Project Gutenberg's Davenport Dunn, Volume 2 (of 2), by Charles James Lever

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Davenport Dunn, Volume 2 (of 2)

A Man Of Our Day

Author: Charles James Lever

Illustrator: Phiz.

Release Date: May 11, 2010 [EBook #32342]

Last Updated: September 3, 2016

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DAVENPORT DUNN, VOLUME 2 (OF 2) ***

Produced by David Widger

CONTENTS

DAVENPORT DUNN: A MAN OF OUR DAY

CHAPTER I. THE TELEGRAPHIC DESPATCH

CHAPTER II. "THE RUN FOR GOLD”

CHAPTER III. A NOTE FROM DAVIS

CHAPTER IV. LAZARUS, STEIN, GELDWECHSLER

CHAPTER V. A VILLAGE NEAR THE RHINE

CHAPTER VI. IMMINENT TIDINGS

CHAPTER VII. A DISCURSIVE CONVERSATION

CHAPTER VIII. A FAMILY MEETING

CHAPTER IX. A SAUNTER BY MOONLIGHT

CHAPTER X. A RIDE TO NEUWIED

CHAPTER XI. HOW GROG DAVIS DISCOURSED, AND ANNESLEY BEECHER LISTENED

CHAPTER XII. REFLECTIONS OF ANNESLEY BEECHER

CHAPTER XIII. A DARK CONFIDENCE

CHAPTER XIV. SOME DAYS AT GLENGARIFF

CHAPTER XV. A BRIDLE-PATH

CHAPTER XVI. THE DISCOVERY

CHAPTER XVII. THE DOUBLE BLUNDER

CHAPTER XVIII. DOWNING STREET

CHAPTER XIX. THE COTTAGE NEAR SNOWDON

CHAPTER XX. A SUPPER

CHAPTER XXI. A SHOCK

CHAPTER XXII. A MASTER AND MAN

CHAPTER XXIII. ANNESLEY BEECHER IN A NEW PART

CHAPTER XXIV. A DEAD HEAT

CHAPTER XXV. STUNNING TIDINGS

CHAPTER XXVI. UNPLEASANT EXPLANATIONS

CHAPTER XXVII. OVERREACHINGS

CHAPTER XXVIII. AT ROME

CHAPTER XXIX. THE TWO VISCOUNTESSES

CHAPTER XXX. MRS. SEACOLE’S

CHAPTER XXXI. THE CONVENT OF ST. GEORGE

CHAPTER XXXII. SHOWING “HOW WOUNDS ARE HEALED”

CHAPTER XXXIII. "GROG” IN COUNCIL

CHAPTER XXXIV. THE TRAIN

CHAPTER XXXV. THE TRIAL

CHAPTER XXXVI. THE END OF ALL THINGS

When Mr. Davenport Dunn entered the drawing-room before dinner on that day, his heart beat very quickly as he saw Lady Augusta Arden was there alone. In what spirit she remembered the scene of the morning,—whether she felt resentment towards him for his presumption, was disposed to scoff down his pretensions, or to regard them, if not with favor, with at least forgiveness, were the themes on which his mind was yet dwelling. The affable smile with which she now met him did more to resolve these doubts than all his casuistry.

“Was it not very thoughtful of me,” said she, “to release you this morning, and suffer you to address yourself to the important things which claimed your attention? I really am quite vain of my self-denial.”

“And yet, Lady Augusta,” said he, in a low tone, “I had felt more flattered if you had been less mindful of the exigency, and been more interested in what I then was speaking of.”

“What a selfish speech!” said she, laughing. “Now that my forbearance has given you all the benefits it could confer, you turn round and say you are not grateful for it. I suppose,” added she, half pettishly, “the despatch was not very pressing after all, and that this was the cause of some disappointment.”

“I am unable to say,” replied he, calmly.

“What do you mean? Surely, when you read it—”

“But I have not read it,—there it is still, just as you saw-it,” said he, producing the packet with the seal unbroken.

“But really, Mr. Dunn,” said she, and her face flushed up as she spoke, “this does not impress me with the wonderful aptitude for affairs men ascribe to you. Is it usual to treat these messages so cavalierly?”

“It never happened with me till this morning, Lady Augusta,” said he, in the same low tone. “Carried away by an impulse which I will not try to account for, I had dared to speak to you of myself and of my future in a way that showed how eventful to both might prove the manner in which you heard me.”

“Well, Dunn,” cried Lord Glengariff, entering, “I suppose you have made a day of work of it; we have never seen you since breakfast.”

“On the contrary, my Lord,” replied he, in deep confusion, “I have taken my idleness in the widest sense. Never wrote a line,—not looked into a newspaper.”

“Wouldn’t even open a telegraphic message which came to his hands this morning,” said Lady Augusta, with a malicious drollery in her glance towards him.

“Incredible!” cried my Lord.

“Quite true, I assure your Lordship,” said Dunn, in deeper confusion, and not knowing what turn to give his explanation.

“The fact is,” broke in Lady Augusta, hurriedly, “Mr. Dunn was so implicit in his obedience to our prescription of perfect rest and repose, that he made it a point of honor not even to read a telegram without permission.”

“I must say it is very flattering to us,” said Lord Glengariff; “but now let us reward the loyalty, and let him see what his news is.”

Dunn looked at Lady Augusta, who, with the very slightest motion of her head, gave consent, and he broke open the despatch.

Dunn crushed the paper angrily in his hand when he finished reading it, and muttered some low words of angry meaning.

“Nothing disagreeable, I trust?” asked his Lordship.

“Yes, my Lord, something even worse than disagreeable,” said he; then flattening out the crumpled paper, he held it to him to read.

Lord Glengariff, putting on his spectacles, perused the document slowly, and then, turning towards Dunn, in a voice of deep agitation, said, “This is very disastrous indeed; are you prepared for it?”

Without attending to the question, Dunn took the despatch from Lord Glengariff, and handed it to Lady Augusta.

“A run for gold!” cried she, suddenly. “An attempt to break the Ossory Bank! What does it all mean? Who are they that make this attack?”

“Opponents—some of them political, some commercial, a few, perhaps, men personally unfriendly,—enemies of what they call my success!” and he sighed heavily on the last word. “Let me see,” said he, slowly, after a pause; “to-day is Thursday—to-morrow will be the 28th—heavy payments are required for the Guatemala Trunk Line,—something more than forty thousand pounds to be made up. The Parma Loan, second instalment, comes on the 80th.”

“Dinner, my Lord,” said a servant, throwing open the door.

“A thousand pardons, Lady Augusta,” said Dunn, offering his arm. “I am really shocked at obtruding these annoyances upon your notice. You see, my Lord,” added he, gayly, “one of the penalties of admitting the ‘working-men of life’ into your society.”

It was only as they passed on towards the dinner-room that Lord Glengariff noticed Miss Kellett’s absence.

“She has a headache or a cold, I believe,” said Lady Augusta, carelessly; and they sat down to dinner.

So long as the servants were present the conversation ranged over commonplace events and topics, little indeed passing, since each seemed too deeply impressed with grave forebodings for much inclination for mere talking. Once alone—and Lord Glengariff took the earliest moment to be so—they immediately resumed the subject of the ill-omened despatch.

“You are, at all events, prepared, Dunn?” said the Earl; “this onslaught does not take you by surprise?”

“I am ashamed to say it does, my Lord,” said he, with a painful smile. “I was never less suspectful of any malicious design upon me. I was, for the first time perhaps in all my life, beginning to feel strong in the consciousness that I had faithfully performed my allotted part in the world, advanced the great interests of my country and of humanity generally. This blow has, therefore, shocked me deeply.”

“What a base ingratitude!” exclaimed Lady Augusta, indignantly.

“After all,” said Dunn, generously, “let us remember that I am not a fair judge in my own cause. Others have taken, it may be, another reading of my character; they may deem me narrow-minded, selfish, and ambitious. My very success—I am not going to deny it has been great—may have provoked its share of enmity. Why, the very vastness and extent of my projects were a sort of standing reproach to petty speculators and small scheme-mongers.”

“So that it has really come upon you unawares?” said the Earl, reverting to his former remark.

“Completely so, my Lord. The tranquil ease and happiness I have enjoyed under this roof—the first real holiday in a long life of toil—are the best evidences I can offer how little I could have anticipated such a stroke.”

“Still I fervently hope it will not prove more than inconvenience,” said he, feelingly.

“Not even so much, my Lord, as regards money. I cannot believe that the movement will be general. There is no panic in the country, rents are paid, prices remunerating, markets better than we have seen them for years; the sound sense and intelligence of the people will soon detect in this attack the prompting of some personal malice. In all likelihood a few thousands will meet the whole demand.”

“I am so glad to hear you say so!” said Lady Augusta, smiling. “Really, when I think of all our persuasions to detain you here, I never could acquit us of some sort of share in any disaster your delay might have occasioned.”

“Oh, Dunn would never connect his visit here with such consequences, I ‘m certain,” said the Earl.

“Assuredly not, my Lord,” said he; and as his eyes met those of Lady Augusta, he grew red, and felt confused.

“Are your people—your agents and men of business, I mean,” said the Earl—“equal to such an emergency as the present, or will they have to look to you for guidance and direction?”

“Merely to meet the demand for gold is a simple matter, my Lord,” said Dunn, “and does not require any effort of mind or forethought. To prevent the back-water of this rushing flood submerging and engulfing other banking-houses; to defend, in a word, the lines of our rivals and enemies; to save from the consequences of their recklessness the very men who have assailed us,—these are weighty cares!”

“And are you bound in honor to take this trouble in their behalf?”

“No, my Lord, not in honor any more than in law, but bound by the debt we owe to that commercial community by whose confidence we have acquired fortune. My position at the head of the great industrial movement in this country imposes upon me the great responsibility that ‘no injury should befall the republic’ Against the insane attacks of party hate, factious violence, or commercial knavery, I am expected to do my duty, nay, more, I am expected to be provided with means to meet whatever emergency may arise,—defeat this scheme, expose that, denounce the other. Am I wrong in calling these weighty cares?”

Self-glorification was not usually one of Davenport Dunn’s weaknesses,—indeed, “self,” in any respect, was not a theme on which he was disposed to dwell,—and yet now, for reasons which may better be suspected than alleged, he talked in a spirit of even vain exultation of his plans, his station, and his influence. If it was something to display before the peer claims to national respect, which, if not so ancient, were scarcely less imposing than his own, it was more pleasing still to dilate upon a theme to which the peer’s daughter listened so eagerly. It was, besides, a grand occasion to exhibit the vast range of resources, the widespread influences, and far-reaching sympathies of the great commercial man, to show him, not the mere architect of his own fortune, but the founder of a nation’s prosperity. While he thus held forth, and in a strain to which fervor had lent a sort of eloquence, a servant entered with another despatch.

“Oh! I trust this brings you better news,” cried Lady Augusta, eagerly; and, as he broke the envelope, he thanked her with a grateful look.

“Well?” interposed she, anxiously, as he gazed at the lines without speaking,—“well?”

“Just as I said,” muttered Dunn, in a deep and suppressed voice,—“a systematic plot, a deep-laid scheme against me.”

“Is it still about the Bank?” asked the Earl, whose interest had been excited by the tenor of the recent conversation.

“Yes, my Lord; they insist on making me out a bubble speculator, an adventurer, a Heaven knows what of duplicity and intrigue. I would simply ask them: ‘Is the wealth with which this same Davenport Dunn has enriched you real, solid, and tangible; are the guineas mint-stamped; are the shares true representatives of value?’ But why do I talk of these people? If they render me no gratitude, they owe me none,—my aims were higher and greater than ever they or their interests comprehended.” From the haughty defiance of his tone, his voice fell suddenly to a low and quick key, as he said: “This message informs me that the demand upon the Ossory to-morrow will be a great concerted movement. Barnard, the man I myself returned last election for the borough, is to head it; he has canvassed the county for holders of our notes, and such is the panic that the magistrates have sent for an increased force of police and two additional companies of infantry. My man of business asks, ‘What is to be done?’”

“And what is to be done?” asked the Earl.

“Meet it, my Lord. Meet the demand as our duty requires us.”

There was a calm dignity in the manner Dunn spoke the words that had its full effect upon the Earl and his daughter. They saw this “man of the people” display, in a moment of immense peril, an amount of cool courage that no dissimulation could have assumed. As they could, and did indeed say afterwards, when relating the incident, “We were sitting at the dessert, chatting away freely about one thing or another, when the confirmed tidings arrived by telegraph that an organized attack was to be made against his credit by a run for gold. You should really have seen him,” said Lady Augusta, “to form any idea of the splendid composure he manifested. The only thing like emotion he exhibited was a sort of haughty disdain, a proud pity, for men who should have thus requited the great services he had been rendering to the country.”

It is but just to own that he did perform his part well; he acted it, too, as theatrical critics would say, “chastely;” that is, there was no rant, no exaggeration,—not a trait too much, not a tint too strong.

“I wish I knew of any way to be of service to you in this emergency, Dunn,” said the Earl, as they returned to the drawing-room; “I’m no capitalist, nor have I a round sum at my command—”

“My dear Lord,” broke in Dunn, with much feeling, “of money I can command whatever amount I want. Baring, Hope, Rothschild, any of them would assist me with millions, if I needed them, to-morrow, which happily, however, I do not. There is still a want which they cannot supply, but which, I am proud to say, I have no longer to fear. The kind sympathy of your Lordship and Lady Augusta has laid me under an obligation—” Here Mr. Dunn’s voice faltered; the Earl grasped his hand with a generous clasp, and Lady Augusta carried her handkerchief to her eyes as she averted her head.

“What a pack of hypocrites!” cries our reader, in disgust. No, not so. There was a dash of reality through all this deceit. They were moved,—their own emotions, the tones of their own voices, the workings of their own natures, had stirred some amount of honest sentiment in their hearts; how far it was alloyed by less worthy feeling, to what extent fraud and trickery mingled there, we are not going to tell you,—perhaps we could not, if we would.

“You mean to go over to Kilkenny, then, to-morrow, Dunn?” asked his Lordship, after a painful pause.

“Yes, my Lord, my presence is indispensable.”

“Will you allow Lady Augusta and myself to accompany you? I believe and trust that men like myself have not altogether lost the influence they once used to wield in this country, and I am vain enough to imagine I may be useful.”

“Oh, my Lord, this overwhelms me!” said Dunn, and covered his eyes with his hand.

The great Ossory Bank, with its million sterling of paid-up capital, its royal charter, its titled directory, and its shares at a premium, stood at the top of Patrick Street, Kilkenny, and looked, in the splendor of its plate-glass windows and the security of its iron railings, the very type of solvency and safety. The country squire ascended the hall-door steps with a sort of feeling of acquaintanceship, for he had known the Viscount who once lived there in days before the Union, and the farmer experienced a sense of trustfulness in depositing his hard-earned gains in what he regarded as a temple of Croesus. What an air of prosperity and business did the interior present! The massive doors swung noiselessly at the slightest touch, meet emblem of the secrecy that prevailed, and the facility that pervaded all transactions, within. What alacrity, too, in that numerous band of clerks who counted and cashed and checked unceasingly! How calmly they passed from desk to desk, a word, a mere whisper, serving for converse; and then what a grand and mysterious solemnity about that back office with its double doors, within which some venerable cashier, bald-headed and pursy, stole at intervals to consult the oracle who dwelt within! In the spacious apartment devoted to cash operations, nothing denoted the former destiny of the mansion but a large fireplace, with a pretentious chimney-piece of black oak, over which a bust of our gracious Queen now figured, an object of wonderment and veneration to many a frieze-coated gazer.

On the morning of the 12th August, to which day we have brought our present history, the street in front of the Bank presented a scene of no ordinary interest. From an early hour people continued to pour in, till the entire way was choked up with carriages and conveyances of every description, from the well-equipped barouche of the country gentleman to the humblest “shandradan” of the petty farmer. Sporting-looking fellows upon high-conditioned thoroughbreds, ruddy old squires upon cobs, and hard-featured country-folk upon shaggy ponies, were all jammed up together amidst a dense crowd of foot passengers. A strong police-force was drawn up in front of the Bank, although nothing in the appearance of the assembled mass seemed to denote the necessity for their presence. A low murmur of voices ran through the crowd as each talked to his neighbor, consulting, guessing, and speculating, as temperament inclined: some were showing placards and printed notices they had received through the post; some pointed to newspaper paragraphs; others displayed great rolls of notes; but all talked with a certain air of sadness that appeared to presage coming misfortune. As ten o’clock drew nigh, the hour for opening the Bank, the excitement rose to a painful pitch; every eye was directed to the massive door, whose gorgeous brass knocker shone with a sort of insolent brilliancy in the sun. At every moment watches were consulted, and in muttered whispers men broke their fears to those beside them. Some could descry the heads of people moving about in the cash-office, where a considerable bustle appeared to prevail; and even this much of life seemed to raise the spirits of the crowd, and the rumor ran quickly on every side that the Bank was about to open. At last the deep bell of the town-hall struck ten. At each fall of the hammer all expected to see the door move, but it never stirred; and now the pent-up feeling of the multitude might be marked in a sort of subdued growl,—a low, ill-boding sound, that seemed ta come out of the very earth. As if to answer the unspoken anger of the crowd,—a challenge accepted ere given,—a heavy crash was heard, and the police proceeded to load with ball in the face of the people,—a demonstration whose significance there was no mistaking. A cry of angry defiance burst from the assembled mass at the sight, but as suddenly was checked again as the massive door was seen to move, and then, with a loud bang, fly wide open. The rush was now tremendous. With some vague impression that everything depended upon being amongst the first, the people poured in with all the force of a mighty torrent. Each, fighting his way as if for life itself, regardless of the cries of suffering about him, strove to get forward; nor could all the efforts of the police avail to restrain them in the slightest. Bleeding, wounded, half suffocated, with bruised faces and clothes torn to tatters, they struggled on,—no deference to age, no respect to condition. It was a fearful anarchy, where every thought of the past was lost in the present emergency. On they poured, breathless and bloody, with gleaming eyes and faces of demoniacal meaning; they pushed, they jostled, and they tore, till the first line gained the counter, against which the force behind now threatened to crush them to death.

What a marvellous contrast to the storm-tossed multitude, steaming and disfigured, was the calm attitude of the clerks within the counter! Not deigning, as it seemed, to bestow a glance upon the agitated scene before them, they moved placidly about, pen behind the ear, in voices of ordinary tone, asking what each wanted, and counting over the proffered notes with all the impassiveness of every-day habit. “Gold for these, did you say?” they repeated, as though any other demand met the ear! Why, the very air rang with the sound, and the walls gave back the cry. From the wild voice of half-maddened recklessness to the murmur that broke from fainting exhaustion, there was but one word,—“Gold!” A drowning crew, as the surging waves swept over them, never screamed for succor with wilder eagerness than did that tangled mass shout, “Gold, gold!”

In their savage energy they could scarcely credit that their demands should be so easily complied with; they were half stupefied at the calm indifference that met their passionate appeal. They counted and recounted the glittering pieces over and over, as though some trick were to be apprehended, some deception to be detected. When drawn or pulled back from the counter by others eager as themselves, they might be seen in corners, counting over their money, and reckoning it once more. It was so hard to believe that all their terrors were for nothing, their worst fears without a pretext. Even yet they couldn’t imagine but that the supply must soon run short, and they kept asking those that came away whether they, too, had got their gold. Hour after hour rolled on, and still the same demand, and still the same unbroken flow of the yellow tide continued. Some very large checks had been presented; but no sooner was their authenticity acknowledged than they were paid. An agent from another bank arrived with a formidable roll of “Ossory” notes, but was soon seen issuing forthwith two bursting little bags of sovereigns. Notwithstanding all this, the pressure never ceased for a moment; nay, as the day wore on, the crowds seemed to have grown denser and more importunate; and when the half-exhausted clerks claimed a few minutes’ respite for a biscuit and a glass of wine, a cry of impatience burst from the insatiable multitude. It was three o’clock. In another hour the Bank would close, as many surmised, never to open again. It was evident, from the still increasing crowd and the excitement that prevailed, how little confidence the ready payments of the Bank had diffused. They who came forth loaded with gold were regarded as fortunate, while they who still waited for their turn were in all the feverish torture of uncertainty.

A little after three the crowd was cleft open by the passage of a large travelling-barouche, which, with four steaming posters, advanced slowly through the dense mass.

“Who comes here with an earl’s coronet?” said a gentleman to his neighbor, as the carriage passed. “Lord Glengariff, and Davenport Dunn himself, by George!” cried he suddenly.

The words were as quickly caught up by those at either side, and the news, “Davenport Dunn has arrived,” ran through the immense multitude. If there was an eager, almost intense anxiety to catch a glimpse of him, there was still nothing that could indicate, in the slightest degree, the state of popular feeling towards him. Slightly favorable it might possibly have been, inasmuch as a faint effort at a cheer burst forth at the announcement of his name; but it was repressed just as suddenly, and it was in a silence almost awful that he descended from the carriage at the private door of the Bank.

“Do, I beg of you, Mr. Dunn,” said Lady Augusta, as he stood to assist her to alight; “let me entreat of you not to think of us. We can be most comfortably accommodated at the hotel.”

“By all means, Dunn. I insist upon it,” broke in the Earl.

“In declining my poor hospitality, my Lord,” said Dunn, “you will grieve me much, while you will also favor the impression that I am not in a condition to offer it.”

“Ah! quite true,—very justly observed. Dunn is perfectly right, Augusta. We ought to stop here.” And he descended at once, and gave his hand to his daughter.

Lady Augusta turned about ere she entered the house, and looked at the immense crowd before her. There was something of almost resentfulness in the haughty gaze she bestowed; but, let us own, the look, whatever it implied, well became her proud features; and more than one was heard to say, “What a handsome woman she is!”

This little incident in the day’s proceedings gave rise to much conjecture, some auguring that events must be grave and menacing when Dunn’s own presence was required, others inferring that he came to give assurance and confidence to the Bank. Nor was the appearance of Lord Glen-gariff less open to its share of surmise; and many were the inquiries how far he was personally interested,—whether he was a large stockholder of the concern, or deep in its books as debtor. Leaving the speculative minds who discussed the subject without doors, let us follow Mr. Dunn, as, with Lady Augusta on his arm, he led the way to the drawing-room.

The rooms were handsomely furnished, that to the back opening upon a conservatory filled with rich geraniums, and ornamented with a pretty marble fountain, now in full play. Indeed, so well had Dunn’s orders been attended to, that the apartments which he scarcely occupied for above a day or so in a twelvemonth had actually assumed the appearance of being in constant use. Books, prints, and newspapers were scattered about, fresh flowers stood in the vases, and recent periodicals lay on the tables.

“What a charming house!” exclaimed Lady Augusta; and, really, the approbation was sincere, for the soft-cushioned sofas, the perfumed air, the very quiet itself, were in delightful contrast to the heat and discomfort of a journey by “rail.”

It was in vain Dunn entreated his noble guests to accept some luncheon; they peremptorily refused, and, in fact, declared that they would only remain there on the condition that he bestowed no further thought upon them, addressing himself entirely to the weighty cares around him.

“Will you, at least, tell me at what hour you’d like dinner, my Lord? Shall we say six?”

“With all my heart. Only, once more, I beg, never think of us. We are most comfortable here, and want for nothing.”

With a deep bow of obedience, Dunn moved towards the door, when suddenly Lady Augusta whispered a few rapid words in her father’s ear.

“Stop a moment, Dunn!” cried the Earl. “Augusta is quite right. The observation is genuine woman’s wit She says I ought to go down along with you, to show myself in the Bank; that my presence there will have a salutary effect. Eh, what d’ye think?”

“I am deeply indebted to Lady Augusta for the suggestion,” said Dunn, coloring highly. “There cannot be a doubt that your Lordship’s countenance and support at such a moment are priceless.”

“I ‘m glad you think so, glad she thought of it,” muttered the Earl, as he arranged his white locks before the glass, and made a sort of hasty toilet for his approaching appearance in public.

To judge from the sensation produced by the noble Lord’s appearance in the Bank, Lady Augusta’s suggestion was admirable. The arrival of a wagon-load of bullion could scarcely have caused a more favorable impression. If Noah had been an Englishman, the dove would have brought him not an olive-branch but a lord. I say it in no spirit of sarcasm or sneer, for, coteris paribus, lords are better company than commoners; I merely record it passingly, as a strong trait of our people and our race. So was it now, that from the landed gentleman to the humblest tenant-farmer, the Earl’s presence seemed a fresh guarantee of solvency. Many remarked that Dunn looked pale,—some thought anxious; but all agreed that the hearty-faced, white-haired old nobleman at his side was a perfect picture of easy self-satisfaction.

They took their seats in the cash-office, within the counter, to be seen by all, and see everything that went forward. If Davenport Dunn regarded the scene with a calm and unmoved indifference, his attention being, in fact, more engrossed by his newspaper than by what went on around, Lord Glengariff’s quick eye and ear were engaged incessantly. He scanned the appearance of each new applicant as he came up to the table; he listened to his demand, noted its amount, and watched with piercing glance what effect it might produce on the cashier. Nor was he an unmoved spectator of the scene; for while he simply contented himself with an angry stare at the frieze-coated peasant, he actually scowled an insolent defiance when any of higher rank or more pretentious exterior presented himself, muttering in broken accents beneath his breath, “Too bad, too bad!” “Gross ingratitude!” “A perfect disgrace!” and so on.

He was at the very climax of his indignation, when a voice from the crowd addressed him with “How d’ ye do, my Lord? I was not aware you were in this part of the country.”

He put up his double eyeglass, and speedily recognized the Mr. Barnard whom Dunn mentioned as so unworthily requiting all he had done for him.

“No, sir,” said the Earl, haughtily; “and just as little did I expect to see you here on such an errand as this. In my day, country gentlemen were the first to give the example of trust and confidence, and not foremost in propagating unworthy apprehensions.”

“I’m not a partner in the Bank, my Lord, and know nothing of its solvency,” said the other, as he handed in two checks over the counter.

“Eight thousand six hundred and forty-eight. Three thousand, twelve, nine, six,” said the clerk, mechanically. “How will you have it, sir?”

“Bank of Ireland notes will do.”

Dunn lifted his eyes from the paper, and then, raising his hat, saluted Mr. Barnard.

“I trust you left Mrs. Barnard well?” said he, in a calm voice.

“Yes, thank you—well—quite well,” said Barnard, in some confusion.

“Will you remember to tell her that she shall have the acorns of the Italian pines next week? I have heard of their arrival at the Custom-house.”

While Barnard muttered a very confused expression of thanks, the old Earl looked from one to the other of the speakers in a sort of bewilderment. Where was the angry indignation he had looked for from Dunn,—where the haughty denunciation of a black ingratitude?

“Why, Dunn, I say,” whispered he, “isn’t this Barnard the fellow you spoke of,—the man you returned to Parliament t’ other day?”

“The same, my Lord,” replied Dunn, in a low, cautious voice. “He is here exacting a right,—a just right,—and no more. It is not now, nor in this place, that I would remind him how ungraciously he has treated me. This day is his. Mine will come yet.”

Before Lord Glengariff could well recover from the astonishment of this cold and calculating patience, Mr. Hankes pushed his way through the crowd, with an open letter in his hand.

It was a telegram just received, with an account of an attack made by the mob on Mr. Dunn’s house in Dublin. Like all such communications, the tidings were vague and unsatisfactory: “A terrific attack by mob on No. 18. Windows smashed, and front door broken, but not forced. Police repulsed; military sent for.”

“So much for popular gratitude, my Lord,” said Dunn, as he handed the slip of paper to the Earl. “Fortunately, it was never the prize on which I had set my heart. Mr. Hankes,” said he, in a bland, calm voice, “the crowd seems scarcely diminished outside. Will you kindly affix a notice on the door, to state that, to convenience the public, the Bank will on this day continue open till five o’clock?”

“By Heaven! they don’t deserve such courtesy!” cried the old Lord, passionately. “Be as just as you please, but show them no generosity. If it be thus they treat the men who devote their best energies, their very lives, to the country, I, for one, say it is not a land to live in, and I spurn them as countrymen!”

“What would you have, my Lord? The best troops have turned and fled under the influence of a panic; the magic words, ‘We are mined!’ once routed the very column that had stormed a breach! You don’t expect to find the undisciplined masses of mankind more calmly courageous than the veterans of a hundred fights.”

A wild hoarse cheer burst forth in the street at this moment, and drowned all other sounds.

“What is it now? Are they going to attack us here?” cried the Earl.

The cry again arose, louder and wilder, and the shouts of “Dunn forever! Dunn forever!” burst from a thousand voices.

“The placard has given great satisfaction, sir,” said Hankes, reappearing. “Confidence is fully restored.”

And, truly, it was strange to see how quickly a popular sentiment spread its influence; for they who now came forward to exchange their notes for gold no longer wore the sturdy air of defiance of the earlier applicants, but approached half reluctantly, and with an evident sense of shame, as though yielding to an ignoble impulse of cowardice and fear. The old Earl’s haughty stare and insolent gaze were little calculated to rally the diffident; for with his double eyeglass he scanned each new-comer with the air of a man saying, “I mark, and I ‘ll not forget you!”

What a contrast was Dunn’s expression,—that look so full of gentle pity and forgiveness! Nothing of anger, no resentfulness, disfigured the calm serenity of his pale features. He had a word of recognition—even a smile and a kind inquiry—for some of those who now bashfully tried to screen themselves from notice. The great rush was already over; a visible change had come over that vast multitude who so lately clamored aloud for gold. The very aspect of that calm, unmoved face was a terrible rebuke to their unworthy terror.

“It’s nigh over, sir,” whispered Hankes to his chief, as he stood with his massive gold watch in the hollow of his hand. “Seven hundred only have been paid out in the last twelve minutes. The battle is finished!”

The vociferous cheering without continued unceasingly, and yells for Dunn to come forth and show himself filled the air.

“Do you hear them?” asked Lord Glengariff, looking eagerly at Dunn.

“Yes, my Lord. It is a very quick reaction. Popular opinion is generally correct in the main; but it is rare to find it reversing its own judgments so suddenly.”

“Very dispassionately spoken, sir,” said the old Lord, haughtily; “but what if you had been unprepared for this onslaught to-day,—what if they had succeeded in compelling you to suspend payments?”

“Had such been possible, my Lord, we would have richly deserved any reverse that might have befallen us. What is it, Hankes?” cried he, as that gentleman endeavored to get near him.

“You’ll have to show yourself, sir; you must positively address them in a few words from the balcony.”

“I do not think so, Hankes. This is a mere momentary burst of popular feeling.”

“Not at all, sir. Listen to them now; they are shouting madly for you. To decline the call will be taken as pride. I implore you to come out, if only for a few minutes.”

“I suppose he is right, Dunn,” said Lord Glengariff, half doggedly. “For my own part, I have not the slightest pretension to say how popular demonstrations—I believe that is the word for them—are to be treated. Street gatherings, in my day, were called mobs, and dispersed by horse police; our newer civilization parleys to them and flatters them. I suppose you understand the requirements of the times we live in.”

The clamor outside was now deafening, and by its tone seemed, in some sort, to justify what Hankes had said, that Dunn’s indifference to their demands would be construed into direct insult.

“Do it at once!” cried Hankes, eagerly, “or it will be too late. A few words spoken now will save us thirty thousand pounds to-morrow.”

This whisper in Dunn’s ear decided the question, and, turning to the Earl, he said, “I believe, my Lord, Mr. Hankes is right; I ought to show myself.”

“Come along, then,” said the old Lord, heartily; and he took his arm with an air that said, “I ‘ll stand by you throughout.”

Scarcely had Dunn entered the drawing-room, than Lady Augusta met him, her cheek flushed and her eyes flashing. “I am so glad,” cried she, “that you are going to address them. It is a proud moment for you.”

When the window opened, and Davenport Dunn appeared on the balcony, the wild roar of the multitude made the air tremble; for the cry was taken up by others in remote streets, and came echoing back, again and again. I have heard that consummate orators—men practised in all the arts of public speaking—have acknowledged that there is no such severe test, in the way of audience, as that mixed assemblage called a mob, wherein every class has its representative, and every gradation its type. Now, Dunn was not a great public speaker. The few sentences he was obliged to utter on the occasions of his health being drunk cost him no uncommon uneasiness; he spoke them, usually, with faltering accents and much diffidence. It happens, however, that the world is often not displeased at these small signs of confusion—these little defects in oratorical readiness—in men of acknowledged ability, and even prefer them to the rapid flow and voluble ease of more practised orators. There is, so to say, a mock air of sincerity in the professions of a man whose feelings seem fuller than his words,—something that implies the heart to be in the right place, though the tongue be but a poor exponent of its sentiments; and lastly, the world is always ready to accept the embarrassment of the speaker as an evidence of the grateful emotions that are swaying him. Hence the success of country gentlemen in the House; hence the hearty cheers that follow the rambling discursiveness of bucolic eloquence!

If Mr. Dunn was not an orator, he was a keen and shrewd observer, and one fact he had noticed, which was that the shouts and cries of popular assemblages are to an indifferent speaker pretty much what an accompaniment is to a bad singer,—the aids by which he surmounts difficult passages and conceals his false notes. Mr. Hankes, too, well understood how to lead this orchestra, and had already taken his place on the steps of the door beneath.

Dunn stood in front of the balcony, Lord Glengariff at his side and a little behind him. With one hand pressed upon his heart, he bowed deeply to the multitude. “My kind friends,” said he, in a low voice, but which was audible to a great distance, “it has been my fortune to have received at different times of my life gratifying assurances of sympathy and respect, but never in the whole course of a very varied career do I remember an occasion so deeply gratifying to my feelings as the present. (Cheers, that lasted ten minutes and more.) It is not,” resumed he, with more energy,—“it is not at a moment like this, surrounded by brave and warm hearts, when the sentiments of affection that sway you are mingled with the emotions of my own breast, that I would take a dark or gloomy view of human nature, but truth compels me to say that the attack made this day upon my credit—for I am the Ossory Bank—(loud and wild cheering)—yes, I repeat it, for the stability of this institution I am responsible by all I possess in this world. Every share, every guinea, every acre I own are here! Far from me to impute ungenerous or unworthy motives to any quarter; but, my worthy friends, there has been foul play—(groans)—there has been treachery—(deeper groans)—and my name is not Davenport Dunn but it shall be exposed and punished. (Cries of “More power to ye,” and hearty cheers, greeted this solemn assurance.)

“I am, as you are well aware, and I glory in declaring it, one of yourselves. (Here the enthusiasm was tremendous.) By moderate abilities, hard work, and unflinching honesty—for that is the great secret—I have become that you see me to-day! (Loud cheering.) If there be amongst you any who aspire to my position, I tell him that nothing is easier than to attain it. I was a poor scholar—you know what a poor scholar is—when the generous nobleman you see now at my side first noticed me. (Three cheers for the Lord were proposed and given most heartily.) His generous patronage gave me my first impulse in life. I soon learned how to do the rest. (“That ye did;” “More power and success to ye,” here ran through the mob.) Now, it was at the table of that noble Lord—enjoying the first real holiday in thirty years of toil—that I received a telegraphic despatch, informing me there would be a run for gold upon this Bank before the week was over. I vow to you I did not believe it. I spurned the tidings as a base calumny upon the people, and as I handed the despatch to his Lordship to read, I said, ‘If this be possible—and I doubt it much—it is the treacherous intrigue of an enemy, not the spontaneous movement of the public.’ (Here Lord Glengariff bowed an acquiescence to the statement, a condescension on his part that speedily called for three vociferous cheers for “the Lord,” once more.)

“I am no lawyer,” resumed Dunn, with vigor,—“I am a plain man of the people, whose head was never made for subtleties; but this I tell you, that if it be competent for me to offer a reward for the discovery of those who have hatched this conspiracy, my first care will be on my return to Dublin to propose ten thousand pounds for such information as may establish their guilt! (Cheering for a long time followed these words.) They knew that they could not break the Bank,—in their hearts they knew that our solvency was as complete as that of the Bank of England itself,—but they thought that by a panic, and by exciting popular feeling against me, I, in my pride of heart and my conscious honesty, might be driven to some indignant reaction; that I might turn round and say, Is this the country I have slaved for? Are these the people for whose cause I have neglected personal advancement, and disregarded the flatteries of the great? Are these the rewards of days of labor and nights of anxiety and fatigue?”

They fancied, possibly, that, goaded by what I might have construed into black ingratitude, I would say, like Coriolanus, ‘I banish you!’ But they little knew either you or me, my warm-hearted friends! (Deafening cheers.) They little knew that the well-grounded confidence of a nation cannot be obliterated by the excitement of a moment. A panic in the commercial, like a thunder-storm in the physical world, only leaves the atmosphere lighter, and the air fresher than before; and so I say to you, we shall all breathe more freely when we rise to-morrow,—no longer to see the dark clouds overhead, nor hear the rumbling sounds that betoken coming storm.

“I have detained you too long. (“No, no!” vociferously broke forth.) I have spoken also too much about myself. (“Not a bit; we could listen to ye till mornin’,” shouted a wild voice, that drew down hearty laughter.) But, before I go, I wish to say, that, hard pressed as we are in the Bank—sorely inconvenienced by the demands upon us—I am yet able to ask your excellent Mayor to accept of five hundred pounds from me for the poor of this city—(what a yell followed this announcement! plainly indicating what a personal interest the tidings seemed to create )—and to add—(loud cheers)—and to add—(more cheers)—and to add,” cried he, in his deepest voice, “that the first toast I will drink this day shall be, The Boys of Kilkenny!”

It is but justice to add that Mr. Dunn’s speech was of that class of oratory that “hears” better than it reads, while his audience was also less critically disposed than may be our valued reader. At all events, it achieved a great success; and within an hour after its delivery hawkers cried through the streets of the city, “The Full and True Account of the Run for Gold, with Mr. Dunn’s Speech to the People;” and, sooth to say, that though the paper was not “cream laid,” and though many of the letters were upside down, the literature had its admirers, and was largely read. Later on, the city was illuminated, two immense letters of D. D. figuring in colored lamps in front of the town-hall, while copious libations of whiskey-punch were poured forth in honor of the Man of the People. In every rank and class, from the country gentleman who dined at the club-house, to the smallest chop-house in John Street, there was but one sentiment,—that Dunn was a fine fellow, and his enemies downright scoundrels. If a few of nicer taste and more correct feeling were not exactly pleased with his speech, they wisely kept their opinions to themselves, and let “the Ayes have it,” who pronounced it to be manly, above-board, modest, and so forth.

Throughout the entire evening Mr. Hankes was everywhere, personally or through his agents; his care was to collect public sentiment, to ascertain what popular opinion thought of the whole events of the morning, and to promote, so far as he could with safety, the flattering estimate already formed of his chief. Scarcely half an hour elapsed without Dunn’s receiving from his indefatigable lieutenant some small scrap of paper, with a few words hastily scrawled in this fashion:—

“Rice and Walsh’s, Nine o’clock.—Company in the coffee-room enthusiastic; talk of a public dinner; some propose portrait in town-hall.”

“A quarter to Ten, Judy’s, Rose Inn Street.—Comic song, with a chorus:—

“‘If for gold ye run, Says the Shan van Voght; If for gold ye run, I’ll send for Davy Dunn, He’s the boy to show ye fun, Says the Shan van Voght!’”

“Eleven o’clock, High Street.—Met the Dean, who says, ‘D. D. is an honor to us; we are all proud of him.’ The county your own when you want it.”

“Twelve o’clock.—If any one should venture to ask for gold to-morrow, he will be torn to pieces by the mob.”

Assuredly it was a triumph; and every time that the wild cheers from the crowds in the street broke in upon the converse in the drawing-room, Lady Augusta’s eyes would sparkle as she said, “I don’t wonder at your feeling proud of it all!”

And he did feel proud of it. Strange as it may seem, he was as proud as though the popularity had been earned by the noblest actions and the most generous devotion. We are not going to say why or wherefore this. And now for a season we take our leave of him to follow the fortunes of some others whose fate we seem to have forgotten. We have the less scruple for deserting Davenport Dunn at this moment, that we leave him happy, prospering, and in good company.

Am I asking too much of my esteemed reader, if I beg of him to remember where and how I last left the Honorable Annesley Beecher? for it is to that hopeful individual and his fortunes I am now about to return.

If it be wearisome to the reader to have his attention suddenly drawn from the topic before him, and his interest solicited for those he has well-nigh forgotten, let me add that it is almost as bad for the writer, who is obliged to hasten hither and thither, and, like a huntsman with a straggling pack, to urge on the tardy, correct the loiterer, and repress the eager.

When we parted with Annesley Beecher, he was in sore trouble and anxiety of mind; a conviction was on him that he was “squared,” “nobbled,” “crossed,” “potted,” or something to the like intent and with a like euphonious designation. “The Count and Spicer were conspiring to put him in a hole!” As if any “hole” could be as dark, as hopeless, and as deep as the dreary pitfall of his own helpless nature!

His only resource seemed flight; to break cover at once and run for it, appeared the solitary solution of the difficulty. There was many a spot in the map of Europe which offered a sanctuary against Grog Davis. But what if Grog were to set the law in motion, where should he seek refuge then? Some one had once mentioned to him a country with which no treaty connected us with regard to criminals. It began, if he remembered aright, with an S; was it Sardinia or Sweden or Spain or Sicily or Switzerland? It was surely one of them, but which? “What a mass of rubbish, to be sure,” thought he, “they crammed me with at Rugby, but not one solitary particle of what one could call useful learning! See now, for instance, what benefit a bit of geography might be to me!” And he rambled on in his mind, concocting an educational scheme which would really fit a man for the wear and tear of life.

It was thus reflecting he entered the inn and mounted to his room; his clothes lay scattered about, drawers were crammed with his wearables, and the table covered with a toilet equipage, costly, and not yet paid for. Who was to pack all these? Who was to make up that one portmanteau which would suffice for flight, including all the indispensable and rejecting the superfluous? There is a case recorded of a Frenchman who was diverted from his resolve on suicide by discovering that his pistols were not loaded, and, incredible as it may seem, Beecher was deterred from his journey by the thought of how he was to pack his trunk; He had never done so much for himself since he was born, and he did n’t think he could do it; at all events, he wasn’t going to try. Certain superstitious people are impressed with the notion that making a will is a sure prelude to dying; so others there are who fancy that, by the least effort on their own behalf, they are forecasting a state of poverty in which they must actually work for subsistence.

How hopelessly, then, did he turn over costly waistcoats and embroidered shirts, gaze on richly cut and crested essence-bottles and boot-boxes, whose complexity resembled mathematical instruments! In what manner they were ever conveyed so far he could not imagine. The room seemed actually filled with them. It was Rivers had “put them up;” but Rivers could no longer be trusted, for he was evidently in the “lay” against him.

He sighed heavily at this: it was a dreary, hopeless sigh over the depravity of the world and mankind in general. “And what a paradise it might be,” he thought, “if people would only let themselves be cheated quietly and peaceably, neither threatening with their solicitors, nor menacing with the police. Heaven knew how little he asked for: a safe thing now and then on the Derby, a good book on the Oaks; he wanted no more! He bore no malice nor ill-will to any man breathing; he never wished to push any fellow to the wall. If ever there was a generous heart, it beat in his bosom; and if the world only knew the provocation he had received! No matter, he would never retaliate,—he ‘d die game, be a brick to the last;” and twenty other fine things of the same sort that actually brought the tears to his own eyes over his own goodness.

Goodness, however, will not pack a trunk, nor will moral qualities, however transcendent, fold cravats and dress-coats, and he looked very despondently around him, and thought over what he half fancied was the only thing he could n’t do. So accustomed had he been of late to seek Lizzy Davis’s counsel in every moment of difficulty, that actually, without knowing it, he descended now to the drawing-room, some vague, undefined feeling impelling him to be near her.

She was singing at the piano, all alone, as he entered; the room, as usual, brilliantly lighted up as if to receive company, rare flowers and rich plants grouped tastefully about, and “Daisy”—for she looked that name on this occasion—in one of those charming “toilettes” whose consummate skill it is to make the most costly articles harmonize into something that seems simplicity itself. She wore a fuchsia in her hair, and another—only this last was of coral and gold elaborately and beautifully designed—on the front of her dress, and, except these, nothing more of ornament.

“Tutore mio,” said she, gayly, as he entered, “you have treated me shamefully; for, first of all, you were engaged to drive with me to the Kreutz Berg, and, secondly, to take me to the opera, and now, at half-past nine, you make your appearance. How is this, Monsieur? Expliquez-vous.”

“Shall I tell the truth?” said he.

“By all means, if anything so strange should n’t embarrass you.”

“Well, then, I forgot all about both the drive and the opera. It’s all very well to laugh,” said he, in a tone of half pique; “young ladies, with no weightier cares on their hearts than whether they ought to wear lilac or green, have very little notion of a man’s anxieties. They fancy that life is a thing of white and red roses, soft music and bouquets; but it ain’t.”

“Indeed! are you quite sure?” asked she, with an air of extreme innocence.

“I suspect I am,” said he, confidently; “and there’s not many a man about town knows more of it than I do.”

“And now, what may be the cares, or, rather, for I don’t want to be curious, what sort of cares are they that oppress that dear brain? Have you got any wonderful scheme for the amelioration of mankind to which you see obstacles? Are your views in politics obstructed by ignorance or prejudice? Have you grand notions about art for which the age is not ripe; or are you actually the author of a wonderful poem that nobody has had taste enough to appreciate?”

“And these are your ideas of mighty anxieties, Miss Lizzy?” said he, in a tone of compassionate pity. “By Jove! how I’d like to have nothing heavier on my heart than the whole load of them.”

“I think you have already told me you never were crossed in love?”

“Well, nothing serious, you know. A scratch or so, as one may say, getting through the bushes, but never a cropper,—nothing like a regular smash.”

“It would seem to me, then, that you have enjoyed a singularly fortunate existence, and been just as lucky in life as myself.”

Beecher started at the words. What a strange chaos did they create within him! There is no tracing the thoughts that came and went, and lost themselves in that poor bewildered head. The nearest to anything like, consistency was the astonishment he felt that she—Grog Davis’s daughter—should ever imagine she had drawn a prize in the world’s lottery.

“Yes, Mr. Beecher,” said she, with the ready tact with which she often read his thoughts and answered them, “even so. I do think myself very, very fortunate! And why should I not? I have excellent health, capital spirits, fair abilities, and, bating an occasional outbreak of anger, a reasonably good temper. As regards personal traits, Mr. Annesley Beecher once called me beautiful; Count Lienstahl would say something twice as rapturous; at all events, quite good-looking enough not to raise antipathies against me at first sight; and lastly, but worth all the rest, I have an intense enjoyment in mere existence; the words ‘I live’ are to me, ‘I am happy.’ The alternations of life, its little incidents and adventures, its passing difficulties, are, like the changeful aspects of the seasons, full of interest, full of suggestiveness, calling out qualities of mind and resources of temperament that in the cloudless skies of unbroken prosperity might have lain unused and unknown. And now, sir, no more sneers at my fancied good fortune; for, whatever you may say, I feel it to be real.”

There was that in her manner—a blended energy and grace—which went far deeper into Beecher’s heart than her mere words, and he gazed at her slightly flushed cheek and flashing eyes with something very nearly rapture; and he muttered to himself, “There she is, a half-bred ‘un, and no training, and able to beat them all!”

This time, at all events, she did not read his thoughts; as little, perhaps, did she care to speculate about them. “By the by,” said she, suddenly approaching the chimney and taking up a letter, “this has arrived here, by private hand, since you went out, and it has a half-look of papa’s writing, and is addressed to you.”

Beecher took it eagerly. With a glance he recognized it as from Grog, when that gentleman desired to disguise his hand.

“Am I correct?” asked she,—“am I correct in my guess?”

He was too deep in the letter to make her any reply. Its contents were as follows:—

“Dear B.,—They ‘ve kicked up such a row about that affair at Brussels that I have been obliged to lie dark for the last fortnight, and in a confoundedly stupid hole on the right bank of the Rhine. I sent over Spicer to meet the Baron, and take Klepper over to Nimroeguen and Magdeburg, and some other small places in Prussia. They can pick up in this way a few thousand florins, and keep the mill going. I gave him strict orders not to see my daughter, who must know nothing whatever of these or any like doings. The Baron she might see, for he knows life thoroughly, and if he is not a man of high honor, he can assume the part so well that it comes pretty much to the same thing. As to yourself, you will, on receipt of this, call on a certain Lazarus Stein, Juden Gasse, Nov 41 or 42, and give him your acceptance for two thousand gulden, with which settle your hotel bill, and come on to Bonn, where, at the post-office, you will find a note, with my address. Tramp, you see, has won the Cotteswold, as I prophesied, and ‘Leo the Tenth’ nowhere. Cranberry must have got his soup pretty hot, for he has come abroad, and his wife and the children gone down to Scotland. As to your own affairs, Ford says you are better out of the way; and if anything is to be done in the way of compromise, it must be while you are abroad. He does not think Strich can get the rule, and you must n’t distress yourself for an extra outlawry or two. There will be some trouble about the jewels, but I think even that matter may be arranged also. I hope you keep from the tables, and I look for a strict reckoning as to your expenses, and a stricter book up as regards your care of my daughter. ‘All square’ is the word between pal and pal, and there never was born the man did n’t find that to be his best policy when he dealt with “Your friend, “Christopher Davis. “To while away the time in this dreary dog-hole, I have been sketching out a little plan of a martingale for the roulette-table. There’s only one zero at Homburg, and we can try it there as we go up. There’s a flaw in it after the twelfth ‘pass,’ but I don’t despair of getting over the difficulty. Old Stein, the money-changer, was upwards of thirty years croupier at the Cursaal, and get him to tell you the average runs, black and red, at rouge-et-noir, and what are the signs of an intermitting game; and also the six longest runs he has ever known. He is a shrewd fellow, and seeing that you come from me will be confidential. “There has been another fight in the Crimea, and somebody well licked. I had nothing on the match, and don’t care a brass farthing who claimed the stakes. “Tell Lizey that I ‘m longing to see her, and if I didn’t write it is because I ‘m keeping everything to tell her when we meet. If it was n’t for her picture, I don’t know what would have become of me since last Tuesday, when the rain set in.”

Beecher re-read the letter from the beginning; nor was it an easy matter for him to master at once all the topics it included. Of himself and his own affairs the information was vague and unsatisfactory; but Grog knew how to keep him always in suspense,—to make him ever feel that he was swimming for his life, and he himself the only “spar” he could catch at.

“Bring me to book about my care of his daughter!” muttered he, over and over, “just as if she was n’t the girl to take care of herself. Egad! he seems to know precious little about her. I ‘d give a ‘nap’ to show her this letter, and just hear what she ‘d say of it all. I suppose she ‘d split on me. She ‘d go and tell Davis, ‘Beecher has put me up to the whole “rig;”’ and if she did—What would happen then?” asked he, replying to the low, plaintive whistle which concluded his meditation. “Eh—what! did I say anything?” cried he, in terror.

“Not a syllable. But I could see that you had conjured up some difficulty which you were utterly unable to deal with.”

“Well, here it is,” said he, boldly. “This letter is from your father. It’s all full of private details, of which you know nothing, nor would you care to hear; but there is one passage—just one—that I’d greatly like to have your opinion upon. At the same time I tell you, frankly, I have no warranty from your father to let you see it; nay, the odds are he ‘d pull me up pretty sharp for doing so without his authority.”

“That’s quite enough, Mr. Beecher, about your scruples. Now, mine go a little further still; for they would make me refuse to learn anything which my father’s reserve had kept from me. It is a very easy rule of conscience, and neither hard to remember nor to follow.”

“At all events, he meant this for your own eye,” said Beecher, showing her the last few lines of the letter.

She read them calmly over; a slight trembling of the lip—so slight that it seemed rather like a play of light over her face—was the only sign of emotion visible, and then, carefully folding the letter, she gave it back, saying, “Yes, I had a right to see these lines.”

“He is fond of you, and proud of you, too,” said Beecher. A very slight nod of her head gave an assent to his remark, and she was silent. “We are to leave this at once,” continued he, “and move on to Bonn, where we shall find a letter with your father’s address, somewhere, I take it, in that neighborhood.” He waited, hoping she would say something, but she did not speak. And then he went on:

“And then you will be once more at home,—emancipated from this tiresome guardianship of mine.”

“Why tiresome?” asked she, suddenly.

“Oh, by Jove! I know I’ m very slow sort of fellow as a ladies’ man; have none of the small talents of those foreigners; couldn’t tell Mozart from Verdi; nor, though I can see when a woman is well togged, could I tell you the exact name of any one part of her dress.”

“If you really did know all these, and talked of them, I might have found you very tiresome,” said she, in that half-careless voice she used when seeming to think aloud. “And you,” asked she, suddenly, as she turned her eyes fully upon him,—“and you, are you to be emancipated then,—are you going to leave us?”

“As to that,” replied he, in deep embarrassment, “there ‘a a sort of hitch in it I ought, if I did the right thing, to be on my way to Italy now, to see Lackington,—my brother, I mean. I came abroad for that; but Gr—your father, I should say—induced me to join him, and so, with one thing and the other, here I am, and that’s really all I know about it.”

“What a droll way to go through life!” said she, with one of her low, soft laughs.

“If you mean that I have n’t a will of my own, you ‘re all wrong,” said he, in some irritation. “Put me straight at my fence, and see if I won’t take it. Just say, ‘A. B., there’s the winning-post,’ and mark whether I won’t get my speed up.”

What a strange glance was that which answered this speech! It implied no assent; as little did it mean the reverse. It was rather the look of one who, out of a maze of tangled fancies, suddenly felt recalled to life and its real interests. To poor Beecher’s apprehension it simply seemed a sort of half-compassionate pity, and it made his cheek tingle with wounded pride.

“I know,” muttered he to himself, “that she thinks me a confounded fool; but I ain’t. Many a fellow in the ring made that mistake, and burned his fingers for it after.”

“Well,” said she, after a moment or so of thought, “I am ready; at least, I shall be ready very soon. I ‘ll tell Annette to pack up and prepare for the road.”

“I wish I could get you to have some better opinion of me, Miss Lizzy,” said he, seriously. “I’d give more than I ‘d like to say, that you ‘d—you ‘d—”

“That I’d what?” asked she, calmly.

“That you ‘d not set me down as a regular flat,” said he, with energy.

“I ‘m not very certain that I know what that means; but I will tell you that I think you very good tempered, very gentle-natured, and very tolerant of fifty-and-one caprices which must be all the more wearisome because unintelligible. And then, you are a very fine gentleman, and—the Honor-Able Annesley Beecher.” And holding out her dress in minuet fashion, she courtesied deeply, and left the room.

“I wish any one would tell me whether I stand to win or not by that book,” exclaimed Beecher, as he stood there alone, nonplussed and confounded. “Would n’t she make a stunning actress! By Jove! Webster would give her a hundred a week, and a free benefit!” And with this he went off into a little mental arithmetic, at the end of which he muttered to himself, “And that does not include starring it in the provinces!”

With the air of a man whose worldly affairs went well, he arranged his hair before the glass, put on his hat, gave himself a familiar nod, and went out.

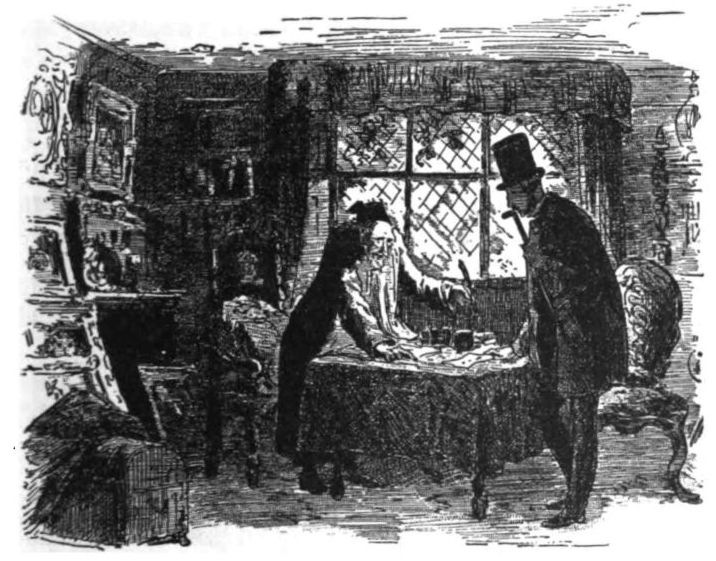

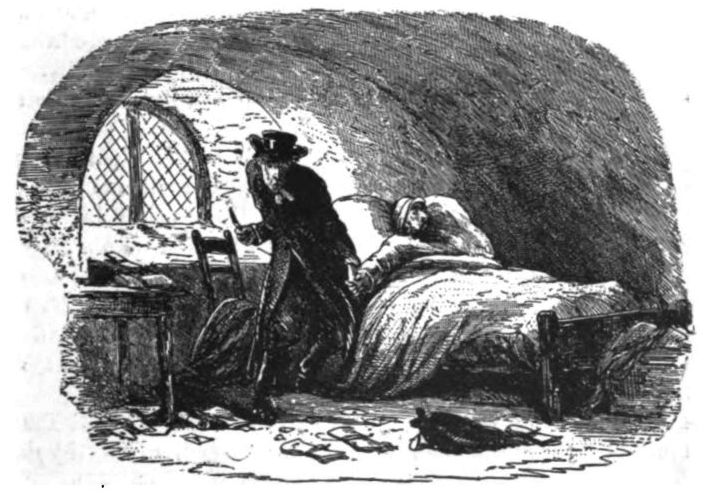

The Juden Gasse, in which Beecher was to find out the residence of Lazarus Stein, was a long, straggling street, beginning in the town and ending in the suburb, where it seemed as it were to lose itself. It was not till after a long and patient search that Beecher discovered a small door in an old ivy-covered wall, on which, in irregular letters, faint and almost illegible, stood the words, “Stein, Geldwechsler.”

As he rang stoutly at the bell, the door opened, apparently of itself, and admitted him into a large and handsome garden. The walks were flanked by fruit-trees in espalier, with broad borders of rich flowers at either side; and although the centre spaces were given up to the uses of a kitchen garden, the larger beds, rich in all the colors of the tulip and ranunculus, showed how predominant was the taste for flowers over mere utility. Up one alley, and down another, did Beecher saunter without meeting any one, or seeing what might mean a habitation; when, at length, in a little copse of palm-trees, he caught sight of a smalt diamond-paned window, approaching which, he found himself in front of a cottage whose diminutive size he had never seen equalled, save on the stage. Indeed, in its wooden framework, gaudily painted, its quaint carvings, and its bamboo roof, it was the very type of what one sees in a comic opera. One sash of the little window lay open, and showed Beecher the figure of a very small old man, who, in a long dressing-gown of red-brown stuff, and a fez cap, was seated at a table, writing. A wooden tray in front of him was filled with dollars and gold pieces in long stately columns, and a heap of bank-notes lay pressed under a heavy leaden slab at his side. No sooner had Beecher’s figure darkened the window than the old man looked up and came out to meet him, and, taking off his cap with a deep reverence, invited him to enter. If the size of the chamber, and its curious walls covered over with cabinet pictures, might have attracted Beecher’s attention at another moment, all his wonderment, now, was for the little man himself, whose piercing black eyes, long beard, and hooked nose gave him an air of almost unearthly meaning.

“I suppose I have the honor to speak to Mr. Stein?” said he, in English, “and that he can understand me in my own tongue?”

“Yaas,—go on,” said the old man.

“I was told to call upon you by Captain Davis; he gave me your address.”

“Ah, der Davis—der Davis—a vaary goot man—my vaary dear friend. You are der rich Englander that do travel wit him,—eh?”

“I am travelling with him just now,” said Beecher, laughing slightly; “but as to being rich,—why, we ‘ll not dispute about it.”

“Yaas, here is his letter. He says, Milord will call on you hisself, and so I hold myself—how you say ‘bereit?’—ready—hold myself ready to see you. I have de honor to make you very mush welcome to my poor house.”

Beecher thanked him courteously, and, producing Davis’s letter, mentioned the amount for which he desired to draw.

The old man examined the writing, the signature, and then the seal, handing the document back when he had finished, muttering to himself, “Ah, der Davis—der Davis!”

“You know my friend very intimately, I believe?” asked Beecher.

“I belief I do,—I belief I do,” said he, with a low chuckle to himself.

“So he mentioned to me and added one or two little matters on which I was to ask you for some information. But first this bill,—you can let me have these two thousand florins?”

“And what do he do now, der Davis?” asked the Jew, not heeding the question.

“Well, I suppose he rubs on pretty much the same as ever,” said Beecher, in some confusion.

“Yaas—yaas—he rub on—and he rub off, too, sometimes—ha! ha! ha!” laughed out the old man, with a fiendish cackle. “Ach, der Davis!”

Without knowing in what sense to take the words, Beecher did not exactly like them; and as little was he pleased with that singular recurrence to “der Davis,” and the little sigh that followed. He was growing impatient, besides, to get his money, and again reverted to the question.

“He look well? I hope he have de goot gesundheit—what you call it?”

“To be sure he does; nothing ever ails him. I never heard him complain of as much as a headache.

“Ach, der Davis, der Davis!” said the old man, shaking his head.

Seeing no chance of success by his direct advances, Beecher thought he ‘d try a little flank attack by inducing a short conversation, and so he said, “I am on my way to Davis, now, with his daughter, whom he left in my charge.”

“Whose daughter?” asked the Jew.

“Davis’s,—a young lady that was educated at Brussels.”

“He have no daughter. Der Davis have no daughter.”

“Has n’t he, though? Just come over to the ‘Four Nations,’ and I ‘ll show her to you. And such a stunning girl too!”

“No, no, I never belief it—never; he did never speak to me of a daughter.”

“Whether he did or not—there she is, that’s all I know.”

The Jew shook his head, and sought refuge in his former muttering of “Ach, der Davis!”

“As far as not telling you about his daughter, I can say he never told me, and I fancy we were about as intimate as most people; but the fact is as I tell you.”

Another sigh was all his answer, and Beecher was fast reaching the limit of his patience.

“Daughter, or no daughter, I want a matter of a couple of thousand florins,—no objection to a trifle more, of course,—and wish to know how you can let me have them.”

“The Margraf was here two week ago, and he say to me, ‘Lazarus,’ say he,—‘Lazarus, where is your goot friend Davis?’ ‘Highness,’ say I, ‘dat I know not.’ Den he say, ‘I will find him, if I go to Jerusalem;’ and I say, ‘Go to Jerusalem.’”

“What did he want with him?”

“What he want?—what every one want, and what nobody get, except how he no like—ha! ha! ha! Ach, der Davis!”

Beecher rose from his seat, uncertain how to take this continued inattention to his demand. He stood for a moment in hesitation, his eyes wandering over the walls where the pictures were hanging.

“Ah! if you do care for art, now you suit yourself, and all for a noting! I sell all dese,—dat Gerard Dow, dese two Potters, de leetle Cuyp,—a veritable treasure, and de Mieris,—de best he ever painted, and de rest, wit de land-schaft of Both, for eighty tousand seven hundred florins. It is a schenk—a gift away—noting else.”

“You forget, my excellent friend Stein,” said Beecher, with more assurance than he had yet assumed, “that it was to receive and not spend money I came here this morning.”

“You do a leetle of all de two—a leetle of both, so to say,” replied the Jew. “What moneys you want?”

“Come, this is speaking reasonably. Davis’s letter mentions a couple of thousand florins; but if you are inclined to stretch the amount to five, or even four thousand, we ‘ll not fall out about the terms.”

“How you mean—no fall out about de terms?” said the other, sharply.

“I meant that for a stray figure or so, in the way of discount, we should n’t disagree. You may, in fact, make your own bargain.”

“Make my own bargain, and pay myself too,” muttered the Jew. “Ach, der Davis, how he would laugh!—ha! ha! ha!”

“Well, I don’t see much to laugh at, old gent, except it be at my own folly, to stand here so long chaffering about these paltry two thousand florins. And now I say, ‘Yea or nay, will you book up, or not?’”

“Will you buy de Cuyp and de Wouvermans and de Ostade?—dat is the question.”

“Egad, if you furnish the ready, I ‘ll buy the Cathedral and the Cursaal. I ‘m not particular as to the investment when the cash is easily come at.”

“De cash is very easy to come at,” said the Jew, with a strange grin.

“You ‘re a trump, Lazarus!” cried Beecher, in ecstasy at his good fortune. “If I had known you some ten years ago, I ‘d have been another man to-day. I was always looking out for one really fair, honester-hearted fellow to deal with, but I never met with him till now.”

“How you have it,—gold or notes?” said Lazarus.

“Well, a little of both, I think,” said Beecher, his eyes greedily devouring the glittering little columns of gold before him.

“How your title?—how your name?” asked Stein, taking up a pen.

“My name is Annesley Beecher. You may write me the ‘Honorable Annesley Beecher.’”

“Lord of—”

“I ‘m not Lord of anything. I’m next in succession to a peerage, that’s all.”

“He call you de Viscount—I forget de name.”

“Lackington, perhaps?”

“Yaas, dat is de name; and say, give him de moneys for his bill. Now, here is de acceptance, and here you put your sign, across dis.”

“I ‘ll write Annesley Beecher, with all my heart; but I ‘ll not write myself Lackington.”

“Den you no have de moneys, nor de Cuyp, nor de Ostade,” said the Jew, replacing the pen in the ink-bottle.

“Just let me ask you, old boy, how would it benefit you that I should commit a forgery? Is that the way you like to do business?”

“I do know myself how I like my business to do, and no man teach me.”

“What the devil did Davis mean, then, by sending me on this fool’s errand? He gave me a distinct intimation that you ‘d cash my acceptance—”

“Am I not ready? You never go and say to der Davis dat I refuse it! Ah, der Davis!” and he sighed as if from the very bottom of his heart.

“I’ll tell him, frankly, that you made it a condition I was to sign a name that does not belong to me,—that I ‘ll tell him.”

“What care he for dat? Der Davis write his own name on it and pay it hisself.”

“Oh! and Davis was also to indorse this bill, was he?” asked Beecher.

“I should tink he do; oderwise I scarce give you de moneys.”

“That, indeed, makes some difference. Not, in reality, that it would n’t be just as much a forgery; but if the bill come back to Grog’s own hands—”

“Ach, der Grog,—ha! ha! ha! ‘Tis so long dat I no hear de name,—Grog Davis!” and the Jew laughed till his eyes ran over.

“If there’s no other way of getting at this money—”

“Dere is no oder way,” said Lazarus, in a tone of firmness..

“Then good-morning, friend Lazarus, for you ‘ll not catch me spoiling a stamp at that price. No, no, old fellow. I ‘m up to a thing or two, though you don’t suspect it. I only rise to the natural fly, and no mistake.”

“I make no mistake; I take vaary goot care of dat,” said Lazarus, rising, and taking off his fez, to say adieu. “I wish you de vaary goot day.”

Beecher turned away, with a stiff salutation, into the garden. He was angry with Davis, with himself, and with the whole world. It was a rare event in his life to see gold so much within his reach and yet not available, just for a scruple—a mere scruple—for, after all, what was it else? Writing “Lackington” meant nothing, if Lack-ington were never to see, much less to pay the bill. Once “taken up,” as it was sure to be by Grog, what signified it if the words across the acceptance were Lackington or Annesley Beecher? And yet, what could Davis mean by passing him off as the Viscount? Surely, for such a paltry sum as a couple of thousand florins, it was not necessary to assume his brother’s name and title. It was some “dodge,” perhaps, to acquire consequence in the eyes of his friend Lazarus that he was the travelling-companion of an English peer; and yet, if so, it was the very first time Beecher had known him yield to such a weakness. He had a meaning in it, that much was certain, for Grog made no move in the game of life without a plan! “It can’t be,” muttered Beecher to himself,—“it can’t be for the sake of any menace over me for the forgery, because he has already in his hands quite enough to push me to the wall on that score, as he takes care to remind me he might any fine morning have me ‘up’ on that charge.” The more Beecher ruminated over what possible intention Davis might have in view, the more did he grow terrified, lest, by any short-comings on his own part, he might thwart the great plans of his deep colleague.