adversary! I ‘ll give her all the benefits of the best motives,—as much purity of heart, and so forth, as she cares for; but, ‘I ‘ll name the winner,’ after all.”

Too true. The worthy people who fancy that an innate honesty of purpose can compensate for all the breaches of conventional use, are like the volunteers of an army who refuse to wear its uniform, and are as often picked down by their allies as by their enemies.

Such a concourse ne’er was seen Of coaches, noddies, cars, and jingles, “Chars-a-bancs,” to hold sixteen, And “sulkies,” meant to carry singles. The Pic-nic: A Lay.

It is an old remark that nothing is so stupid as love-letters; and, pretty much in the same spirit, we may affirm that there are few duller topics than festivities. The scenes in which the actor is most interested are, out of compensation, perhaps, those least worthy to record; the very inability of description to render them is disheartening too. One must eternally resort to the effects produced, as evidences of the cause, just as, when we would characterize a climate, we find ourselves obliged to fall back upon the vegetable productions, the fruits and flowers of the seasons, to convey even anything of what we desire. So is it Pleasure has its own atmosphere,—we may breathe, but hardly chronicle it.

These prosings of ours have reference to the gayeties of Tubbermore, which certainly were all that a merry party and an unbounded expenditure could compass. The style of living was princely in its splendor; luxuries fetched from every land,—the rarest wines of every country, the most exquisite flowers,—all that taste can suggest, and gold can buy, were there; and while the order of each day was maintained with undiminished splendor, every little fancy of the guests was studied with a watchful politeness that marks the highest delicacy of hospitality.

If a bachelor’s house be wanting in the gracefulness which is the charm of a family reception, there is a freedom, a degree of liberty in all the movements of the guests, which some would accept as a fair compromise; for, while the men assume a full equality With their host, the ladies are supreme in all such establishments. Roland Cashel was, indeed, not the man to dislike this kind of democracy; it spared him trouble; it inflicted no tiresome routine of attentions; he was free as the others to follow the bent of his humor, and he asked for no more.

It was without one particle of vulgar pride of wealth that he delighted in the pleasure he saw around him; it was the mere buoyancy of a high-spirited nature. The cost no more entered into his calculations in a personal than a pecuniary sense. A consciousness that he was the source of all that splendid festivity,—that his will was the motive-power of all that complex machinery of pleasure,—increased, but did not constitute, his enjoyment. To see his guests happy, in the various modes they preferred, was his great delight, and, for once, he felt inclined to think that wealth had great privileges.

The display of all which gratified him most was that which usually took place each day after luncheon; when the great space before the house was thronged with equipages of various kinds and degrees, with saddle-horses and mounted grooms, and amid all the bustle of discussing where to, and with whom, the party issued forth to spend the hours before dinner.

A looker-on would have been amused to watch all the little devices in request, to join this party, to avoid that, to secure a seat in a certain carriage, or to escape from some other; Linton’s chief amusement being to thwart as many of these plans as he could, and while he packed a sleepy Chief Justice into the same barouche with the gay Kennyfeck girls, to commit Lady Janet to the care of some dashing dragoon, who did not dare decline the wife of a “Commander of the Forces.”

Cashel always joined the party on horseback, so long as Lady Kilgoff kept the house, which she did for the first week of her stay; but when she announced her intention of driving out, he offered his services to accompany her. By the merest accident it chanced that the very day she fixed on for her first excursion was that on which Cashel had determined to try a new and most splendid equipage which had just arrived; it was a phaeton, built in all the costly splendor of the “Regency of the Duke of Orleans,”—one of those gorgeous toys which even a voluptuous age gazed at with wonder. Two jet-black Arabians, of perfect symmetry, drew it, the whole forming a most beautiful equipage.

Exclamations of astonishment and admiration broke from the whole party as the carriage drove up to the door, where all were now standing.

“Whose can it be? Where did it come from? What a magnificent phaeton! Mr. Cashel, pray tell us all about it. Do, Mr. Linton, give us its history.”

“It has none as yet, my dear Mrs. White; that it may have, one of these days, is quite possible.”

Lady Janet heard the speech, and nodded significantly in assent.

“Mr. Linton, you are coming with us, a’n’t you?” said a lady’s voice from a britzska close by.

“I really don’t know how the arrangement is; Cashel said something about my driving Lady Kilgoff.”

Lady Kilgoff pressed her lips close, and gathered her mantle together as if by some sudden impulse of temper, but never spoke a word. At the same instant Cashel made his appearance from the house.

“Are you to drive me, Mr. Cashel?” said she, calmly.

“If you will honor me so far,” replied he, bowing.

“I fancied you said something to me about being her Ladyship’s charioteer,” said Linton.

“You must have been dreaming, man,” cried Cashel, laughing.

“Will you allow my Lady to choose?” rejoined Linton, jokingly, while he stole at her a look of insolent malice.

Cashel stood uncertain what to say or do in the emergency, when, with a firm and determined voice, Lady Kilgoff said,—

“I must own I have no confidence in Mr. Linton’s guidance.”

“There, Tom,” said Cashel, gayly, “I ‘m glad your vanity came in for that.”

“I have only to hope that you are in safer conduct, my Lady,” said Linton; and he bowed with uncovered head, and then stood gazing after the swift carriage as it hastened down the avenue.

“Is it all true about these Kennyfeck girls having so much tin’?” said Captain Jennings, as he stroked down his moustache complacently.

“They say five-and-twenty thousand each,” said Linton, “and I rather credit the rumor.”

“Eh, aw! one might do worse,” yawned the hussar, languidly; “I wish they hadn’t that confounded accent!” And so he moved off to join the party on horseback.

“You are coming with me, Jemima,” said Mr. Downie Meek to his daughter. “I want to pay a visit to those works at Killaloe, we have so much committee talk in the House on inland navigation. Oh, dear! it is very tiresome.”

“Charley says I ‘m to go with him, pa; he ‘s about to try Smasher as a leader, and wants me, if anything goes wrong.”

“Oh, dear! quite impossible.”

“Yes, yes, Jim, I insist,” said Frobisher, in a half-whisper; “never mind the governor.”

“Here comes the drag, pa. Oh, how beautiful it looks! There they go, all together; and Smasher, how neatly he carries himself! I say, Charley, he has no fancy for that splinter-bar so near him,—it touches his near hock every instant; would n’t it be better to let his trace a hole looser?”

“So it would,” said Frobisher; “but get up and hold the ribbons till I have got my gloves on. I say, Linton, keep Downie in chat one moment, until we ‘re off.”

This kindly office was, however, anticipated by Lady Janet MacFarline, who, in her brief transit from the door to the carriage, always contrived to drop each of the twenty things she loaded herself with at starting, and thus to press into the service as many of the bystanders as possible, who followed, one with a muff, another with a smelling-bottle, a third with a book, a fourth with her knitting, and so on; while Flint brought up the rear with more air-cushions and hot-water apparatus than ever were seen before for the accommodation of two persons. In fact, if the atmosphere of our dear island, instead of being the mere innocent thing of fog it is, had been surcharged with all the pestilential vapors of the mistral and the typhoon together, she could not have armed herself with stronger precautions against it; while even Sir Andrew, with the constitution of a Russian bear, was compelled to wear blue spectacles in sunshine, and a respirator when it lowered,—leaving him, as he said, to the “domnable alternative o’ being blind or dumb.”

“I maun say,” muttered he, behind his barrier of mouth plate, “that Mesther Cashel has his ain notions aboot amusin’ his company when he leaves ane o’ his guests to drive aboot wi’ his ain wife. Ech, sir, it is a pleasure I need na hae come so far to enjoy.”

“Where’s Sir Harvey Upton, Sir Andrew?” said my Lady, tartly; “he has never been near me to-day. I hope he ‘s not making a fool of himself with those Kennyfeck minxes.”

“I dinna ken, and I dinna care,” growled Sir Andrew; and then to himself, he added, “An’ if he be, it’s aye better fooling wi’ young lassies than doited auld women!”

“A place for you, Mr. Linton!” said Mrs. White, as she seated herself in a low drosky, where her companion, Mr. Howie, sat, surrounded with all the details for a sketching-excursion.

“Thanks, but I have nothing so agreeable in prospect.”

“Why, what are you about to do?”

“Alas! I must set out on a canvassing expedition, to court the sweet voices of my interesting constituency. You know that I am a candidate for the borough.”

“That must be very disagreeable.”

“It is, but I could not get off; Cashel is incurably lazy, and I never know how to say ‘no.’”

“Well, good-bye, and all fortune to you,” said she; and they drove away.

Mr. Kennyfeck and the Chief Justice, mounted on what are called sure-footed ponies, and a few others, still lingered about the door, but Linton took no notice of them, but at once re-entered the house.

For some time previous he had remarked that Lord Kilgoff seemed, as it were, struggling to emerge from the mist that had shrouded his faculties; his perceptions each day grew quicker and clearer, and even when silent, Linton observed that a shrewd expression of the eye would betoken a degree of apprehension few would have given him credit for. With the keenness of a close observer, too, Linton perceived that he more than once made use of his favorite expression, “It appears to me,” and slight as the remark might seem, there is no more certain evidence of the return to thought and reason than the resumption of any habitual mode of expression.

Resolved to profit by this gleam of coming intelligence, by showing the old peer an attention he knew would be acceptable, Linton sent up a message to ask “If his Lordship would like a visit from him?” A most cordial acceptance was returned; and, a few moments after, Linton entered the room where he sat, with all that delicate caution so becoming a sick chamber.

Motioning his visitor to sit down, by a slight gesture of the finger, while he made a faint effort to smile, in return for the other’s salutation, the old man sat, propped up by pillows, and enveloped in shawls, pale, sad, and careworn.

“I was hesitating for two entire days, my Lord,” said Linton, lowering his voice to suit the character of the occasion, “whether I might propose to come and sit an hour with you, and I have only to beg that you will not permit me to trespass a moment longer than you feel disposed to endure me.”

“Very kind of you—most considerate, sir,” said the old peer, bowing with an air of haughty courtesy.

“You seem to gain strength every day, my Lord,” resumed Linton, who well knew there was nothing like a personal topic to awaken a sick man’s interest.

“There is something here,” said the old man, slowly, as he placed the tip of his finger on the centre of his forehead.

“Mere debility, nervous debility, my Lord. You are paying the heavy debt an overworked intellect must always acquit; but rest and repose will soon restore you.”

“Yes, sir,” muttered the other, with a weak smile, as though, without fathoming the sentiment, he felt that something agreeable to his feelings had been spoken.

“I have been impatient for your recovery, my Lord, I will confess to you, on personal grounds; I feel now how much I have been indebted to your Lordship’s counsel and advice all through life, by the very incertitude that tracks me. In fact, I can resolve on nothing, determine nothing, without your sanction.”

The old man nodded assentingly; the assurance had his most sincere conviction.

“It would seem, my Lord, that I must—whether I will or no—stand for this borough, here; there is no alternative, for you are aware that Cashel is quite unfit for public business. Each day he exhibits more and more of those qualities which bespeak far more goodness of heart than intellectual training or culture. His waywardness and eccentricity might seriously damage his own party,—could he even be taught that he had one,—and become terrible weapons in the hands of the enemy. I was speaking of Cashel, my Lord,” said Linton, as it were answering the look of inquiry in the old man’s face.

“I hate him, sir,” said the old peer, with a bitterness of voice and look that well suited the words.

“I really cannot wonder at it,” said Linton, with a deep sigh; “such duplicity is too shocking—far too shocking—to contemplate.”

“Eh! what? What did you say, sir?” cried the old man, impatiently.

“I was remarking, my Lord, that I have no confidence in his sincerity; that he strikes me as capable of playing a double part.”

A look of disappointment succeeded to the excited expression of the old man’s face; he had evidently expected some revelation, and now his features became clouded and gloomy.

“We may be unjust, my Lord,” said Linton; “it may be a prejudice on our part: others would seem to have a different estimate of that gentleman. Meek thinks highly of him.”

“Who, sir? I didn’t hear you,” asked he, snappishly.

“Meek,—Downie Meek, my Lord.”

“Pshaw!” said the old man, with a shrewd twinkle of the eye that made Linton fear the mind behind it was clearer than he suspected.

“I know, my Lord,” said he, hastily, “that you always held the worthy secretary cheap; but you weighed him in a balance too nice for the majority of people—”

“What does that old woman say? Tell me her opinion of Cashel,” said Lord Kilgoff, rallying into something like his accustomed manner. “You know whom I mean!” cried he, impatient at Linton’s delay in answering. “The old woman one sees everywhere,—she married that Scotch sergeant—”

“Lady Janet MacFarline—”

“Exactly, sir.”

“She thinks precisely with your Lordship.”

“I’m sure of it; I told my Lady so,” muttered he to himself.

Linton caught the words with eagerness, and his dark eyes kindled; for at last were they nearing the territory he wanted to occupy.

“Lady Kilgoff,” said he, slowly, “does not need any aid to appreciate him; she reads him thoroughly, the heartless, selfish, unprincipled spendthrift that he is.”

“She does not, sir,” rejoined the old man, with a loud voice, and a stroke of his cane upon the floor that echoed through the room; “you never were more mistaken in your life. His insufferable puppyism, his reckless effrontery, his underbred familiarity, are precisely the very qualities she is pleased with,—‘They are so different,’ as she says, ‘from the tiresome routine of fashionable manners.’”

“Unquestionably they are, my Lord,” said Linton, with a smile.

“Exactly, sir; they differ as do her Ladyship’s own habits from those of every lady in the peerage. I told her so; I begged to set her right on that subject, at least.”

“Your Lordship’s refinement is a most severe standard,” said Linton, bowing low.

“It should be an example, sir, as well as a chastisement. Indeed, I believe few would have failed to profit by it.” The air of insolent pride in which he spoke seemed for an instant to have brought back the wonted look to his features, and he sat up, with his lips compressed, and his chin pro-traded, as in his days of yore.

“I would entreat your Lordship to remember,” said Linton, “how few have studied in the same school you have; how few have enjoyed the intimacy of ‘the most perfect gentleman of all Europe;’ and of that small circle, who is there could have derived the same advantage from the privilege?”

“Your remark is very Just, sir. I owe much—very much—to his Royal Highness.”

The tone of humility in which he said this was a high treat to the sardonic spirit of his listener.

“And what a penance to you must be a visit in such a house as this!” said Linton, with a sigh.

“True, sir; but who induced me to make it? Answer me that.”

Linton started with amazement, for he was very far from supposing that his Lordship’s memory was clear enough to retain the events of an interview that occurred some months before.

“I never anticipated that it would cost you so dearly, my Lord,” said he, cautiously, and prepared to give his words any turn events might warrant. For once, however, the ingenuity was wasted; Lord Kilgoff, wearied and exhausted by the increased effort of his intellect, had fallen back in his chair, and, with drooping lips and fallen jaw, sat the very picture of helpless fatuity.

“So, then,” said Linton, as on tiptoe he stole noiselessly away, “if your memory was inopportune, it was, at least, very short-lived. And now, adieu, my Lord, till we want you for another act of the drama.”

We ‘ll have you at our merry-making, too. Honeymoon.

If we should appear, of late, to have forgotten some of those friends with whom we first made our readers acquainted in this veracious history, we beg to plead against any charge of caprice or neglect. The cause is simply this: a story, like a stream, has one main current; and he who would follow the broad river must eschew being led away by every rivulet which may separate from the great flood to follow its own vagrant fancy elsewhere. Now, the Kennyfecks had been meandering after this fashion for some time back. The elder had commenced a very vigorous flirtation with the dashing Captain Jennings, while the younger sister was coyly dallying under the attentions of his brother hussar,—less, be it remembered, with any direct intention of surrender, than with the faint hope that Cashel, perceiving the siege, should think fit to rescue the fortress; “Aunt Fanny” hovering near, as “an army of observation,” and ready, like the Prussians in the last war, to take part with the victorious side, whichever that might be.

And now, we ask in shame and sorrow, is it not humiliating to think, that of a party of some thirty or more, met together to enjoy in careless freedom the hospitality of a country house, all should have been animated with the same spirit of intrigue,—each bent on his own deep game, and, in some one guise or other of deceitfulness, each following out some scheme of selfish advantage?

Some may say these things are forced and unnatural; that pleasure proclaims a truce in the great war of life, where combatants lay down their weapons, and mix like friends and allies. We fear this is not the case; our own brief experiences would certainly tend to a different conclusion. Less a player than a looker-on in the great game, we have seen, through all the excitements of dissipation, all the fascinating pleasures of the most brilliant circles, the steady onward pursuit of self-interest; and, instead of the occasions of social enjoyment being like the palm-shaded wells in the desert, where men meet to taste the peacefulness of perfect rest, they are rather the arena where, in all the glitter of the most splendid armor, the combatants have come to tilt, with more than life upon the issue.

For this, the beauty wreathes herself in all the winning smiles of loveliness; for this, the courtier puts forth his most captivating address and his most seductive manner; for this, the wit sharpens the keen edge of his fancy, and the statesman matures the deep resolve of his judgment. The diamond coronets that deck the hair and add lustre to the eyes; the war-won medals that glitter on the coat of some hardy veteran; the proud insignia of merit that a sovereign’s favor grants,—all are worn to this end! Each brings to the game whatever he may possess of superiority, for the contest is ever a severe one.

And now to go back to our company. From Lady Janet, intent upon everything which might minister to her own comfort or mortify her neighbor, to the smooth and soft-voiced Downie Meek,—with the kindest of wishes and the coldest of hearts,—they were, we grieve to own it, far more imposing to look at, full dressed at dinner, than to investigate by the searching anatomy that discloses the vices and foibles of humanity; and it is, therefore, with less regret we turn from the great house, in all the pomp of its splendor, to the humble cottage where Mr. Corrigan dwelt with his granddaughter.

In wide contrast to the magnificence and profusion of the costly household, where each seemed bent on giving way to every caprice that extravagance could suggest, was the simple quietude of that unpretending family. The efforts by which Corrigan had overcome his difficulties not only cost him all the little capital he possessed in the world, but had also necessitated a mode of living more restricted than he had ever known before. The little luxuries that his station, as well as his age and long use, had made necessaries, the refinements that adorn even the very simplest lives, had all to be, one by one, surrendered. Some of these he gave up manfully, others cost him deeply; and when the day came that he had to take leave of his old gray pony, the faithful companion of so many a lonely ramble, the creature he had reared and petted like a dog, the struggle was almost too much for him.

He walked along beside the man who led the beast to the gate, telling him to be sure and seek out some one who would treat her kindly. “Some there are would do so for my sake; but she deserves it better for her own.—Yes, Nora, I ‘m speaking of you,” said he, caressing her, as she laid her nose over his arm. “I’m sure I never thought we’d have to part.”

“She’s good as goold this minit,” said the man; “an’ it’ll go hard but ‘ll get six pounds for her, any way.”

“Tell whoever buys her that Mr. Corrigan will give him a crown-piece every Christmas-day that he sees her looking well and in good heart. To be sure, it’s no great bribe, we’re both so old,” said he, smiling; “but my blessing goes with the man that’s a friend to her.” He sat down as he said this, and held his hand over his face till she was gone. “God forgive me, if I set my heart too much on such things, but it’s like parting with an old friend. Poor Mary’s harp must go next. But here comes Tiernay. Well, doctor, what news?”

The doctor shook his head twice or thrice despondingly, but said nothing; at last, he muttered, in a grumbling voice,—

“I was twice at the Hall, but there’s no seeing Cashel himself; an insolent puppy of a valet turned away contemptuously as I asked for him, and said,—

“Mr. Linton, perhaps, might hear what you have to say.’”

“Is Kennyfeck to be found?”

“Yes, I saw him for a few minutes; but he’s like the rest of them. The old fool fancies he ‘s a man of fashion here, and told me he had left ‘the attorney’ behind, in Merrion Square. He half confessed to me, however, what I feared. Cashel has either given a promise to give this farm of yours to Linton—”

“Well, the new landlord will not be less kind than the old one.”

“You think so,” said Tiernay, sternly. “Is your knowledge of life no better than this? Have you lived till now without being able to read that man? Come, come, Corrigan, don’t treat this as a prejudice of mine; I have watched him closely, and he sees it. I tell you again, the fellow is a villain.”

“Ay, ay,” said Corrigan, laughing; “your doctor’s craft has made you always on the look-out for some hidden mischief.”

“My doctor’s craft has taught me to know that symptoms are never without a meaning. But enough of him. The question is simply this: we have, then, merely to propose to Cashel the purchase of your interest in the cottage, on which you will cede the possession.”

“Yes; and give up, besides, all claim at law; for you know we are supported by the highest opinions.”

“Pooh! nonsense, man; don’t embarrass the case by a pretension they ‘re sure to sneer at. The cottage and the little fields behind it are tangible and palpable; don’t weaken your case by a plea you could not press.”

“Have your own way, then,” said the old man, mildly.

“It is an annuity, you say, you ‘d wish?”

“On Mary’s life, not on mine, doctor.”

“It will be a poor thing,” said Tiernay, with a sigh.

“They say we could live in some of the towns in Flanders very cheaply,” said Corrigan, cheerfully.

“You don’t know how to live cheaply,” rejoined Tiernay, crankily. “You think, if you don’t see a man in black behind your chair, and that you eat off delf instead of silver, that you are a miracle of simplicity. I saw you last Sunday put by the decanter with half a glass of sherry at the bottom of it, and you were as proud of your thrift as if you had reformed your whole household.”

“Everything is not learned in a moment, Tiernay,” said Corrigan, mildly.

“You are too old to begin, Con Corrigan,” said the other, gravely. “Such men as you, who have not been educated to narrow fortunes, never learn thrift; they can endure great privations well enough, but it is the little, petty, dropping ones that break down the spirit,—these they cannot meet.”

“A good conscience and a strong will can do a great deal, Tiernay. One thing is certain,—that we shall escape persecution from him. He will scarcely discover us in our humble retreat.”

“I’ve thought of that too,” said Tiernay; “it is the greatest advantage the plan possesses. Now, the next point is, how to see this same Cashel; from all that I can learn, his life is one of dissipation from morning till night. Those fashionable sharpers by whom he is surrounded are making him pay dearly for his admission into the honorable guild.”

“The greater the pity,” sighed Corrigan; “he appeared to me deserving of a different fate. An easy, complying temper—”

“The devil a worse fault I ‘d with my enemy,” broke in Tiernay, passionately. “A field without a fence,—a house without a door to it! And there, if I am not mistaken, I hear his voice; yes, he ‘s coming along the path, and some one with him too.”

“I ‘ll leave you to talk to him, Tiernay, for you seem in ‘the vein.’” And with these words the old man turned into a by-path, just as Cashel, with Lady Kilgoff on his arm, advanced up the avenue.

Nothing is more remarkable than the unconscious homage tendered to female beauty and elegance by men whose mould of mind, as well as habit, would seem to render them insensible to such fascinations, nor is their instinctive admiration a tribute which beauty ever despises.

The change which came over the rough doctor’s expression as the party came nearer exemplified this truth strongly. The look of stern determination with which he was preparing to meet Cashel changed to one of astonishment, and, at last, to undisguised admiration, as he surveyed the graceful mien and brilliant beauty before him. They had left the phaeton at the little wicket, and the exercise on foot had slightly colored her cheek, and added animation to her features,—the only aid necessary to make her loveliness perfect.

“I have taken a great liberty with my neighbor, Doctor Tiernay,” said Cashel, as he came near. “Let me present you, however, first,—Doctor Tiernay, Lady Kilgoff. I had been telling her Ladyship that the only picturesque portion of this country lies within this holly enclosure, and is the property of my friend Mr. Corrigan, who, although he will not visit me, will not, I ‘m sure, deny me the pleasure of showing his tasteful grounds to my friends.”

“My old friend would be but too proud of such a visitor,” said Tiernay, bowing low to Lady Kilgoff.

“Mr. Cashel has not confessed all our object, Mr. Tiernay,” said she, assuming her most gracious manner. “Our visit has in prospect the hope of making Miss Leicester’s acquaintance; as I know you are the intimate friend of the family, will you kindly say if this be a suitable hour, or, indeed, if our presence here at all would not be deemed an intrusion?”

The doctor colored deeply, and his eye sparkled with pleasure; for strange enough as it may appear, while sneering at the dissipations of the great house, he felt a degree of indignant anger at the thought of Mary sitting alone and neglected, with gayeties around her on every side.

“It was a most thoughtful kindness of your Ladyship,” replied he, “for my friend is too old and too infirm to seek society; and so the poor child has no other companionship than two old men, only fit to weary each other.”

“You make me hope that our mission will succeed, sir,” said Lady Kilgoff, still employing her most fascinating look and voice; “we may reckon you as an ally, I trust.”

“I am your Ladyship’s most devoted,” said the old man, courteously; “how can I be of service?”

“Our object is to induce Miss Leicester to pass some days with us,” said she. “We are plotting various amusements that might interest her,—private theatricals among the rest.”

“Here she comes, my Lady,” said Tiernay, with animation; “I am proud to be the means of introducing her.”

Just at this instant Mary Leicester had caught sight of the party, and, uncertain whether to advance or retire, was standing for a moment undecided, when Tiernay called out:

“Stay a minute, Miss Mary; Lady Kilgoff is anxious to make your acquaintance.”

“This is a very informal mode of opening an intimacy, Miss Leicester,” said Lady Kilgoff; “pray let it have the merit of sincerity, for I have long desired to know one of whom I have heard so much.”

Mary replied courteously to the speech, and looked pleasedly towards Cashel, to whom she justly attributed the compliment insinuated.

As the two ladies moved on side by side, engaged in conversation, Tiernay slackened his pace slightly, and, in a voice of low but earnest import, said,—

“Will Mr. Cashel consider it an intrusion if I take this opportunity of speaking to him on a matter of business?”

“Not in the least, doctor,” said Cashel, gayly; “but it’s right I should mention that I am most lamentably ignorant of everything that deserves that name. My agent has always saved me from the confession, but the truth will out at last.”

“So much the worse, sir,—for others as well as for yourself,” replied Tiernay, bluntly. “The trust a large fortune imposes—But I shall forget myself if I touch on such a theme. My business is this, sir,—and, in mercy to you, I ‘ll make it very brief. My old friend, Mr. Corrigan, deems it expedient to leave this country, and, in consequence, to dispose of the interest he possesses in these grounds, so long embellished by his taste and culture. He is well aware that much of what he has expended here has not added substantial value to the property; that, purely ornamental, it has, in great part, repaid himself by the many years of enjoyment it has afforded him. Still, he hopes, or, rather, I do for him,—for, to speak candidly, sir, he has neither courage nor hardihood for these kind of transactions,—I hope, sir, that you, desirous of uniting this farm to the large demesne, as I understand to be the case, will not deem this an unfitting occasion to treat liberally with one whose position is no longer what it once was. I must take care, Mr. Cashel, that I say nothing which looks like solicitation here; the confidence my friend has placed in me would be ill requited by such an error.”

“Is there no means of securing Mr. Corrigan’s residence here?” said Cashel. “Can I not accommodate his wishes in some other way, and which should not deprive me of a neighbor I prize so highly?”

“I fear not. The circumstances which induce him to go abroad are imperative.”

“Would it not be better to reflect on this?” said Cashel. “I do not seek to pry into concerns which are not mine, but I would earnestly ask if some other arrangement be not possible?”

Tiernay shook his head dubiously.

“If this be so, then I can oppose no longer. It only remains for Mr. Corrigan to put his own value on the property, and I accept it.”

“Nay, sir; this generosity will but raise new difficulties. You are about to deal with a man as high-hearted as yourself, and with the punctilious delicacy that a narrow fortune suggests, besides.”

“Do you, then, doctor, who know both of us, be arbitrator. Let it not be a thing for parchments and lawyers’ clerks; let it be an honorable understanding between two gentlemen, and so, no more of it.”

“If the world were made up of men like yourself and my old friend, this would be, doubtless, the readiest and the best solution of the difficulty,” said Tiernay; “but what would be said if we consented to such an arrangement? What would not be said? Ay, faith, there’s not a scandalous rumor that malice could forge would not be rife upon us.”

“And do you think such calumnies have any terror for me?” cried Cashel.

“When you’ve lived to my age, sir, you’ll reason differently.”

“It shall be all as you wish, then,” said Cashel. “But stay!” cried he, after a moment’s thought; “there is a difficulty I had almost forgotten. I must look that it may not interfere with our plans. When can I see you again? Would it suit you to come and breakfast with me tomorrow? I ‘ll have my man of business, and we ‘ll arrange everything.”

“Agreed, sir; I’ll not fail. I like your promptitude. A favor is a double benefit when speedily granted.”

“Now I shall ask one from you, doctor. If I can persuade my kind friends here to visit us, will you too be of the party sometimes?”

“Not a bit of it. Why should I, sir, expose you to the insolent criticism my unpolished manners and rude address would bring upon you—or myself to the disdain that fashionable folk would show me? I am proud—too proud, perhaps—at the confidence you would repose in my honor; I don’t wish to blush for my breeding by way of recompense. There, sir,—there is one yonder in every way worthy all the distinction rank and wealth can give her. I feel happy to think that she is to move amongst those who, if they cannot prize her worth, will at least appreciate her fascinations.”

“Will Mr. Corrigan consent?”

“He must,—he shall,” broke in Tiernay; “I’ll insist upon it But come along with me into the cottage, while the ladies are cementing their acquaintance; we’ll see him, and talk him over.”

So saying, he led Cashel into the little library, where, deep sunk in his thoughts, the old man was seated, with an open book before him, but of which he had not read a line.

“Con!” cried Tiernay, “Mr. Cashel has come to bring you and Miss Mary up to the Hall to dinner. There, sir, look at the face he puts on,—an excuse in every wrinkle of it!”

“But, my dear friend—my worthy doctor—you know perfectly—-”

“I ‘ll know perfectly that you must go,—no help for it I have told Mr. Cashel that you ‘d make fifty apologies—pretend age—Ill-health—want of habit, and so on; the valid reason being that you think his company a set of raffs, and—”

“Oh, Tiernay, I beg you ‘ll not ascribe such sentiments to me.”

“Well, I thought so myself, t’ other day,—ay, half-an-hour ago; but there is a lady yonder, walking up and down the grass-plot, has made me change my mind. Come out and see her, man, and then say as many ‘No’s’ as you please.” And, half-dragging, half-leading the old man out, Tiernay went on:—

“You ‘ll see, Mr. Cashel, how polite he ‘ll grow when he sees the bright eyes and the fair cheek. You ‘ll not hear of any more refusals then, I promise you.”

Meanwhile, so far had Lady Kilgoff advanced in the favorable opinion of Miss Leicester that the young girl was already eager to accept the proffered invitation. Old Mr. Corrigan, however, could not be induced to leave his home, and so it was arranged that Lady Kilgoff should drive over on the following day to fetch her; with which understanding they parted, each looking forward with pleasure to their next meeting.

“Gone! and in secret, too!”

Amid all the plans for pleasure which engaged the attention of the great house, two subjects now divided the interest between them. One was the expected arrival of the beautiful Miss Leicester,—“Mr. Cashel’s babe in the wood,” as-Lady Janet called her,—the other, the reading of a little one-act piece which Mr. Linton had written for the company. Although both were, in their several ways, “events,” the degree of interest they excited was very disproportioned to their intrinsic consequence, and can only be explained by dwelling on the various intrigues and schemes by which that little world was agitated.

Lady Janet, whose natural spitefulness was a most catholic feeling, began to fear that Lady Kilgoff had acquired such an influence over Cashel that she could mould him to any course she pleased,—even a marriage. She suspected, therefore, that this rustic beauty had been selected by her Ladyship as one very unlikely to compete with herself in Roland’s regard, and that she was thus securing a lasting ascendancy over him.

Mrs. Leicester White, who saw, or believed she saw, herself neglected by Roland, took an indignant view of the matter, and threw out dubious and shadowy suspicions about “who this young lady might be, who seemed so opportunely to have sprung up in the neighborhood,” and expressed, in confidence, her great surprise “how Lady Kilgoff could lend herself to such an arrangement.”

Mrs. Kennyfeck was outraged at the entrance of a new competitor into the field, where her daughter was no longer a “favorite.” In fact, the new visitor’s arrival was heralded by no signs of welcome, save from the young men of the party, who naturally were pleased to hear that a very handsome and attractive girl was expected.

As for Aunt Fanny, her indignation knew no bounds; indeed, ever since she had set foot in the house her state had been one little short of insanity. In her own very graphic phrase, “She was fit to be tied at all she saw.” Now, when an elderly maiden lady thus comprehensively sums up the cause of her anger, without descending to “a bill of particulars,” the chances are that some personal wrong—real or imaginary—is more in fault than anything reprehensible in the case she is so severe upon. So was it here. Aunt Fanny literally saw nothing, although she heard a great deal. Daily, hourly, were the accusations of the whole Kennyfeck family directed against her for the loss of Cashel. But for her, and her absurd credulity on the statement of an anonymous letter, and there had been no yacht voyage with Lady Kilgoff—no shipwreck—no life in a cabin on the coast—no——In a word, all these events had either not happened at all, or only occurred with Livy Kennyfeck for their heroine.

Roland’s cold, almost distant politeness to the young ladies, was marked enough to appear intentional; nor could all the little by-play of flirtation with others excite in him the slightest evidence of displeasure. If the family were outraged at this change, poor Livy herself bore up admirably; and while playing a hundred little attractive devices for Cashel, succeeded in making a very deep impression on the well-whiskered Sir Harvey Upton, of the—th. Indeed, as Linton, who saw everything, shrewdly remarked, “She may not pocket the ball she intended, but, rely on’t, she ‘ll make a ‘hazard’ somewhere.”