The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Day's Ride, by Charles James Lever

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: A Day's Ride

A Life's Romance

Author: Charles James Lever

Illustrator: W. Cubitt Cooke

Release Date: June 4, 2010 [EBook #32692]

Last Updated: September 4, 2016

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A DAY'S RIDE ***

Produced by David Widger

CONTENTS

A DAY’S RIDE

CHAPTER I. I PREPARE TO SEEK ADVENTURES

CHAPTER II. BLONDEL AND I SET OUT

CHAPTER III. TRUTH NOT ALWAYS IN WINE

CHAPTER IV. PLEASANT REFLECTIONS ON AWAKING

CHAPTER V. THE ROSARY AT INISTIOGE

CHAPTER VI. MY SELF-EXAMINATION

CHAPTER VII. FATHER DYKE’S LETTER

CHAPTER VIII. IMAGINATION STIMULATED BY BRANDY AND WATER

CHAPTER IX. HIS INTEREST IN A LADY FELLOW-TRAVELLER

CHAPTER X. THE PERILS OF MY JOURNEY TO OSTEND

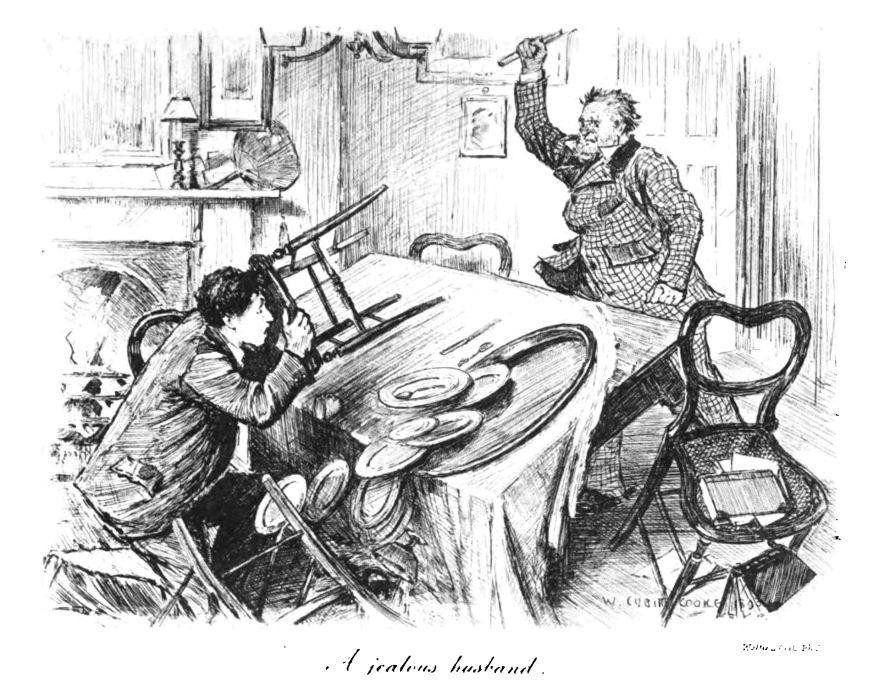

CHAPTER XI. A JEALOUS HUSBAND

CHAPTER XII. THE DUCHY OF HESSE-KALBBRATONSTADT

CHAPTER XIII. I CALL AT THE BRITISH LEGATION

CHAPTER XIV. SHAMEFUL NEGLECT OF A PUBLIC SERVANT

CHAPTER XV. I LECTURE THE AMBASSADOR’S SISTER

CHAPTER XVI. UNPLEASANT TURN TO AN AGREEABLE CONVERSE

CHAPTER XVII. MRS. KEATS MOVES MY INDIGNATION

CHAPTER XVIII. AN IMPATIENT SUMMONS

CHAPTER XIX. MRS. KEATS’S MYSTERIOUS COMMUNICATION

CHAPTER XX. THE MYSTERY EXPLAINED

CHAPTER XXI. HOW I PLAY THE PRINCE

CHAPTER XXII. INCIDENTS OF THE SECOND DAY’S JOURNEY

CHAPTER XXIII. JEALOUSY UNSUPPORTED BY COURAGE

CHAPTER XXIV. MY CANDOR AS AN AUTOBIOGRAPHER

CHAPTER XXV. I MAINTAIN A DIGNIFIED RESERVE

CHAPTER XXVI. VATERCHEN AND TINTEFLECK

CHAPTER XXVII. I ATTEMPT TO OVERTHROW SOCIAL PREJUDICES

CHAPTER XXVIII. RESULTS OF THE EXPERIMENT

CHAPTER XXIX. ON FOOT AND IN LOW COMPANY

CHAPTER XXX. VATERCHEN’S NARRATIVE

CHAPTER XXXI. A GENIUS FOR CARICATURE

CHAPTER XXXII. I RELIEVE MYSELF OF MY PURSE

CHAPTER XXXIII. MY ELOQUENCE BEFORE THE CONSTANCE MAGISTRATES

CHAPTER XXXIV. A SUMPTUOUS DINNER AND AN EMPTY POCKET

CHAPTER XXXV. HART CROFTON’S COMMISSION

CHAPTER XXXVI. FURTHER INTERCOURSE WITH HARPAR

CHAPTER XXXVII. MY EXPLOSION AT THE TABLE D’HÔTE

CHAPTER XXXVIII. THE DUEL WITH PRINCE MAX

CHAPTER XXXIX. ON THE EDGE OF A TORRENT

CHAPTER XL. I AM DRAGGED AS A PRISONER TO FELDKIRCH

CHAPTER XLI. THE ACT OF ACCUSATION

CHAPTER XLII. A GLIMPSE OF AN OLD FRIEND

CHAPTER XLIII. I AM CONFINED IN THE AMBRAS SCHLOSS

CHAPTER XLIV. A VISIT FROM THE HON. GREY BULLER

CHAPTER XLV. MY CANDID AVOWAL TO KATE HERBERT

CHAPTER XLVI. CAPTAIN ROGERS STANDS MY FRIEND

CHAPTER XLVII. MY DUELLING AMBITION AGAIN DISAPPOINTED

CHAPTER XLVIII. FINAL ADVENTURES AND SETTLEMENT

It has been said that any man, no matter how small and insignificant the post he may have filled in life, who will faithfully record the events in which he has borne a share, even though incapable of himself deriving profit from the lessons he has learned, may still be of use to others,—sometimes a guide, sometimes a warning. I hope this is true. I like to think it so, for I like to think that even I,—A. S. P.,—if I cannot adorn a tale, may at least point a moral.

Certain families are remarkable for the way in which peculiar gifts have been transmitted for ages. Some have been great in arms, some in letters, some in statecraft, displaying in successive generations the same high qualities which had won their first renown. In an humble fashion, I may lay claim to belong to this category. My ancestors have been apothecaries for one hundred and forty-odd years. Joseph Potts, “drug and condiment man,” lived in the reign of Queen Anne, at Lower Liffey Street, No. 87; and to be remembered passingly, has the name of Mr. Addison amongst his clients,—the illustrious writer having, as it would appear, a peculiar fondness for “Pott’s linature,” whatever that may have been; for the secret died out with my distinguished forefather. There was Michael Joseph Potts, “licensed for chemicals,” in Mary’s Abbey, about thirty years later; and so we come on to Paul Potts and Son, and then to Launcelot Peter Potts, “Pharmaceutical Chemist to his Excellency and the Irish Court,” the father of him who now bespeaks your indulgence.

My father’s great misfortune in life was the ambition to rise above the class his family had adorned for ages. He had, as he averred, a soul above senna, and a destiny higher than black drop. He had heard of a tailor’s apprentice becoming a great general. He had himself seen a wig-maker elevated to the woolsack; and he kept continually repeating, “Mine is the only walk in life that leads to no high rewards. What matters it whether my mixtures be addressed to the refined organization of rank, or the dura ilia rasorum?—I shall live and die an apothecary. From every class are men selected for honors save mine; and though it should rain baronetcies, the bloody hand would never fall to the lot of a compounding chemist.”

“What do you intend to make of Algernon Sydney, Mr. Potts?” would say one of his neighbors. “Bring him up to your own business? A first-rate connection to start with in life.”

“My own business, sir? I’d rather see him a chimneysweep.”

“But, after all, Mr. Potts, being so to say, at the head of your profession—”

“It is not a profession, sir. It is not even a trade. High science and skill have long since left our insulted and outraged ranks; we are mere commission agents for the sale of patent quackeries. What respect has the world any longer for the great phials of ruby, and emerald, and marine blue, which, at nightfall, were once the magical emblems of our mysteries, seen afar through the dim mists of lowering atmospheres, or throwing their lurid glare upon the passers-by? What man, now, would have the courage to adorn his surgery—I suppose you would prefer I should call it a 'shop’—with skeleton-fishes, snakes, or a stuffed alligator? Who, in this age of chemical infidelity, would surmount his door with the ancient symbols of our art,—the golden pestle and mortar? Why, sir, I’d as soon go forth to apply leeches on a herald’s tabard, or a suit of Milan mail. And what have they done, sir?” he would ask, with a roused indignation,—“what have they done by their reforms? In invading the mystery of medicine, they have ruined its prestige. The precious drops you once regarded as the essence of an elixir vitæ, and whose efficacy lay in your faith, are now so much strychnine, or creosote, which you take with fear and think over with foreboding.”

I suppose it can only be ascribed to that perversity which seems a great element in human nature, that, exactly in the direct ratio of my father’s dislike to his profession was my fondness for it. I used to take every opportunity of stealing into the laboratory, watching intently all the curious proceedings that went on there, learning the names and properties of the various ingredients, the gases, the minerals, the salts, the essences; and although, as may be imagined, science took, in these narrow regions, none of her loftiest flights, they were to me the most marvellous and high-soaring efforts of human intelligence. I was just at that period of life—the first opening of adolescence—when fiction and adventure have the strongest bold upon our nature, my mind filled with the marvels of Eastern romance, and imbued with a sentiment, strong as any conviction, that I was destined to a remarkable life. I passed days in dreamland,—what I should do in this or that emergency; how rescue myself from such a peril; how profit by such a stroke of fortune; by what arts resist the machinations of this adversary; how conciliate the kind favor of that. In the wonderful tales that I read, frequent mention was made of alchemy and its marvels; now the search was for some secret of endless wealth; now, it was for undying youth or undecay-ing beauty; while in other stories I read of men who had learned how to read the thoughts, trace the motives, and ultimately sway the hearts of their fellow-men, till life became to them a mere field for the exercise of their every will and caprice, throwing happiness and misery about them as the humor inclined. The strange life of the laboratory fitted itself exactly to this phase of my mind.

The wonders it displayed, the endless combinations and transformations it effected, were as marvellous as any that imaginative fiction could devise; but even these were nothing compared to the mysterious influence of the place itself upon my nervous system, particularly when I found myself there alone. In the tales with which my head was filled, many of them the wild fancies of Grimm, Hoffman, or Musæus, nothing was more common than to read how some eager student of the black art, deep in the mystery of forbidden knowledge, had, by some chance combination, by some mere accidental admixture of this ingredient with that, suddenly arrived at the great secret, that terrible mystery which for centuries and centuries had evaded human search. How often have I watched the fluid as it boiled and bubbled in the retort, till I thought the air globules, as they came to the surface, observed a certain rhythm and order. Were these, words? Were they symbols of some hidden virtue in the liquid? Were there intelligences to whom these could speak, and thus reveal a wondrous history? And then, again, with what an intense eagerness have I gazed on the lurid smoke that arose from some smelting mass, now fancying that the vapor was about to assume form and substance, and bow imagining that it lingered lazily, as though waiting for some cabalistic word of mine to give it life and being? How heartily did I censure the folly that had ranked alchemy amongst the absurdities of human invention! Why, rather, had not its facts been treasured and its discoveries recorded, so that in some future age a great intelligence arising might classify and arrange them, showing at least what were practicable and what were only evasive. Alchemists were, certainly, men of pure lives, self-denying and humble. They made their art no stepping-stone to worldly advancement or success; they sought no favor from princes, nor any popularity from the people; but, retired and estranged from all the pleasures of the world, followed their one pursuit, unnoticed and unfriended. How cruel, therefore, to drag them forth from their lonely cells, and expose them to the gaping crowd as devil worshippers! How inhuman to denounce men whose only crimes were lives of solitude and study! The last words of Peter von Vordt, burned for a wizard, at Haarlem, in 1306, were, “Had they left this poor head a little longer on my shoulders, it would have done more for human happiness than all this bonfire!”

How rash and presumptuous is it, besides, to set down any fixed limits to man’s knowledge! Is not every age an advance upon its predecessors, and are not the commonest acts of our present civilization perfect miracles as compared with the usages of our ancestors? But why do I linger on this theme, which I only introduced to illustrate the temper of my boyish days? As I grew older, books of chivalry and romance took possession of my mind, and my passion grew for lives of adventure. Of all kinds of existence, none seemed to me so enviable as that of those men who, regarding life as a vast ocean, hoisted sail, and set forth, not knowing nor caring whither, but trusting to their own manly spirit for extrication out of whatever difficulties might beset them. What a narrow thing, after all, was our modern civilization, with all its forms and conventionalities, with its gradations of rank and its orders! How hopeless for the adventurous spirit to war with the stern discipline of an age that marshalled men in ranks like soldiers, and told that each could only rise by successive steps! How often have I wondered was there any more of adventure left in life? Were there incidents in store for him who, in the true spirit of an adventurer, should go in search of them? As for the newer worlds of Australia and America, they did not possess for me much charm. No great association linked them with the past; no echo came out of them of that heroic time of feudalism, so peopled with heart-stirring characters. The life of the bush or the prairie had its incidents, but they were vulgar and commonplace; and worse, the associates and companions of them were more vulgar still. Hunting down Pawnees or buffaloes was as mean and ignoble a travesty of feudal adventure as was the gold diggings at Bendigo of the learned labors of the alchemist. The perils were unexciting, the rewards prosaic and commonplace. No. I felt that Europe—in some remote regions—and the East—in certain less visited tracts—must be the scenes best suited to my hopes. With considerable labor I could spell my way through a German romance, and I saw, in the stories of Fouqué, and even of Goethe, that there still survived in the mind of Germany many of the features which gave the color-ing to a feudal period. There was, at least, a dreamy indifference to the present, a careless abandonment to what the hour might bring forth, so long as the dreamer was left to follow out his fancies in all their mysticism, that lifted men out of the vulgarities of this work-o’-day world; and I longed to see a society where learning consented to live upon the humblest pittance, and beauty dwelt unflattered in obscurity.

I was now entering upon manhood; and my father—having, with that ambition so natural to an Irish parent who aspires highly for his only son, destined me for the bar—made me a student of Trinity College, Dublin.

What a shock to all the romance of my life were the scenes into which I now was thrown! With hundreds of companions to choose from, I found not one congenial to me. The reading men, too deeply bent upon winning honors, would not waste a thought upon what could not advance their chances of success. The idle, only eager to get through their career undetected in their ignorance, passed lives of wild excess or stupid extravagance.

What was I to do amongst such associates? What I did do,—avoid them, shun them, live in utter estrangement from all their haunts, their ways, and themselves. If the proud man who has achieved success in life encounters immense difficulties when, separating himself from his fellows, he acknowledges no companionship, nor admits any to his confidence, it may be imagined what must be the situation of one who adopts this isolation without any claim to superiority whatever. As can easily be supposed, I was the butt of my fellow students, the subject of many sarcasms and practical jokes. The whole of my Freshman year was a martyrdom. I had no peace, was rhymed on by poetasters, caricatured by draughtsmen, till the name of Potts became proverbial for all that was eccentric, ridiculous, and absurd.

Curran has said, “One can’t draw an indictment against a nation;” in the same spirit did I discover “one cannot fight his whole division.” For a while I believe I experienced a sort of heroism in my solitary state; I felt the spirit of a Coriolanus in my heart, and muttered, “I banish you! ” but this self-supplied esteem did not last long, and I fell into a settled melancholy. The horrible truth was gradually forcing its way slowly, clearly, through the mists of my mind, that there might be something in all this sarcasm, and I can remember to this hour, the day—ay, and the very place—wherein the questions flashed across me: Is my hair as limp, my nose as long, my back as arched, my eyes as green as they have pictured them? Do I drawl so fearfully in my speech? Do I drag my heavy feet along so ungracefully? Good heavens! have they possibly a grain of fact to sustain all this fiction against me?

And if so,—horrible thought,—am I the stuff to go forth and seek adventures? Oh, the ineffable bitterness of this reflection! I remember it in all its anguish, and even now, after years of such experience as have befallen few men, I can recall the pain it cost me. While I was yet in the paroxysm of that sorrow, which assured me that I was not made for doughty deeds, nor to captivate some fair princess, I chanced to fall upon a little German volume entitled “Wald Wandelungen und Abentheure,” von Heinrich Stebbe. Forest rambles and adventures, and of a student, too! for so Herr Stebbe announces himself, in a short introduction to the reader. I am not going into any account of his book. It is in Voss’s Leipzig Catalogue, and not unworthy of perusal by those who are sufficiently imbued with Germanism to accept the changeful moods of a mystical mind, with all its visionary glimpses of light and shade, its doubts, fears, hopes, and fancies, in lieu of real incidents and actual events. Of adventures, properly speaking, he had none. The people he met, the scenes in which he bore his part, were as commonplace as need be. The whole narrative never soared above that bread and butter life—Butter-brod Leben—which Germany accepts as romance; but, meanwhile, the reflex of whatever passed around him in the narrator’s own mind was amusing; so ingeniously did he contrive to interweave the imaginary with the actual, throwing over the most ordinary pictures of life a sort of hazy indistinctness,—meet atmosphere for mystical creation.

If I did not always sympathize with him in his brain-wrought wanderings, I never ceased to take pleasure in his description of scenery, and the heartfelt delight he experienced in Journeying through a world so beautiful and so varied. There was also a little woodcut frontispiece which took my fancy much, representing him as he stood leaning on his horse’s mane, gazing rapturously on the Elbe, from one of the cliffs off the Saxon Switzerland. How peaceful he looked, with his long hair waving gracefully on his neck, and his large soft eyes turned on the scene beneath him I His clasped hands, as they lay on the horse’s mane, imparted a sort of repose, too, that seemed to say, “I could linger here ever so long.” Nor was the horse itself without a significance in the picture; he was a long-maned, long-tailed, patient-looking beast, well befitting an enthusiast, who doubtless took but little heed of how he went or where. If his lazy eye denoted lethargy, his broad feet and short legs vouched for his sure-footedness.

Why should not I follow Stebbe’s example? Surely there was nothing too exalted or extravagant in his plan of life. It was simply to see the world as it was, with the aid of such combinations as a fertile fancy could contribute; not to distort events, but to arrange them, Just as the landscape painter in the license of his craft moves that massive rock more to the foreground, and throws that stone pine a little further to the left of his canvas. There was, indeed, nothing to prevent my trying the experiment Ireland was not less rich in picturesque scenery than Germany, and if she boasted no such mighty stream as the Elbe, the banks of the Blackwater and the Nore were still full of woodland beauty; and, then, there was lake scenery unrivalled throughout Europe.

I turned to Stebbe’s narrative for details of his outfit. His horse be bought at Nordheim for two hundred and forty gulden,—about ten pounds; his saddle and knapsack cost him a little more than forty shillings; with his map, guide-book, compass, and some little extras, all were comprised within twenty pounds sterling,—surely not too costly an equipage for one who was adventuring on a sea wide as the world itself.

As my trial was a mere experiment, to be essayed on the most limited scale, I resolved not to buy, but only hire a horse, taking him by the day, so that if any change of mind or purpose supervened I should not find myself in any embarrassment.

A fond uncle had just left me a legacy of a hundred pounds, which, besides, was the season of the long vacation; thus did everything combine to favor the easy execution of a plan which I determined forthwith to put into practice.

“Something quiet and easy to ride, sir, you said?” repeated Mr. Dycer after me, as I entered his great establishment for the sale and hire of horses. “Show the gentleman four hundred and twelve.”

“Oh, Heaven forbid!” I exclaimed, in ignorance; “such a number would only confuse me.”

“You mistake me, sir,” blandly interposed the dealer; “I meant the horse that stands at that number. Lead him out, Tim. He ‘s gentle as a lamb, sir, and, if you find he suits you, can be had for a song,—I mean a ten pound note.”

“Has he a long mane and tail?” I asked, eagerly.

“The longest tail and the fullest mane I ever saw. But here he comes.” And with the word, there advanced towards us, at a sort of easy amble, a small-sized cream-colored horse, with white mane and tail. Knowing nothing of horseflesh, I was fain to content myself with such observations as other studies might supply me with; and so I closely examined his head, which was largely developed in the frontal region, with moral qualities fairly displayed. He had memory large, and individuality strong; nor was wit, if it exist in the race, deficient Over the orbital region the depressions were deep enough to contain my closed fist, and when I remarked upon them to the groom, he said, “‘T is his teeth will tell you the rayson of that;” a remark which I suspect was a sarcasm upon my general ignorance.

I liked the creature’s eye. It was soft, mild, and contemplative; and although not remarkable for brilliancy, possessed a subdued lustre that promised well for temper and disposition.

“Ten shillings a day,—make it three half-crowns by the week, sir. You ‘ll never hit upon the like of him again,” said the dealer, hurriedly, as he passed me, on his other avocations.

“Better not lose him, sir; he’s well known at Batty’s, and they ‘ll have him in the circus again if they see him. Wish you saw him with his fore-legs on a table, ringing the bell for his breakfast.*’

“I’ll take him by the week, though, probably, a day or two will be all I shall need.”

“Four hundred and twelve for Mr. Potts,” Dycer screamed out. “Shoes removed, and to be ready in the morning.”

I had heard and read frequently of the exhilarating sensations of horse exercise. My fellow-students were full of stories of the hunting-field and the race-course. Wherever, indeed, a horse figured in a narrative, there was an almost certainty of meeting some incident to stir the blood and warm up enthusiasm. Even the passing glimpses one caught of sporting-prints in shop-windows were suggestive of the pleasure imparted by a noble and chivalrous pastime. I never closed my eyes all night, revolving such thoughts in my head. I had so worked up my enthusiasm that I felt like one who is about to cross the frontier of some new land where people, language, ways, and habits are all unknown to him. “By this hour to-morrow night,” thought I, “I shall be in the land of strangers, who have never seen, nor so much as heard of me. There will invade no traditions of the scoffs and jibes I have so long endured; none will have received the disparaging estimate of my abilities, which my class-fellows love to propagate; I shall simply be the traveller who arrived at sundown mounted on a cream-colored palfrey,—a stranger, sad-looking, but gentle, withal, of courteous address, blandly demanding lodging for the night. ‘Look to my horse, ostler,’ shall I say, as I enter the honeysuckle-covered porch of the inn. ‘Blondel’—I will call him Blondel—‘is accustomed to kindly usage.’” With what quiet dignity, the repose of a conscious position, do I follow the landlord as he shows me to my room. It is humble, but neat and orderly. I am contented. I tell him so. I am sated and wearied of luxury; sick of a gilded and glittering existence. I am in search of repose and solitude. I order my tea; and, if I ask the name of the village, I take care to show by my inattention that I have not heard the answer, nor do I care for it.

Now I should like to hear how they are canvassing me in the bar, and what they think of me in the stable. I am, doubtless, a peer, or a peer’s eldest son. I am a great writer, the wondrous poet of the day; or the pre-Raphaelite artist; or I am a youth heart-broken by infidelity in love; or, mayhap, a dreadful criminal. I liked this last the best, the interest was so intense; not to say that there is, to men who are not constitutionally courageous, a strong pleasure in being able to excite terror in others.

But I hear a horse’s feet on the silent street. I look out Day is just breaking. Tim is holding Blondel at the door. My hour of adventure has struck, and noiselessly descending the stairs, I issue forth.

“He is a trifle tender on the fore-feet, your honor,” said Tim, as I mounted; “but when you get him off the stones on a nice piece of soft road, he ‘ll go like a four-year-old.”

“But he is young, Tim, isn’t he?” I asked, as I tendered him my half-crown.

“Well, not to tell your honor a lie, he is not,” said Tim, with the energy of a man whose veracity had cost him little less than a spasm.

“How old would you call him, then?” I asked, in that affected ease that seemed to say, “Not that it matters to me if he were Methuselah.”

“I could n’t come to his age exactly, your honor,” he replied, “but I remember seeing him fifteen years ago, dancing a hornpipe, more by token for his own benefit; it was at Cooke’s Circus, in Abbey Street, and there wasn’t a hair’s difference between him now and then, except, perhaps, that he had a star on the forehead, where you just see the mark a little darker now.”

“But that is a star, plain enough,” said I, half vexed.

“Well, it is, and it is not,” muttered Tim, doggedly, for he was not quite satisfied with my right to disagree with him.

“He’s gentle, at all events?” I said, more confidently.

“He’s a lamb!” replied Tim. “If you were to see the way he lets the Turks run over his back, when he’s wounded in Timour the Tartar, you wouldn’t believe he was a livin’ baste.”

“Poor fellow!” said I, caressing him. He turned his mild eye upon me, and we were friends from that hour.

What a glorious morning it was, as I gained the outskirts of the city, and entered one of those shady alleys that lead to the foot of the Dublin mountains! The birds were opening their morning hymn, and the earth, still fresh from the night dew, sent up a thousand delicious perfumes. The road on either side was one succession of handsome villas or ornamental cottages, whose grounds were laid out in the perfection of landscape gardening. There were but few persons to be seen at that early hour, and in the smokeless chimneys and closed shutters I could read that all slept,—slept in that luxurious hour when Nature unveils, and seems to revel in the sense of unregarded loveliness. “Ah, Potts,” said I, “thou hast chosen the wiser part; thou wilt see the world after thine own guise, and not as others see it.” Has my reader not often noticed that in a picture-gallery the slightest change of place, a move to the left or right, a chance approach or retreat, suffices to make what seemed a hazy confusion of color and gloss a rich and beautiful picture? So is it in the actual world, and just as much depends on the point from which objects are viewed. Do not be discouraged, then, by the dark aspects of events. It may be that by the slightest move to this side or to that, some unlooked-for sunlight shall slant down and light up all the scene. Thus musing, I gained a little grassy strip that ran along the roadside, and, gently touching Blonde! with my heel, he broke out into a delightful canter. The motion, so easy and swimming, made it a perfect ecstasy to sit there floating at will through the thin air, with a moving panorama of wood, water, and mountain around me.

Emerging at length from the thickly wooded plain, I began the ascent of the Three Rock Mountain, and, in my slackened speed, had full time to gaze upon the bay beneath me, broken with many a promontory, backed by the broad bluff of Howth, and the more distant Lambay. No, it is not finer than Naples. I did not say it was; but, seeing it as I then saw it, I thought it could not be surpassed. Indeed, I went further, and defied Naples in this fashion:—

“Though no volcano’s lurid light Over thy bine sea steals along, Nor Pescator beguiles the night With cadence of his simple song; “Though none of dark Calabria’s daughters With tinkling lute thy echoes wake, Mingling their voices with the waters, As ‘neath the prow the ripples break; “Although no cliffs with myrtle crown’d, Reflected in thy tide, are seen, Nor olives, bending to the ground, Relieve the laurel’s darker green; “Yet—yet—”

Ah, there was the difficulty,—I had begun with the plaintiff, and I really had n’t a word to say for the defendant; and so, voting comparisons odious, I set forward on my journey.

As I rode into Enniskerry to breakfast, I had the satisfaction of overhearing some very flattering comments upon Blondel, which rather consoled me for some less laudatory remarks upon my own horsemanship. By the way, can there possibly be a more ignorant sarcasm than to say a man rides like a tailor? Why, of all trades, who so constantly sits straddle-legged as a tailor? and yet he is especial mark of this impertinence.

I pushed briskly on after breakfast, and soon found myself in the deep shady woods that lead to the Dargle. I hurried through the picturesque demesne, associated as it was with a thousand little vulgar incidents of city junketings, and rode on for the Glen of the Downs. Blondel and I had now established a most admirable understanding with each other. It was a sort of reciprocity by which I bound myself never to control him, he in turn consenting not to unseat me. He gave the initiative to the system, by setting off at his pleasant little rocking canter whenever he chanced upon a bit of favorable ground, and invariably pulled up when the road was stony or uneven; thus showing me that he was a beast with what Lord Brougham would call “a wise discretion.” In like manner he would halt to pluck any stray ears of wild oats that grew along the hedge sides, and occasionally slake his thirst at convenient streamlets. If I dismounted to walk at his side, he moved along unheld, his head almost touching my elbow, and his plaintive blue eye mildly beaming on me with an expression that almost spoke,—nay, it did speak. I ‘m sure I felt it, as though I could swear to it, whispering, “Yes, Potts, two more friendless creatures than ourselves are not easy to find. The world wants not either of us; not that we abuse it, despise it, or treat it ungenerously,—rather the reverse, we incline favorably towards it, and would, occasion serving, befriend it; but we are not, so to say, ‘of it.’ There may be, here and there, a man or a horse that would understand or appreciate us, but they stand alone,—they are not belonging to classes. They are, like ourselves, exceptional.” If his expression said this much, there was much unspoken melancholy in his sad glance, also, which seemed to say, “What a deal of sorrow could I reveal if I might!—what injuries, what wrong, what cruel misconceptions of my nature and disposition, what mistaken notions of my character and intentions! What pretentious stupidity, too, have I seen preferred before me,—creatures with, mayhap, a glossier coat or a more silky forelock—” “Ah, Blondel, take courage,—men are just as ungenerous, just as erring!” “Not that I have not had my triumphs, too,” he seemed to say, as, cocking his ears, and ambling with a more elevated toss of the head, his tail would describe an arch like a waterfall; “no salmon-colored silk stockings danced sarabands on my back; I was always ridden in the Haute École by Monsieur l’Etrier himself, the stately gentleman in jackboots and long-waisted dress-coat, whose five minutes no persuasive bravos could ever prolong.” I thought—nay, I was certain at times—that I could read in his thoughtful face the painful sorrows of one who had outlived popular favor, and who had survived to see himself supplanted and dethroned.

There are no two destinies which chime in so well together as that of him who is beaten down by sheer distrust of himself, and that of the man who has seen better days. Although the one be just entering on life, while the other is going out of it, if they meet on the threshold, they stop to form a friendship. Now, though Blondel was not a man, he supplied to my friendlessness the place of one.

The sun was near its setting, as I rode down the little hill into the village of Ashford, a picturesque little spot in the midst of mountains, and with a bright clear stream bounding through it, as fearlessly as though in all the liberty of open country. I tried to make my entrance what stage people call effective. I threw myself, albeit a little jaded, into an attitude of easy indifference, slouched my hat to one side, and suffered the sprig of laburnum, with which I had adorned it, to droop in graceful guise over one shoulder. The villagers stared; some saluted me; and taken, perhaps, by the cool acquiescence of my manner, as I returned the courtesy, seemed well disposed to believe me of some note.

I rode into the little stable-yard of the “Lamb” and dismounted. I gave up my horse, and walked into the inn. I don’t know how others feel it,—I greatly doubt if they will have the honesty to tell,—but for myself, I confess that I never entered an inn or an hotel without a most uncomfortable conflict within: a struggle made up of two very antagonistic impulses,—the wish to seem something important, and a lively terror lest the pretence should turn out to be costly. Thus swayed by opposing motives, I sought a compromise by assuming that I was incog.; for the present a nobody, to be treated without any marked attention, and to whom the acme of respect would be a seeming indifference.

“What is your village called?” I said, carelessly, to the waiter, as he laid the cloth.

“Ashford, your honor. ‘T is down in all the books,” answered the waiter.

“Is it noted for anything, or is there anything remarkable in the neighborhood?”

“Indeed, there is, sir, and plenty. There’s Glenmalure and the Devil’s Glen; and there’s Mr. Snow Malone’s place, that everybody goes to see: and there’s the fishing of Doyle’s river,—trout, eight, nine, maybe twelve, pounds’ weight; and there’s Mr. Reeve’s cottage—a Swiss cottage belike—at Kinmacreedy; but, to be sure, there must be an order for that!”

“I never take much trouble,” I said indolently. “Who have you got in the house at present?”

“There’s young Lord Keldrum, sir, and two more with him, for the fishing; and the next room to you here, there’s Father Dyke, from Inistioge, and he’s going, by the same token, to dine with the Lord to-day.”

“Don’t mention to his Lordship that I am here,” said I, hastily. “I desire to be quite unknown down here.” The waiter promised obedience, without vouchsafing any misgivings as to the possibility of his disclosing what he did not know.

To his question as to my dinner, I carelessly said, as if I were in a West-end club, “Never mind soup,—a little fish,—a cutlet and a partridge. Or order it yourself,—I am indifferent.” The waiter had scarcely left the room when I was startled by the sound of voices so close to me as to seem at my side. They came from a little wooden balcony to the adjoining room, which, by its pretentious bow-window, I recognized to be the state apartment of the inn, and now in the possession of Lord Keldrum and his party. They were talking away in that gay, rattling, discursive fashion very young men do amongst each other, and discussed fishing-flies, the neighboring gentlemen’s seats, and the landlady’s niece.

“By the way, Kel,” cried one, “it was in your visit to the bar that you met your priest, was n’t it?”

“Yes; I offered him a cigar, and we began to chat together, and so I asked him to dine with us to-day.”

“And he refused?”

“Yes; but he has since changed his mind, and sent a message to say he ‘ll be with us at eight”.

“I should like to see your father’s face, Kel, when he heard of your entertaining the Reverend Father Dyke at dinner.”

“Well, I suppose he would say it was carrying conciliation a little too far; but as the adage says, À la guerre—”

At this juncture, another burst in amongst them, calling out, “You ‘d never guess who ‘s just arrived here, in strict incog., and having bribed Mike, the waiter, to silence. Burgoyne!”

“Not Jack Burgoyne?”

“Jack himself. I had the portrait so correctly drawn by the waiter, that there’s no mistaking him; the long hair, green complexion, sheepish look, all perfect. He came on a hack, a little cream-colored pad he got at Dycer’s, and fancies he’s quite unknown.”

“What can he be up to now?”

“I think I have it,” said his Lordship. “Courtenay has got two three-year-olds down here at his uncle’s, one of them under heavy engagements for the spring meetings. Master Jack has taken a run down to have a look at them.”

“By Jove, Kel, you ‘re right! he’s always wide awake, and that stupid leaden-eyed look he has, has done him good service in the world.”

“I say, old Oxley, shall we dash in and unearth him? Or shall we let him fancy that we know nothing of his being here at all?”

“What does Hammond say?”

“I’d say, leave him to himself,” replied a deep voice; “you can’t go and see him without asking him to dinner; and he ‘ll walk into us after, do what we will.”

“Not, surely, if we don’t play,” said Oxley.

“Would n’t he, though? Why, he ‘d screw a bet out of a bishop.”

“I ‘d do with him as Tomkinson did,” said his Lordship; “he had him down at his lodge in Scotland, and bet him fifty pounds that he could n’t pass a week without a wager. Jack booked the bet and won it, and Tomkinson franked the company.”

“What an artful villain my counterpart must be!” I said. I stared in the glass to see if I could discover the sheepish-ness they laid such stress on. I was pale, to be sure, and my hair a light brown, but so was Shelley’s; indeed, there was a wild, but soft expression in my eyes that resembled his, and I could recognize many things in our natures that seemed to correspond. It was the poetic dreaminess, the lofty abstractedness from all the petty cares of every-day life which vulgar people set down as simplicity; and thus,—

“The soaring thoughts that reached the stare, Seemed ignorance to them.”

As I uttered the consolatory lines, I felt two hands firmly pressed over my eyes, while a friendly voice called out, “Found out, old fellow! run fairly to earth!” “Ask him if he knows you,” whispered another, but in a voice I could catch.

“Who am I, Jack?” cried the first speaker.

“Situated as I now am,” I replied, “I am unable to pronounce; but of one thing I am assured,—I am certain I am not called Jack.”

The slow and measured intonation of my voice seemed to electrify them, for my captor relinquished his hold and fell back, while the two others, after a few seconds of blank surprise, burst into a roar of laughter; a sentiment which the other could not refrain from, while he struggled to mutter some words of apology.

“Perhaps I can explain your mistake,” I said blandly; “I am supposed to be extremely like the Prince of Salms Hökinshauven—”

“No, no!” burst in Lord Keldrum, whose voice I recognized, “we never saw the Prince. The blunder of the waiter led us into this embarrassment; we fancied you were—”

“Mr. Burgoyne,” I chimed in.

“Exactly,—Jack Burgoyne; but you’re not a bit like him.”

“Strange, then; but I’m constantly mistaken for him; and when in London, I 'm actually persecuted by people calling out, ‘When did you come up, Jack?’ ‘Where do you hang out?’ ‘How long do you stay?’ ‘Dine with me to-day—to-morrow—Saturday?’ and so on; and although, as I have remarked, these are only so many embarrassments for me, they all show how popular must be my prototype.” I had purposely made this speech of mine a little long, for I saw by the disconcerted looks of the party that they did not see how to wind up “the situation,” and, like all awkward men, I grew garrulous where I ought to have been silent. While I rambled on, Lord Keldrum exchanged a word or two with one of his friends; and as I finished, he turned towards me, and, with an air of much courtesy, said,—

“We owe you every apology for this intrusion, and hope you will pardon it; there is, however, but one way in which we can certainly feel assured that we have your forgiveness,—that is, by your joining us. I see that your dinner is in preparation, so pray let me countermand it, and say that you are our guest.”

“Lord Keldrum,” said one of the party, presenting the speaker; “my name is Hammond, and this is Captain Oxley, Coldstream Guards.”

I saw that this move required an exchange of ratifications, and so I bowed, and said, “Algernon Sydney Potts.”

“There are Staffordshire Pottses?”

“No relation,” I said stiffly. It was Hammond who made the remark, and with a sneering manner that I could not abide.

“Well, Mr. Potts, it is agreed,” said Lord Keldrum, with his peculiar urbanity, “we shall see you at eight No dressing. You’ll find us in this fishing-costume you see now.”

I trust my reader, who has dined out any day he pleased and in any society he has liked these years past, will forgive me if I do not enter into any detailed account of my reasons for accepting this invitation. Enough if I freely own that to me, A. S. Potts, such an unexpected honor was about the same surprise as if I had been announced governor of a colony, or bishop in a new settlement.

“At eight sharp, Mr. Potts.”

“The next door down the passage.”

“Just as you are, remember!” were the three parting admonitions with which they left me.

Who has not experienced the charm of the first time in his life, when totally removed from all the accidents of his station, the circumstance of his fortune, and his other belongings, he has taken his place amongst perfect strangers, and been estimated by the claims of his own individuality? Is it not this which gives the almost ecstasy of our first tour,—our first journey? There are none to say, “Who is this Potts that gives himself these airs?” “What pretension has he to say this, or order that?” “What would old Peter say if he saw his son to-day?” with all the other “What has the world come tos?” and “What are we to see nexts?” I say it is with a glorious sense of independence that one sees himself emancipated from all these restraints, and recognizes his freedom to be that which nature has made him.

As I sat on Lord Keldrum’s left,—Father Dyke was on his right,—was I in any real quality other than I ever am? Was my nature different, my voice, my manner, my social tone, as I received all the bland attentions of my courteous host? And yet, in my heart of hearts, I felt that if it were known to that polite company I was the son of Peter Potts, 'pothecary, all my conversational courage would have failed me. I would not have dared to assert fifty things I now declared, nor vouched for a hundred that I as assuredly guaranteed. If I had had to carry about me traditions of the shop in Mary’s Abbey, the laboratory, and the rest of it, how could I have had the nerve to discuss any of the topics on which I now pronounced so authoritatively? And yet, these were all accidents of my existence,—no more me than was the color of his whiskers mine who vaccinated me for cow-pock. The man Potts was himself through all; he was neither compounded of senna and salts, nor amalgamated with sarsaparilla and the acids; but by the cruel laws of a harsh conventionality it was decreed otherwise, and the trade of the father descends to the son in every estimate of all he does and says and thinks. The converse of the proposition I was now to feel in the success I obtained in this company. I was as the Germans would say, “Der Herr Potts selbst, nicht nach seinen Begebenheiten”—the man Potts, not the creature of his belongings.

The man thus freed from his “antecedents,” and owning no “relatives,” feels like one to whom a great, a most unlimited, credit has been opened, in matter of opinion. Not reduced to fashion his sentiments by some supposed standard becoming his station, he roams at will over the broad prairie of life, enough if he can show cause why he says this or thinks that, without having to defend himself for his parentage, and the place he was born in. Little wonder if, with such a sum to my credit, I drew largely on it; little wonder if I were dogmatical and demonstrative; little wonder if, when my reason grew wearied with facts, I reposed on my imagination in fiction.

Be it remembered, however, that I only became what I have set down here after an excellent dinner, a considerable quantity of champagne, and no small share of claret, strong-bodied enough to please the priest. From the moment we sat down to table, I conceived for him a sort of distrust. He was painfully polite and civil; he had a soft, slippery, Clare accent; but there was a malicious twinkle in his eye that showed he was by nature satirical. Perhaps because we were more reading men than the others that it was we soon found ourselves pitted against each other in argument, and this not upon one, but upon every possible topic that turned up. Hammond, I found, also stood by the priest; Oxley was my backer; and his Lordship played umpire. Dyke was a shrewd, sarcastic dog in his way, but he had no chance with me. How mercilessly I treated his church!—he pushed me to it,—what an exposé did I make of the Pope and his government, with all their extortions and cruelties! how ruthlessly I showed them up as the sworn enemies of all freedom and enlightenment! The priest never got angry. He was too cunning for that, and he even laughed at some of my anecdotes, of which I related a great many.

“Don’t be so hard on him, Potts,” whispered my Lord, as the day wore on; “he ‘s not one of us, you know!”

This speech put me into a flutter of delight. It was not alone that he called me Potts, but there was also an acceptance of me as one of hier own set. We were, in fact, henceforth nous autres. Enchanting recognition, never to be forgotten!

“But what would you do with us?” said Dyke, mildly remonstrating against some severe measures we of the landed interest might be yet driven to resort to.

“I don’t know,—that is to say,—I have not made up my mind whether it were better to make a clearance of you altogether, or to bribe you.”

“Bribe us by all means, then!” said he, with a most serious earnestness.

“Ah! but could we rely upon you?” I asked.

“That would greatly depend upon the price.”

“I ‘ll not haggle about terms, nor I ‘m sure would Keldrum,” said I, nodding over to his Lordship.

“You are only just to me, in that,” said he, smiling.

“That’s all fine talking for you fellows who had the luck to be first on the list, but what are poor devils like Oxley and myself to do?” said Hammond. “Taxation comes down to second sons.”

“And the ‘Times’ says that’s all right,” added Oxley.

“And I say it’s all wrong; and I say more,” I broke in: “I say that of all the tyrannies of Europe, I know of none like that newspaper. Why, sir, whose station, I would ask, nowadays, can exempt him from its impertinent criticisms? Can Keldrum say—can I say—that to-morrow or next day we shall not be arraigned for this, that, or t’other? I choose, for instance, to manage my estate,—the property that has been in my family for centuries,—the acres that have descended to us by grants as old as Magna Charta. I desire, for reasons that seem sufficient to myself, to convert arable into grass land. I say to one of my tenant farmers—it’s Hedgeworth—no matter, I shall not mention names, but I say to him—”

“I know the man,” broke in the priest; “you mean Hedgeworth Davis, of Mount Davis.”

“No, sir, I do not,” said I, angrily, for I resented this attempt to run me to earth.

“Hedgeworth! Hedgeworth! It ain’t that fellow that was in the Rifles; the 2d battalion, is it?” said Ozley.

“I repeat,” said I, “that I will mention no names.”

“My mother had some relatives Hedgeworths, they were from Herefordshire. How odd, Potts, if we should turn out to be connections! You said that these people were related to you.”

“I hope,” I said angrily, “that I am not bound to give the birth, parentage, and education of every man whose name I may mention in conversation. At least, I would protest that I have not prepared myself for such a demand upon my memory.”

“Of course not, Potts. It would be a test no man could submit to,” said his Lordship.

“That Hedgeworth, who was in the Rifles, exceeded all the fellows I ever met in drawing the long bow. There was no country he had not been in, no army he had not served with; he was related to every celebrated man in Europe; and, after all, it turned out that his father was an attorney at Market Harborough, and sub-agent to one of our fellows who had some property there.” This was said by Hammond, who directed the speech entirely to me.

“Confound the Hedgeworths, all together,” Ozley broke in. “They have carried us miles away from what we were talking of.”

This was a sentiment that met my heartiest concurrence, and I nodded in friendly recognition to the speaker, and drank off my glass to his health.

“Who can give us a song? I ‘ll back his reverence here to be a vocalist,” cried Hammond. And sure enough, Dyke sang one of the national melodies with great feeling and taste. Ozley followed with something in less perfect taste, and we all grew very jolly. Then there came a broiled bone and some devilled kidneys, and a warm brew which Hammond himself concocted,—a most insidious liquor, which had a strong odor of lemons, and was compounded, at the same time, of little else than rum and sugar.

There is an adage that says “in vino Veritas,” which I shrewdly suspect to be a great fallacy; at least, as regards my own case, I know it to be totally inapplicable. I am in my sober hours—and I am proud to say that the exceptions from such are of the rarest—one of the most veracious of mortals; indeed, in my frank sincerity, I have often given offence to those who like a courteous hypocrisy better than an ungraceful truth. Whenever by any chance it has been my ill-fortune to transgress these limits, there is no bound to my imagination. There is nothing too extravagant or too vainglorious for me to say of myself. All the strange incidents of romance that I have read, all the travellers’ stories, newspaper accidents, adventures by sea and land, wonderful coincidences, unexpected turns of fortune, I adapt to myself, and coolly relate them as personal experiences. Listeners have afterwards told me that I possess an amount of consistence, a verisimilitude in these narratives perfectly marvellous, and only to be accounted for by supposing that I myself must, for the time being, be the dupe of my own imagination. Indeed, I am sure such must be the true explanation of this curious fact. How, in any other mode, explain the rash wagers, absurd and impossible engagements I have contracted in such moments, backing myself to leap twenty-three feet on the level sward; to dive in six fathoms water, and fetch up Heaven knows what of shells and marine curiosities from the bottom; to ride the most unmanageable of horses; and, single-handed and unarmed, to fight the fiercest bulldog in England? Then, as to intellectual feats, what have I not engaged to perform? Sums of mental arithmetic; whole newspapers committed to memory after one reading; verse compositions, on any theme, in ten languages; and once a written contract to compose a whole opera, with all the scores, within twenty-four hours. To a nature thus strangely constituted, wine was a perfect magic wand, transforming a poor, weak, distrustful modest man into a hero; and yet, even with such temptations, my excesses were extremely rare and unfrequent. Are there many, I would ask, that could resist the passport to such a dreamland, with only the penalty of a headache the next morning? Some one would, perhaps, suggest that these were enjoyments to pay forfeit on. Well, so they were; but I must not anticipate. And now to my tale.

To Hammond’s brew there succeeded one by Oxley, made after an American receipt, and certainly both fragrant and insinuating; and then came a concoction made by the priest, which he called “Father Hosey’s pride.” It was made in a bowl, and drunk out of lemon-rinds, ingeniously fitted into the wine-glasses. I remember no other particulars about it, though I can call to mind much of the conversation that preceded it. How I gave a long historical account of my family, that we came originally from Corsica, the name Potts being a corruption of Pozzo, and that we were of the same stock as the celebrated diplomatist Pozzo di Borgo. Our unclaimed estates in the island were of fabulous value, but in asserting my right to them I should accept thirteen mortal duels, the arrears of a hundred and odd years un-scored off, in anticipation of which I had at one time taken lessons from Angelo, in fencing, which led to the celebrated challenge they might have read in “Galignani,” where I offered to meet any swordsman in Europe for ten thousand Napoleons, giving choice of the weapon to my adversary. With a tear to the memory of the poor French colonel that I killed at Sedan, I turned the conversation. Being in France, I incidentally mentioned some anecdotes of military life, and bow I had invented the rifle called after Minié’s name, and, in a moment of good nature, given that excellent fellow my secret.

“I will say,” said I, “that Minié has shown more gratitude than some others nearer home, but we ‘ll talk of rifled cannon another time.”

In an episode about bear-shooting, I mentioned the Emperor of Russia, poor dear Nicholas, and told how we had once exchanged horses,—mine being more strong-boned, and a weight-carrier; his a light Caucasian mare of purest breed, “the dam of that creature you may see below in the stable now,” said I, carelessly. “‘Come and see me one of these days, Potts,’ said he, in parting; ‘come and pass a week with me at Constantinople.’ This was the first intimation he had ever given of his project against Turkey; and when I told it to the Duke of Wellington, his remark was a muttered ‘Strange fellow, Potts,—knows everything!’ though he made no reply to me at the time.”

It was somewhere about this period that the priest began with what struck me as an attempt to outdo me as a storyteller, an effort I should have treated with the most contemptuous indifference but for the amount of attention bestowed on him by the others. Nor was this all, but actually I perceived that a kind of rivalry was attempted to be established, so that we were pitted directly against each other. Amongst the other self-delusions of such moments was the profound conviction I entertained that I was master of all games of skill and address, superior to Major A. at whist, and able to give Staunton a pawn and the move at chess. The priest was just as vainglorious. “He’d like to see the man who ‘d play him a game of ‘spoiled five’”—whatever that was—“or drafts; ay, or, though it was not his pride, a bit of backgammon.”

“Done, for fifty pounds; double on the gammon!” cried I.

“Fifty fiddlesticks!” cried he; “where would you or I find as many shillings?”

“What do you mean, sir?” said I, angrily. “Am I to suppose that you doubt my competence to risk such a comtemptible sum, or is it to your own inability alone you would testify?”

A very acrimonious dispute followed, of which I have no clear recollection. I only remember how Hammond was out-and out for the priest, and Oxley too tipsy to take my part with any efficiency. At last—Row arranged I can’t say—peace was restored, and the next thing I can recall was listening to Father Dyke giving a long, and of course a most fabulous, history of a ring that he wore on his second finger. It was given by the Pretender, he said, to his uncle, the celebrated Carmelite monk, Lawrence O’Kelly, who for years bad followed the young prince’s fortunes. It was an onyx, with the letters C. E. S. engraved on it. Keldrum took an immense fancy to it; he protested that everything that attached to that unhappy family possessed in his eyes an uncommon interest. “If you have a fancy to take up Potto’s wager,” said he, laughingly, “I’ll give you fifty pounds for your signet ring.”

The priest demurred; Hammond interposed; then there was more discussion, now warm, now jocose. Oxley tried to suggest something, which we all laughed at. Keldrum placed the backgammon board meanwhile; but I can give no clear account of what ensued, though I remember that the terms of our wager were committed to writing by Hammond, and signed by Father D. and myself, and in the conditions there figured a certain ring, guaranteed to have belonged to and been worn by his Royal Highness Charles Edward, and a cream-colored horse, equally guaranteed as the produce of a Caucasian mare presented by the late Emperor Nicholas to the present owner. The document was witnessed by all three, Oxley’s name written in two letters, and a flourish. After that, I played, and lost!

I can recall to this very hour the sensations of headache and misery with which I awoke the morning after this debauch. Backing pain it was, with a sort of tremulous beating all through the brain, as though a small engine had been set to work there, and that piston and boiler and connecting-rod were all banging, fizzing, and vibrating amid my fevered senses. I was, besides, much puzzled to know where I was, and how I had come there. Controversial divinity, genealogy, horse-racing, the peerage, and “double sixes” were dancing a wild cotillon through my brain; and although a waiter more than once cautiously obtruded his head into the room, to see if I were asleep, and as guardedly withdrew it again, I never had energy to speak to him, but lay passive and still, waiting till my mind might clear, and the cloud-fog that obscured my faculties might be wafted away.

At last—it was towards evening—the man, possibly becoming alarmed at my protracted lethargy, moved somewhat briskly through the room, and with that amount of noise that showed he meant to arouse me, disturbed chairs and fire-irons indiscriminately.

“Is it late or early?” asked I, faintly.

“Tis near five, sir, and a beautiful evening,” said he, drawing nigh, with the air of one disposed for colloquy.

I did n’t exactly like to ask where I was, and tried to ascertain the fact by a little circumlocution. “I suppose,” said I, yawning, “for all that is to be done in a place like this, when up, one might just as well stay abed, eh?”

“T is the snuggest place, anyhow,” said he, with that peculiar disposition to agree with you so characteristic in an Irish waiter.

“No society?” sighed I.

“No, indeed, sir.”

“No theatre?”

“Devil a one, sir.”

“No sport?”

“Yesterday was the last of the season, sir; and signs on it, his Lordship and the other gentleman was off immediately after breakfast.”

“You mean Lord—Lord—” A mist was clearing slowly away, but I could not yet see clearly.

“Lord Keldrum, sir; a real gentleman every inch of him.”

“Oh! yes, to be sure,—a very old friend of mine,” muttered I. “And so he’s gone, is he?”

“Yes, sir; and the last word he said was about your honor.”

“About me,—what was it?”

“Well, indeed, sir,” replied the waiter, with a hesitating and confused manner, “I did n’t rightly understand it; but as well as I could catch the words, it was something about hoping your honor had more of that wonderful breed of horses the Emperor of Roosia gave you.”

“Oh, yes! I understand,” said I, stopping him abruptly. “By the way, how is Blondel—that is, my horse—this morning?”

“Well, he looked fresh and hearty, when he went off this morning at daybreak—”

“What do you mean?” cried I, jumping up in my bed. “Went off? where to?”

“With Father Dyke on his back; and a neater hand he could n’t wish over him. ‘Tim,’ says he, to the ostler, as he mounted, ‘there’s a five-shilling piece for you, for hansel, for I won this baste last night, and you must drink my health and wish me luck with him.’”

I heard no more, but, sinking back into the bed, I covered my face with my hands, overcome with shame and misery. All the mists that had blurred my faculties had now been swept clean away, and the whole history of the previous evening was revealed before me. My stupid folly, my absurd boastfulness, my egregious story-telling,—not to call it worse,—were all there; but, shall I acknowledge it? what pained me not less poignantly was the fact that I ventured to stake the horse I had merely hired, and actually lost him at the play-table.

As soon as I rallied from this state of self-accusation, I set to work to think how I should manage to repossess myself of my beast, my loss of which might be converted into a felony. To follow the priest and ransom Blondel was my first care. Father Dyke would most probably not exact an unreasonable price; he, of course, never believed one word of my nonsensical narrative about Schamyl and the Caucasus, and he ‘d not revenge upon Potts sober the follies of Potts tipsy. It is true my purse was a very slender one, but Blondel, to any one unacquainted with his pedigree, could not be a costly animal; fifteen pounds—twenty, certainly—ought to buy what the priest would call “every hair on his tail.”

It was now too late in the evening to proceed to execute the measures I had resolved on, and so I determined to lie still and ponder over them. Dismissing the waiter, with an order to bring me a cup of tea about eight o’clock, I resumed my cogitations. They were not pleasant ones: Potts a byword for the most outrageous and incoherent balderdash and untruth; Potts in the “Hue and Cry;” Potts in the dock; Potts in the pillory; Potts paragraphed in “Punch;” portrait of Potts, price one penny!—these were only a few of the forms in which the descendant of the famous Corsican family of Pozzo di Borgo now presented himself to my imagination.

The courts and quadrangles of Old Trinity ringing with laughter, the coarse exaggerations of tasteless scoffers, the jokes and sneers of stupidity, malice, and all uncharitableness, rang in my ears as if I heard them. All possible and impossible versions of the incident passed in review before me: my father, driven distracted by impertinent inquiries, cutting me off with a shilling, and then dying of mortification and chagrin; rewards offered for my apprehension; descriptions, not in any way flatteries, of my personal appearance; paragraphs of local papers hinting that the notorious Potts was supposed to have been seen in our neighborhood yesterday, with sly suggestions about looking after stable-doors, &c. I could bear it no longer. I jumped up, and rang the bell violently.

“You know this Father Dyke, waiter? In what part of the country does he live?”

“He’s parish priest of Inistioge,” said he; “the snuggest place in the whole county.”

“How far from this may it be?”

“It’s a matter of five-and-forty miles; and by the same token, he said he 'd not draw bridle till he got home to-night, for there was a fair at Grague to-morrow, and if he was n’t pleased with the baste he ‘d sell him there.”

I groaned deeply; for here was a new complication, entirely unlooked for. “You can’t possibly mean,” gasped I out, “that a respectable clergyman would expose for sale a horse lent to him casually by a friend?” for the thought struck me that this protest of mine should be thus early on record.

The waiter scratched his head and looked confused. Whether another version of the event possessed him, or that my question staggered his convictions, I am unable to say; but he made no reply. “It is true,” continued I, in the same strain, “that I met his reverence last night for the first time. My friend Lord Keldrum made us acquainted; but seeing him received at my noble friend’s board, I naturally felt, and said to myself, ‘The man Keldrum admits to his table is the equal of any one.’ Could anything be more reasonable than that?”

“No, indeed, sir; nothing,” said the waiter, obsequiously.

“Well, then,” resumed I, “some day or other it may chance that you will be called on to remember and recall this conversation between us; if so, it will be important that you should have a clear and distinct memory of the fact that when I awoke in the morning, and asked for my horse, the answer you made me was—What was the answer you made me?”

“The answer I med was this,” said the fellow, sturdily, and with an effrontery I can never forget,—“the answer I med was, that the man that won him took him away.”

“You’re an insolent scoundrel,” cried I, boiling over with passion, “and if you don’t ask pardon for this outrage on your knees, I ‘ll include you in the indictment for conspiracy.”

So far from proceeding to the penitential act I proposed, the fellow grinned from ear to ear, and left the room. It was a long time before I could recover my wonted calm and composure. That this rascal’s evidence would be fatal to me if the question ever came to trial, was as clear as noonday; not less clear was it that he knew this himself.

“I must go back at once to town,” thought I. “I will surrender myself to the law. If a compromise be impossible, I will perish at the stake.”

I forgot there was no stake; but there was wool-carding, and oakum-picking, and wheel-treading, and oyster-shell pounding, and other small plays of this nature, infinitely more degrading to humanity than all the cruelties of our barbarous ancestors.

Now, in no record of lives of adventure had I met any account of such trials as these. The Silvio Pellicos of Pentonville are yet unwritten martyrs. Prison discipline would vulgarize the grandest epic that ever was conceived “Anything rather than this,” said I, aloud. “Proscribed, outlawed, hunted down, but never, gray-coated and hair-clipped, shall a Potts be sentenced to the ‘crank,’ or black-holed as refractory!—Bring me my bill,” cried I, in a voice of indignant anger. “I will go forth into the world of darkness and tempest; I will meet the storm and the hurricane; better all the conflict of the elements than man’s—than man’s—” I was n’t exactly sure what; but there was no need of the word, for a gust of wind had just flattened my umbrella in my face as I issued forth, and left me breathless, as the door closed behind me.

As I walked onward against the swooping wind and the plashing rain, I felt a sort of heroic ardor in the notion of breasting the adverse waves of life so boldly. It is not every fellow could do this,—throw his knapsack on his shoulder, seize his stick, and set out in storm and blackness. No, Potts, my man; for downright inflexibility of purpose, for bold and resolute action, you need yield to none! It was, indeed, an awful night; the thunder rolled and crashed with scarce an interval of cessation; forked lightning tore across the sky in every direction; while the wind swept through the deep glen, smashing branches and uplifting large trees like mere shrubs. I was soon completely drenched, and my soaked clothes hung around with the weight of lead; my spirits, however, sustained me, and I toiled along, occasionally in a sort of wild bravado, giving a cheer as the thunder rolled close above my head, and trying to sing, as though my heart were as gay and my spirits as light as in an hour of happiest abandonment.

Jean Paul has somewhere the theory that our Good Genius is attached to us from our birth by a film fine as gossamer, and which few of us escape rupturing in the first years of youth, thus throwing ourselves at once without chart or pilot upon the broad ocean of life. He, however, more happily constituted, who feels the guidance of his guardian spirit, recognizes the benefits of its care, and the admonitions of its wisdom,—he is destined to great things. Such men discover new worlds beyond the seas, carry conquest over millions, found dynasties, and build up empires; they whom the world regard as demigods having simply the wisdom of being led by fortune, and not severing the slender thread that unites them to their destiny. Was I, Potts, in this glorious category? Had the lesson of the great moralist been such a warning to me that I had preserved the filmy link unbroken? I really began to think so; a certain impulse, a whispering voice within, that said, “Go on!” On, ever onward! seemed to be the accents of that Fate which had great things in store for me, and would eventually make me illustrious.

No illusions of your own, Potts, no phantasmagoria of your own poor heated fancy, must wile you away from the great and noble part destined for you. No weakness, no faint-heartedness, no shrinking from toil, nor even peril. Work hard to know thoroughly for what Fate intends you; read your credentials well, and then go to your post unflinchingly. Revolving this theory of mine, I walked ever on. It opened a wide field, and my imagination disported in it, as might a wild mustang over some vast prairie. The more I thought over it, the more did it seem to me the real embodiment of that superstition which extends to every land and every family of men. We are Lucky when, submitting to our Good Genius, we suffer ourselves to be led along unhesitatingly; we are Unlucky when, breaking our frail bonds, we encounter life unguided and unaided.

What a docile, obedient, and believing pupil did I pledge myself to be! Fate should see that she had no refractory nor rebellious spirit in me, no self-indulgent voluptuary, seeking only the sunny side of existence, but a nature ready to confront the rugged conflict of life, and to meet its hardships, if such were my allotted path.

I applied the circumstances in which I then found myself to my theory, and met no difficulty in the adaptation. Blondel was to perform a great part in my future. Blondel was a symbol selected by fate to indicate a certain direction. Blondel was a lamp by which I could find my way in the dark paths of the world. With Blondel, my Good Genius would walk beside me, or occasionally get up on the crupper, but never leave me or desert me. In the high excitement of my mind, I felt no sense of bodily fatigue, but walked on, drenched to the skin, alternately shivering with cold or burning with all the intensity of fever. In this state was it that I entered the little inn of Ovoco soon after daybreak, and stood dripping in the bar, a sad spectacle of exhaustion and excitement My first question was, “Has Blondel been here?” and before they could reply, I went on with all the rapidity of delirium to assure them that deception of me would be fruitless; that Fate and I understood each other thoroughly, travelled together on the best of terms, never disagreed about anything, but, by a mutual system of give and take, hit it off like brothers. I talked for an hour in this strain; and then my poor faculties, long struggling and sore pushed, gave way completely, and I fell into brain fever.

I chanced upon kind and good-hearted folk, who nursed me with care and watched me with interest; but my illness was a severe one, and it was only in the sixth week that I could be about again, a poor, weak, emaciated creature, with failing limbs and shattered nerves. There is an indescribable sense of weariness in the mind after fever, just as if the brain had been enormously over-taxed and exerted, and that in the pursuit of all the wild and fleeting fancies of delirium it had travelled over miles and miles of space. To the depressing influence of this sensation is added the difficulty of disentangling the capricious illusions of the sick-bed from the actual facts of life; and in this maze of confusion my first days of convalescence were passed. Blondel was my great puzzle. Was he a reality, or a mere creature of imagination? Had I really ridden him as a horse, or only as an idea? Was he a quadruped with mane and tail, or an allegory invented to typify destiny? I cannot say what hours of painful brain labor this inquiry cost me, and what intense research into myself. Strange enough, too, though I came out of the investigation convinced of his existence, I arrived at the conclusion that he was a “horse and something more.” Not that I am able to explain myself more fully on that head, though, if I were writing this portion of my memoirs in German, I suspect I could convey enough of my meaning to give a bad headache to any one indulgent enough to follow me.

I set out once more upon my pilgrimage on a fine day of June, my steps directed to the village of Inistioge, where Father Dyke resided. I was too weak for much exertion, and it was only after five days of the road I reached at nightfall the little glen in which the village stood. The moon was up, streaking the wide market-places with long lines of yellow light between the rows of tall elm-trees, and tipping with silvery sheen the bright eddies of the beautiful river that rolled beside it. Over the granite cliffs that margined the stream, laurel, and arbutus, and wild holly clustered in wild luxuriance, backed higher up again, by tall pine-trees, whose leafy summits stood out against the sky; and lastly, deep within a waving meadow, stood an old ruined abbey, whose traceried window was now softly touched by the moonlight All was still and silent, except the rush of the rapid river, as I sat down upon a stone bench to enjoy the scene and luxuriate in its tranquil serenity. I had not believed Ireland contained such a spot, for there was all the trim neatness and careful propriety of an English village, with that luxuriance of verdure and wild beauty so eminently Irish. How was it that I had never heard of it before? Were others aware of it, or was the discovery strictly my own? Or can it possibly be that all this picturesque loveliness is but the effect of a mellow moon? While I thus questioned myself, I heard the sound of a quick footstep rapidly approaching, and soon afterwards the pleasant tone of a rich voice humming an opera air. I arose, and saw a tall, athletic-looking figure, with rod and fishing-basket, approaching me.

“May I ask you, sir,” said I, addressing him, “if this village contains an inn?”

“There is, or rather there was, a sort of inn here,” said he, removing his cigar as he spoke; “but the place is so little visited that I fancy the landlord found it would not answer, and so it is closed at this moment.”

“But do visitors—tourists—never pass this way?”

“Yes, and a few salmon-fishers, like myself, come occasionally in the season; but then we dispose ourselves in little lodgings, here and there, some of us with the farmers, one or two of us with the priest.”

“Father Dyke?” broke I in.

“Yes; you know him, perhaps?”

“I have heard of him, and met him, indeed,” added I, after a pause. “Where may his house be?”

“The prettiest spot in the whole glen. If you ‘d like to see it in this picturesque moonlight, come along with me.”

I accepted the invitation at once, and we walked on together. The easy, half-careless tone of the stranger, the loose, lounging stride of his walk, and a certain something in his mellow voice, seemed to indicate one of those natures which, so to say, take the world well,—temperaments that reveal themselves almost immediately. He talked away about fishing as he went, and appeared to take a deep interest in the sport, not heeding much the ignorance I betrayed on the subject, nor my ignoble confession that I had never adventured upon anything higher than a worm and a quill.

“I’m sure,” said he, laughingly, “Tom Dyke never encouraged you in such sporting-tackle, glorious fly-fisher as he is.”

“You forget, perhaps,” replied I, “that I scarcely have any acquaintance with him. We met once only at a dinnerparty.”

“He’s a pleasant fellow,” resumed he; “devilish wideawake, one must say; up to most things in this same world of ours.”

“That much my own brief experience of him can confirm,” said I, dryly, for the remark rather jarred upon my feelings.

“Yes,” said he, as though following out his own train of thought “Old Tom is not a bird to be snared with coarse lines. The man must be an early riser that catches him napping.”

I cannot describe how this irritated me. It sounded like so much direct sarcasm upon my weakness and want of acuteness.

“There’s the ‘Rosary;’ that’s his cottage,” said he, taking my arm, while he pointed upward to a little jutting promontory of rock over the river, surmounted by a little thatched cottage almost embowered in roses and honeysuckles. So completely did it occupy the narrow limits of ground, that the windows projected actually over the stream, and the creeping plants that twined through the little balconies hung in tangled masses over the water. “Search where you will through the Scottish and Cumberland scenery, I defy you to match that,” said my companion; “not to say that you can hook a four-pound fish from that little balcony on any summer evening while you smoke your cigar.”

“It is a lovely spot, indeed,” said I, inhaling with ecstasy the delicious perfume which in the calm night air seemed to linger in the atmosphere.

“He tells me,” continued my companion,—“and I take his word for it, for I am no florist,—that there are seventy varieties of the rose on and around that cottage. I can answer for it that you can’t open a window without a great mass of flowers coming in showers over you. I told him, frankly, that if I were his tenant for longer than the fishing-season, I 'd clear half of them away.”

“You live there, then?” asked I, timidly.

“Yes, I rent the cottage, all but two rooms, which he wished to keep for himself, but which he now writes me word may be let, for this month and the next, if a tenant offer. Would you like them?” asked he, abruptly.

“Of all things—that is—I think so—I should like to see them first!” muttered I, half startled by the suddenness of the question.

“Nothing easier,” said he, opening a little wicket as he spoke, and beginning to ascend a flight of narrow steps cut in the solid rock. “This is a path of my designing,” continued he; “the regular approach is on the other side; but this saves fully half a mile of road, though it be a little steep.”