The Project Gutenberg EBook of St. Patrick's Eve, by Charles James Lever This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: St. Patrick's Eve Author: Charles James Lever Illustrator: Phiz. Release Date: April 21, 2010 [EBook #32083] Last Updated: September 3, 2016 Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ST. PATRICK'S EVE *** Produced by David Widger

There are few things less likely than that it will ever be your lot to exercise any of the rights or privileges of landed property. It may chance, however, that even in your humble sphere, there may be those who shall look up to you for support, and be, in some wise, dependent on your will; if so, pray let this little story have its lesson in your hearts, think, that when I wrote it, I desired to inculcate the truth, that prosperity has as many duties as adversity has sorrows; that those to whom Providence has accorded many blessings are but the stewards of His bounty to the poor; and that the neglect of an obligation so sacred as this charity is a grievous wrong, and may be the origin of evils for which all your efforts to do good through life will be but a poor atonement.

Your affectionate Father,

CHARLES LEVER.

Templeogue, March 1, 1845.

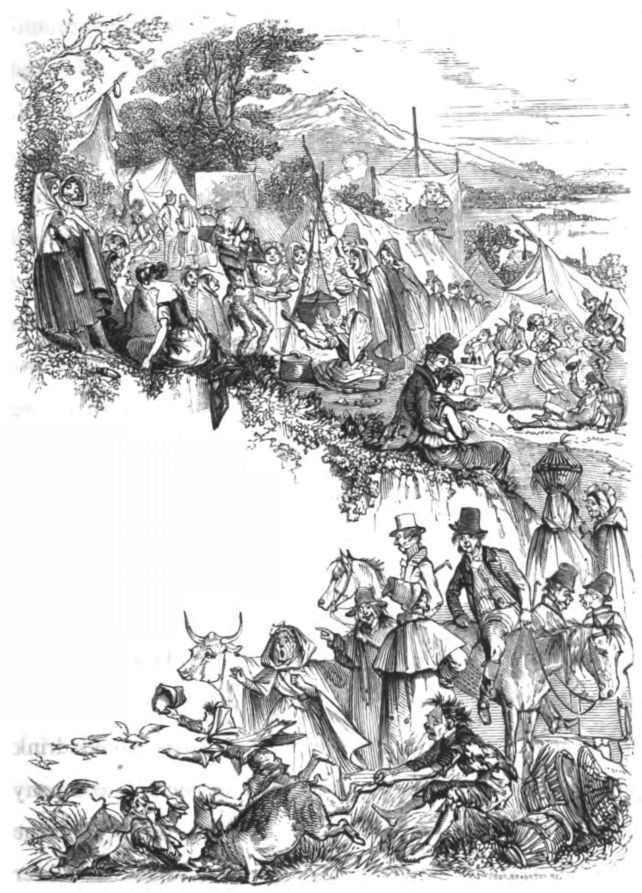

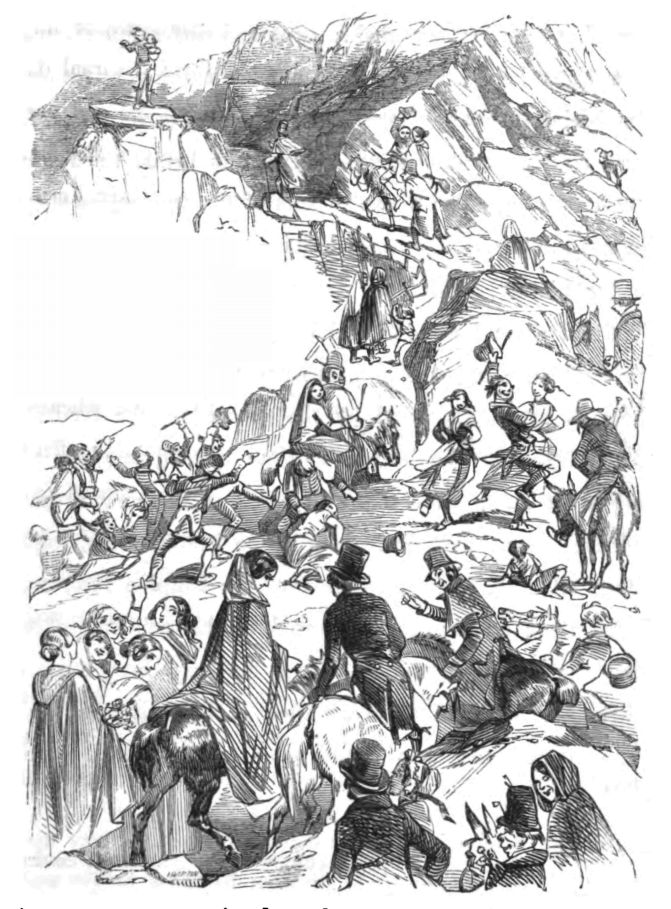

IT was on the 16th of March, the eve of St. Patrick, not quite twenty years ago, that a little village on the bank of Lough Corrib was celebrating in its annual fair “the holy times,” devoting one day to every species of enjoyment and pleasure, and on the next, by practising prayers and penance of various kinds, as it were to prepare their minds to resume their worldly duties in a frame of thought more seemly and becoming.

If a great and wealthy man might smile at the humble preparations for pleasure displayed on this occasion, he could scarcely scoff at the scene which surrounded them. The wide valley, encircled by lofty mountains, whose swelling outlines were tracked against the blue sky, or mingled gracefully with clouds, whose forms were little less fantastic and wild. The broad lake, stretching away into the distance, and either lost among the mountain-passes, or contracting as it approached the ancient city of Galway: a few, and but very few, islands marked its surface, and these rugged and rocky; on one alone a human trace was seen-the ruins of an ancient church; it was a mere gable now, but you could still track out the humble limits it had occupied-scarce space sufficient for twenty persons: such were once, doubtless, the full number of converts to the faith who frequented there. There was a wild and savage grandeur in the whole: the very aspect of the mountains proclaimed desolation, and seemed to frown defiance at the efforts of man to subdue them to his use; and even the herds of wild cattle seemed to stray with caution among the cliffs and precipices of this dreary region. Lower down, however, and as if in compensation of the infertile tract above, the valley was marked by patches of tillage and grass-land, and studded with cottages; which, if presenting at a nearer inspection indubitable signs of poverty, yet to the distant eye bespoke something of rural comfort, nestling as they often did beneath some large rock, and sheltered by the great turf-stack, which even the poorest possessed. Many streams wound their course through this valley; along whose borders, amid a pasture brighter than the emerald, the cattle grazed, and there, from time to time some peasant child sat fishing as he watched the herd.

Shut in by lake and mountain, this seemed a little spot apart from all the world; and so, indeed, its inhabitants found it. They were a poor but not unhappy race of people, whose humble lives had taught them nothing of the comforts and pleasures of richer communities. Poverty had, from habit, no terrors for them; short of actual want, they never felt its pressure heavily.

Such were they who now were assembled to celebrate the festival of their Patron Saint. It was drawing towards evening; the sun was already low, and the red glare that shone from behind the mountains shewed that he was Bear his setting. The business of the fair was almost concluded; the little traffic so remote a region could supply, the barter of a few sheep, the sale of a heifer, a mountain pony, or a flock of goats, had all passed off; and now the pleasures of the occasion were about to succeed. The votaries to amusement, as if annoyed at the protracted dealings of the more worldly minded, were somewhat rudely driving away the cattle that still continued to linger about; and pigs and poultry were beginning to discover that they were merely intruders. The canvass booths, erected as shelter against the night-air, were becoming crowded with visitors; and from more than one of the number the pleasant sounds of the bagpipe might now be heard, accompanied by the dull shuffling tramp of heavily-shod feet.

Various shows and exhibitions were also in preparation, and singular announcements were made by gentlemen in a mingled costume of Turk and Thimble-rigger, of “wonderful calves with two heads;” “six-legged pigs;” and an “infant of two years old that could drink a quart of spirits at a draught, if a respectable company were assembled to witness it;”—a feat which, for the honour of young Ireland, it should be added, was ever postponed from a deficiency in the annexed condition.

Then there were “restaurants” on a scale of the most primitive simplicity, where boiled beef or “spoleen” was sold from a huge pot, suspended over a fire in the open air, and which was invariably surrounded by a gourmand party of both sexes; gingerbread and cakes of every fashion and every degree of indigestion also abounded; while jugs and kegs flanked the entrance to each tent, reeking with a most unmistakable odour of that prime promoter of native drollery and fun—poteen. All was stir, movement, and bustle; old friends, separated since the last occasion of a similar festivity, were embracing cordially, the men kissing with an affectionate warmth no German ever equalled; pledges of love and friendship were taken in brimming glasses by many, who were perhaps to renew the opportunity for such testimonies hereafter, by a fight that very evening; contracts, ratified by whisky, until that moment not deemed binding; and courtships, prosecuted with hopes, which the whole year previous had never suggested; kind speeches and words of welcome went round; while here and there some closely-gathered heads and scowling glances gave token, that other scores were to be acquitted on that night than merely those of commerce; and in the firmly knitted brow, and more firmly grasped blackthorn, a practised observer could foresee, that some heads were to carry away deeper marks of that meeting, than simple memory can impress;—and thus, in this wild sequestered spot, human passions were as rife as in the most busy communities of pampered civilisation. Love, hate, and hope, charity, fear, forgiveness, and malice; long-smouldering revenge, long—subdued affection; hearts pining beneath daily drudgery, suddenly awakened to a burst of pleasure and a renewal of happiness in the sight of old friends, for many a day lost sight of; words of good cheer; half mutterings of menace; the whispered syllables of love; the deeply-uttered tones of vengeance; and amid all, the careless reckless glee of those, who appeared to feel the hour one snatched from the grasp of misery, and devoted to the very abandonment of pleasure. It seemed in vain that want and poverty had shed their chilling influence over hearts like these. The snow-drift and the storm might penetrate their frail dwellings; the winter might blast, the hurricane might scatter their humble hoardings; but still, the bold high-beating spirit that lived within, beamed on throughout every trial; and now, in the hour of long-sought enjoyment, blazed forth in a flame of joy, that was all but frantic.

The step that but yesterday fell wearily upon the ground, now smote the earth with a proud beat, that told of manhood’s daring; the voices were high, the eyes were flashing; long pent-up emotions of every shade and complexion were there; and it seemed a season where none should wear disguise, but stand forth in all the fearlessness of avowed resolve; and in the heart-home looks of love, as well as in the fiery glances of hatred, none practised concealment. Here, went one with his arm round his sweetheart’s waist,—an evidence of accepted affection none dared even to stare at; there, went another, the skirt of his long loose coat thrown over his arm, in whose hand a stick was brandished—his gesture, even without his wild hurroo! an open declaration of battle, a challenge to all who liked it. Mothers were met in close conclave, interchanging family secrets and cares; and daughters, half conscious of the parts they themselves were playing in the converse, passed looks of sly intelligence to each other. And beggars were there too—beggars of a class which even the eastern Dervish can scarcely vie with: cripples brought many a mile away from their mountain-homes to extort charity by exhibitions of dreadful deformity; the halt, the blind, the muttering idiot, the moping melanc holy mad, mixed up with strange and motley figures in patched uniforms and rags—some, amusing the crowd by their drolleries, some, singing a popular ballad of the time—while through all, at every turn and every corner, one huge fellow, without legs, rode upon an ass, his wide chest ornamented by a picture of himself, and a paragraph setting forth his infirmities. He, with a voice deeper than a bassoon, bellowed forth his prayer for alms, and seemed to monopolise far more than his proportion of charity, doubtless owing to the more artistic development to which he had brought his profession.

“De prayers of de holy Joseph be an yez, and relieve de maimed; de prayers and blessins of all de Saints on dem that assists de suffering!” And there were pilgrims, some with heads venerable enough for the canvass of an old master, with flowing beards, and relics hung round their necks, objects of worship which failed not to create sentiments of devotion in the passers-by. But among these many sights and sounds, each calculated to appeal to different classes and ages of the motley mass, one object appeared to engross a more than ordinary share of attention; and although certainly not of a nature to draw marked notice elsewhere, was here sufficiently strange and uncommon to become actually a spectacle. This was neither more nor less than an English groom, who, mounted upon a thorough-bred horse, led another by the bridle, and slowly paraded backwards and forwards, in attendance on his master.

“Them’s the iligant bastes, Darby,” said one of the bystanders, as the horses moved past. “A finer pair than that I never seen.”

“They’re beauties, and no denying it,” said the other; “and they’ve skins like a looking-glass.”

“Arrah, botheration t’ yez! what are ye saying about their skins?” cried a third, whose dress and manner betokened one of the jank of a small farmer. “‘Tis the breeding that’s in ‘em; that’s the raal beauty. Only look at their pasterns; and see how fine they run off over the quarter.”

“Which is the best now, Phil?” said another, addressing the last speaker with a tone of some deference.

“The grey horse is worth two of the dark chesnut,” replied Phil oracularly.

“Is he, then!” cried two or three in a breath. “Why is that, Phil?”

“Can’t you perceive the signs of blood about the ears? They’re long, and coming to a point—”

“You’re wrong this time, my friend,” said a sharp voice, with an accent which in Ireland would be called English. “You may be an excellent judge of an ass, but the horse you speak of, as the best, is not worth a fourth part of the value of the other.” And so saying, a young and handsome man, attired in a riding costume, brushed somewhat rudely through the crowd, and seizing the rein of the led horse, vaulted lightly into the saddle and rode off, leaving Phil to the mockery and laughter of the crowd, whose reverence for the opinion of a gentleman was only beneath that they accorded to the priest himself.

“Faix, ye got it there, Phil!” “‘Tis down on ye he was that time!” “Musha, but ye may well get red in the face!” Such and such-like were the comments on one who but a moment before was rather a popular candidate for public honours.

“Who is he, then, at all?” said one among the rest, and who had come up too late to witness the scene.

“‘Tis the young Mr. Leslie, the landlord’s son, that’s come over to fish the lakes,” replied an old man reverentially.

“Begorra, he’s no landlord of mine, anyhow,” said Phil, now speaking for the first time. “I hould under Mister Martin, and his family was here before the Leslies was heard of.” These words were said with a certain air of defiance, and a turn of the head around him, as though to imply, that if any one would gainsay the opinion, he was ready to stand by and maintain it. Happily for the peace of the particular moment, the crowd were nearly all Martins, and so, a simple buzz of approbation followed this announcement. Nor did their attention dwell much longer on the matter, as most were already occupied in watching the progress of the young man, who, at a fast swinging gallop, had taken to the fields beside the lake, and was now seen flying in succession over each dyke and wall before him, followed by his groom. The Irish passion for feats of horsemanship made this the most fascinating attraction of the fair; and already, opinions ran high among the crowd, that it was a race between the two horses, and more than one maintained, that “the little chap with the belt” was the better horseman of the two. At last, having made a wide circuit of the village and the green, the riders were seen slowly moving down, as if returning to the fair.

There is no country where manly sports and daring exercises are held in higher repute than Ireland. The chivalry that has died out in richer lands still reigns there; and the fall meed of approbation will ever be his, who can combine address and courage before an Irish crowd. It is needless to say, then, that many a word of praise and commendation was bestowed on young Leslie. His handsome features, his slight but well-formed figure, every particular of his dress and gesture, had found an advocate and an admirer; and while some were lavish in their epithets on the perfection of his horsemanship, others, who had seen him on foot, asserted, “that it was then he looked well entirely.” There is a kind of epidemic character pertaining to praise. The snow-ball gathers not faster by rolling, than do the words of eulogy and approbation; and so now, many recited little anecdotes of the youth’s father, to shew that he was a very pattern of landlords and country gentlemen, and had only one fault in life,—that he never lived among his tenantry.

“‘Tis the first time I ever set eyes on him,” cried one, “and I hould my little place under him twenty-three years come Michaelmas.”

“See now then, Barney,” cried another, “I’d rather have a hard man that would stay here among us, than the finest landlord ever was seen that would be away from us. And what’s the use of compassion and pity when the say would be between us? ‘Tis the Agent we have to look to.”

“Agent! ‘Tis wishing them, I am, the same Agents! Them’s the boys has no marcy for a poor man: I’m tould now”—and here the speaker assumed a tone of oracular seriousness that drew several listeners towards him—“I’m tould now, the Agents get a guinea for every man, woman, and child they turn out of a houldin.” A low murmur of indignant anger ran through the group, not one of whom ventured to disbelieve a testimony thus accredited.

“And sure when the landlords does come, devil a bit they know about us—no more nor if we were in Swayden; didn’t I hear the ould gentleman down there last summer, pitying the people for the distress. ‘Ah,’ says he, it’s a hard sayson ye have, and obliged to tear the flax out of the ground, and it not long enough to cut!’”

A ready burst of laughter followed this anecdote, and many similar stories were recounted in corroboration of the opinion.

“That’s the girl takes the shine out of the fair,” said one of the younger men of the party, touching another by the arm, and pointing to a tall young girl, who, with features as straight and regular as a classic model, moved slowly past. She did not wear the scarlet cloak of the peasantry, but a large one of dark blue, lined with silk of the same colour; a profusion of brown hair, dark and glossy, was braided on each side of her face, and turned up at the back of the head with the grace of an antique cameo. She seemed not more than nineteen years of age, and in the gaze of astonishment and pleasure she threw around her, it might be seen how new such scenes and sights were to her.

“That’s Phil Joyce’s sister, and a crooked disciple of a brother she has,” said the other; “sorra bit if he’d ever let her come to the ‘pattern’ afore to-day; and she’s the raal ornament of the place now she’s in it.”

“Just mind Phil, will ye! watch him now; see the frown he’s giving the boys as they go by, for looking at his sister. I wouldn’t coort a girl that I couldn’t look in the face and see what was in it, av she owned Ballinahinch Castle,” said the former.

“There now; what is he at now?” whispered the other; “he’s left her in the tent there: and look at him, the way he’s talking to ould Bill; he’s telling him something about a fight; never mind me agin, but there’ll be wigs on the green’ this night.”

“I don’t know where the Lynchs and the Connors is to-day,” said the other, casting a suspicious look around him, as if anxious to calculate the forces available in the event of a row. “They gave the Joyces their own in Ballinrobe last fair. I hope they’re not afeard to come down here.”

“Sorra bit, ma bouchai,” said a voice from behind his shoulder; and at the same moment the speaker clapped his hands over the other’s eyes: “Who am I, now?”

“Arrah! Owen Connor; I know ye well,” said the other; “and His yourself ought not to be here to-day. The ould father of ye has nobody but yourself to look after him.”

“I’d like to see ye call him ould to his face,” said Owen, laughing: “there he is now, in Poll Dawley’s tent, dancing.”

“Dancing!” cried the other two in a breath.

“Aye, faix, dancing ‘The little bould fox;’ and may I never die in sin, if he hasn’t a step that looks for all the world as if he made a hook and eye of his legs.”

The young man who spoke these words was in mould and gesture the very ideal of an Irish peasant of the west; somewhat above the middle size, rather slightly made, but with the light and neatly turned proportion that betokens activity, more than great strength, endurance, rather than the power of any single effort. His face well became the character of his figure; it was a handsome and an open one, where the expressions changed and crossed each other with lightning speed, now, beaming with good nature, now, flashing in anger, now, sparkling with some witty conception, or frowning a bold defiance as it met the glance of some member of a rival faction. He looked, as he was, one ready and willing to accept either part from fortune, and to exchange friendship and hard knocks with equal satisfaction. Although in dress and appearance he was both cleanly and well clad, it was evident that he belonged to a very humble class among the peasantry. Neither his hat nor his greatcoat, those unerring signs of competence, had been new for many a day before; and his shoes, in their patched and mended condition, betrayed the pains it had cost him to make even so respectable an appearance as he then presented.

“She didn’t even give you a look to-day, Owen,” said one of the former speakers; “she turned her head the other way as she went by.”

“Faix, I’m afeard ye’ve a bad chance,” said the other.

“Joke away, boys, and welcome,” said Owen, reddening to the eyes as he spoke, and shewing that his indifference to their banterings was very far from being real; “‘tis little I mind what ye say,—as little as she herself would mind me,” added he to himself.

“She’s the purtiest girl in the town-land, and no second word to it,—and even if she hadn’t a fortune—”

“Bad luck to the fortune!—that’s what I say,” cried Owen, suddenly; “‘tis that same that breaks my rest night and day; sure if it wasn’t for the money, there’s many a dacent boy wouldn’t be ashamed nor afeard to go up and coort her.”

“She’ll have two hundred, divil a less, I’m tould,” interposed the other; “the ould man made a deal of money in the war-time.”

“I wish he had it with him now,” said Owen, bitterly.

“By all accounts he wouldn’t mislike it himself. When Father John was giving him the rites, he says, ‘Phil,’ says he, ‘how ould are ye now?’ and the other didn’t hear him, but went on muttering to himself; and the Priest says agin, ‘Tis how ould you are, I’m axing.’ ‘A hundred and forty-three,’ says Phil, looking up at him. ‘The Saints be good to us,’ says Father John, ‘sure you’re not that ould,—a hundred and forty-three?’ ‘A hundred and forty-seven.’ ‘Phew! he’s more of it—a hundred and forty-seven!’ ‘A hundred and fifty,’ cries Phil, and he gave the foot of the bed a little kick, this way—sorra more—and he died; and what was it but the guineas he was countin’ in a stocking under the clothes all the while? Oh, musha! how his sowl was in the money, and he going to leave it all! I heerd Father John say, ‘it was well they found it out, for there’d be a curse on them guineas, and every hand that would touch one of them in secla seclorum;’ and they wer’ all tuck away in a bag that night, and buried by the Priest in a saycret place, where they’ll never be found till the Day of Judgment.”

Just as the story came to its end, the attention of the group was drawn off by seeing numbers of people running in a particular direction, while the sound of voices and the general excitement shewed something new was going forward. The noise increased, and now, loud shouts were heard, mingled with the rattling of sticks and the utterance of those party cries so popular in an Irish fair. The young men stood still as if the affair was a mere momentary ebullition not deserving of attention, nor sufficiently important to merit the taking any farther interest in it; nor did they swerve from the resolve thus tacitly formed, as from time to time some three or four would emerge from the crowd, leading forth one, whose bleeding temples, or smashed head, made retreat no longer dishonourable.

“They’re at it early,” was the cool commentary of Owen Connor, as with a smile of superciliousness he looked towards the scene of strife.

“The Joyces is always the first to begin,” remarked one of his companions.

“And the first to lave off too,” said Owen; “two to one is what they call fair play.”

“That’s Phil’s voice!—there now, do you hear him shouting?”

“‘Tis that he’s best at,” said Owen, whose love for the pretty Mary Joyce was scarcely equalled by his dislike of her ill-tempered brother.

At this moment the shouts became louder and wilder, the screams of the women mingling with the uproar, which no longer seemed a mere passing skirmish, but a downright severe engagement.

“What is it all about, Christy?” said Owen, to a young fellow led past between two friends, while the track of blood marked every step he went.

“‘Tis well it becomes yez to ax,” muttered the other, with his swollen and pallid lips, “when the Martins is beating your landlord’s eldest son to smithereens.”

“Mr. Leslie—young Mr. Leslie?” cried the three together; but a wild war-whoop from the crowd gave the answer back. “Hurroo! Martin for ever! Down with the Leslies! Ballinashough! Hurroo! Don’t leave one of them living! Beat their sowles out!”

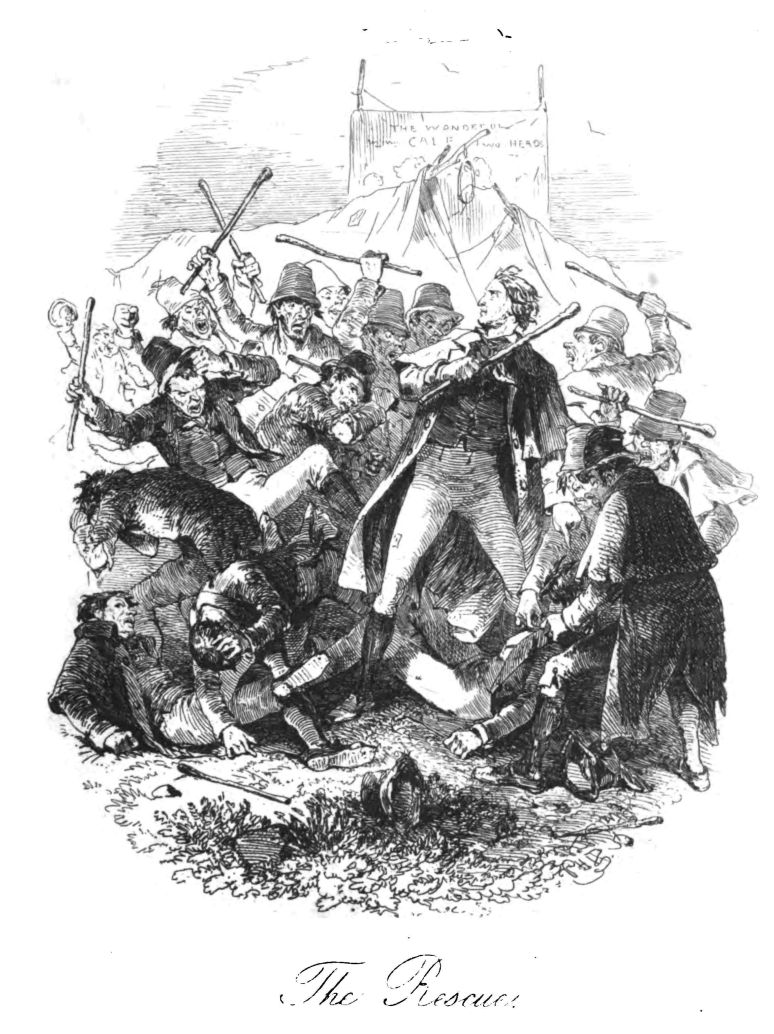

“Leslie for ever!” yelled out Owen, with a voice heard over every part of the field; and with a spring into the air, and a wild flourish of his stick, he dashed into the crowd.

“Here’s Owen Connor, make way for Owen;” cried the non-combatants, as they jostled and parted each other, to leave a free passage for one whose prowess was well known.

“He’ll lave his mark on some of yez yet!” “That’s the boy will give you music to dance to!” “Take that, Barney!” “Ha! Terry, that made your nob ring like a forty-shilling pot!” Such and such-like were the comments on him who now, reckless of his own safety, rushed madly into the very midst of the combatants, and fought’ his way onwards to where some seven or eight were desperately engaged over the fallen figure of a man. With a shrill yell no Indian could surpass, and a bound like a tiger, Owen came down in the midst of them, every stroke of his powerful blackthorn telling on his man as unerringly as though it were wielded by the hand of a giant.

“Save the young Master, Owen! Shelter him! Stand over him, Owen Connor!” were how the cries from all sides; and the stout-hearted peasant, striding over the body of young Leslie, cleared a space around him, and, as he glanced defiance on all sides, called out, “Is that your courage, to beat a young gentleman that never handled a stick in his life? Oh, you cowardly set! Come and face the men of your own barony if you dare! Come out on the green and do it!—Pull him away—pull him away quick,” whispered he to his own party eagerly. “Tear-an-ages! get him out of this before they’re down on me.”

As he spoke, the Joyces rushed forward with a cheer, their party now trebly as strong as the enemy. They bore down with a force that nothing could resist. Poor Owen—the mark for every weapon—fell almost the first, his head and face one undistinguishable mass of blood and bruises, but not before some three or four of his friends had rescued young Leslie from his danger, and carried him to the outskirts of the fair. The fray now became general, neutrality was impossible, and self-defence almost suggested some participation in the battle. The victory was, however, with the Joyces. They were on their own territory; they mustered every moment stronger; and in less than half an hour they had swept the enemy from the field, save where a lingering wounded man remained, whose maimed and crippled condition had already removed him from all the animosities of combat.

“Where’s the young master?” were the first words Owen Connor spoke, as his friends carried him on the door of a cabin, hastily unhinged for the purpose, towards his home.

“Erra! he’s safe enough, Owen,” said one of his bearers, who was by no means pleased that Mr. Leslie had made the best of his way out of the fair, instead of remaining to see the fight out.

“God be praised for that same, anyhow!” said Owen piously. “His life was not worth a ‘trawneen’ when I seen him first.”

It may be supposed from this speech, and the previous conduct of him who uttered it, that Owen Connor was an old and devoted adherent of the Leslie family, from whom he had received many benefits, and to whom he was linked by long acquaintance. Far from it. He neither knew Mr. Leshe nor his father. The former he saw for the first time as he stood over him in the fair; the latter he had never so much as set eyes upon, at any time; neither had he or his been favoured by them. The sole tie that subsisted between them—the one link that bound the poor man to the rich one—was that of the tenant to his landlord. Owen’s father and grandfather before him had been cottiers on the estate; but being very poor and humble men, and the little farm they rented, a half-tilled half-reclaimed mountain tract, exempt from all prospect of improvement, and situated in a remote and unfrequented place, they were merely known by their names on the rent-roll. Except for this, their existence had been as totally forgotten, as though they had made part of the wild heath upon the mountain.

While Mr. Leslie lived in ignorance that such people existed on his property, they looked up to him with a degree of reverence almost devotional. The owner of the soil was a character actually sacred in their eyes; for what respect and what submission were enough for one, who held in his hands the destinies of so many; who could raise them to affluence, or depress them to want, and by his mere word control the Agent himself, the most dreaded of all those who exerted an influence on their fortunes?

There was a feudalism, too, in this sentiment that gave the reverence a feeling of strong allegiance. The landlord was the head of a clan, as it were; he was the culminating point of that pyramid of which they formed the base; and they were proud of every display of his wealth and his power, which they deemed as ever reflecting credit upon themselves. And then, his position in the county—his rank—his titles—the amount of his property—his house—his retinue—his very equipage, were all subjects on which they descanted with eager delight, and proudly exalted in contrast with less favoured proprietors. At the time we speak of, absenteeism had only begun to impair the warmth of this affection; the traditions of a resident landlord were yet fresh in the memory of the young; and a hundred traits of kindness and good-nature were mingled in their minds with stories of grandeur and extravagance, which, to the Irish peasant’s ear, are themes as grateful as ever the gorgeous pictures of Eastern splendour were to the heightened imagination and burning fancies of Oriental listeners.

Owen Connor was a firm disciple of this creed. Perhaps his lone sequestered life among the mountains, with no companionship save that of his old father, had made him longer retain these convictions in all their force, than if, by admixture with his equals, and greater intercourse with the world, he had conformed his opinions to the gradually changed tone of the country. It was of little moment to him what might be the temper or the habits of his landlord. The monarchy—and not the monarch of the soil—was the object of his loyalty; and he would have deemed himself disgraced and dishonoured had he shewn the slightest backwardness in his fealty. He would as soon have expected that the tall fern that grew wild in the valley should have changed into a blooming crop of wheat, as that the performance of such a service could have met with any requital. It was, to his thinking, a simple act of duty, and required not any prompting of high principle, still less any suggestion of self-interest. Poor Owen, therefore, had not even a sentiment of heroism to cheer him, as they bore him slowly along, every inequality of the ground sending a pang through his aching head that was actually torture.

“That’s a mark you’ll carry to your dying day, Owen, my boy,” said one of the bearers, as they stopped for a moment to take breath. “I can see the bone there shining this minute.”

“It must be good stuff anyways the same head,” said Owen, with a sickly attempt to smile. “They never put a star in it yet; and faix I seen the sticks cracking like dry wood in the frost.”

“It’s well it didn’t come lower down,” said another, examining the deep cut, which gashed his forehead from the hair down to the eyebrow. “You know what the Widow Glynn said at Peter Henessy’s wake, when she saw the stroke of the scythe that laid his head open—it just come, like yer own, down to that—‘Ayeh!’ says she, ‘but he’s the fine corpse; and wasn’t it the Lord spared his eye!’”

“Stop, and good luck to you, Freney, and don’t be making me laugh; the pain goes through my brain like the stick of a knife,” said Owen, as he lifted his trembling hands and pressed them on either side of his head.

They wetted his lips with water, and resumed their way, not speaking aloud as before, but in a low undertone, only audible to Owen at intervals; for he had sunk into a half-stupid state, they believed to be sleep. The path each moment grew steeper; for, leaving the wild “boreen” road, which led to a large bog on the mountainside, it wound now upwards, zigzaging between masses of granite rock and deep tufts of heather, where sometimes the foot sunk to the instep. The wet and spongy soil increased the difficulty greatly; and although all strong and powerful men, they were often obliged to halt and rest themselves.

“It’s an elegant view, sure enough,” said one, wiping his dripping forehead with the tail of his coat. “See there! look down where the fair is, now! it isn’t the size of a good griddle, the whole of it. How purty the lights look shining in the water!”

“And the boats, too! Musha! they’re coming up more of them. There’ll be good divarshin there, this night.” These last words, uttered with a half sigh, shewed with what a heavy heart the speaker saw himself debarred from participating in the festivity.

“‘Twas a dhroll place to build a house then, up there,” said another, pointing to the dark speck, far, far away on the mountain, where Owen Connor’s cabin stood.

“Owen says yez can see Galway of a fine day, and the boats going out from the Claddagh; and of an evening, when the sun is going down, you’ll see across the bay, over to Clare, the big cliffs of Mogher.”

“Now, then! are ye in earnest? I don’t wonder he’s so fond of the place after all. It’s an elegant thing to see the whole world, and fine company besides. Look at Lough Mask! Now, boys, isn’t that beautiful with the sun on it?”

“Come, it’s getting late, Freney, and the poor boy ought to be at home before night;” and once more they lifted their burden and moved forward.

For a considerable time they continued to ascend without speaking, when one of the party in a low cautious voice remarked, “Poor Owen will think worse of it, when he hears the reason of the fight, than for the cut on the head—bad as it is.”

“Musha; then he needn’t,” replied another; “for if ye mane about Mary Joyce, he never had a chance of her.”

“I’m not saying that he had,” said the first speaker; “but he’s just as fond of her; do you mind the way he never gave back one of Phil’s blows, but let him hammer away as fast as he plazed?”

“What was it at all, that Mr. Leslie did?” asked another; “I didn’t hear how it begun yet.”

“Nor I either, rightly; but I believe Mary was standing looking at the dance, for she never foots a step herself—maybe she’s too ginteel—and the young gentleman comes up and axes her for a partner; and something she said; but what does he do, but put his arm round her waist and gives her a kiss; and, ye see, the other girls laughed hearty, because they say, Mary’s so proud and high, and thinking herself above them all. Phil wasn’t there at the time; but he heerd it afterwards, and come up to the tent, as young Mr. Leslie was laving it, and stood before him and wouldn’t let him pass. ‘I’ve a word to say to ye,’ says Phil, and he scarce able to spake with passion; ‘that was my sister ye had the impudence to take a liberty with.’ ‘Out of the way, ye bogtrotter,’ says Leslie: them’s the very words he said; ‘out of the way, ye bog-trotter, or I’ll lay my whip across your shoulders.’ ‘Take that first,’ says Phil; and he put his fist between his two eyes, neat and clean;—down went the Squire as if he was shot. You know the rest yourselves. The boys didn’t lose any time, and if ‘twas only two hours later, maybe the Joyces would have got as good as they gave.”

A heavy groan from poor Owen now stopped the conversation, and they halted to ascertain if he were worse,—but no; he seemed still sunk in the same heavy sleep as before, and apparently unconscious of all about him. Such, however, was not really the case; by some strange phenomenon of sickness, the ear had taken in each low and whispered word, at the time it would have been deaf to louder sounds; and every syllable they had spoken had already sunk deeply into his heart; happily for him, this was hut a momentary pang; the grief stunned him at once, and he became insensible.

It was dark night as they reached the lonely cabin where Owen lived, miles away from any other dwelling, and standing at an elevation of more than a thousand feet above the plain. The short, sharp barking of a sheep-dog was the only sound that welcomed them; for the old man had not heard of his son’s misfortune until long after they quitted the fair. The door was hasped and fastened with a stick; precaution enough in such a place, and for all that it contained, too. Opening this, they carried the young man in, and laid him upon the bed; and, while some busied themselves in kindling a fire upon the hearth, the others endeavoured, with such skill as they possessed, to dress his wounds, an operation which, if not strictly surgical in all its details, had at least the recommendation of tolerable experience in such matters.

“It’s a nate little place when you’re at it, then,” said one of them, as with a piece of lighted bog-pine he took a very leisurely and accurate view of the interior.

The opinion, however, must be taken by the reader, as rather reflecting on the judgment of him who pronounced it, than in absolute praise of the object itself. The cabin consisted of a single room, and which, though remarkably clean in comparison with similar ones, had no evidence of anything above very narrow circumstances. A little dresser occupied the wall in front of the door, with its usual complement of crockery, cracked and whole; an old chest of drawers, the pride of the house, flanked this on one side; a low settle-bed on the other; various prints in very florid colouring decorated the walls, all religious subjects, where the Apostles figured in garments like bathing-dresses; these were intermixed with ballads, dying speeches, and suchlike ghostly literature, as form the most interesting reading of an Irish peasant; a few seats of unpainted deal, and a large straw chair for the old man, were the principal articles of furniture. There was a gun, minus the lock, suspended over the fireplace; and two fishing-rods, with a gaff and landing-net, were stretched upon wooden pegs; while over the bed was an earthenware crucifix, with its little cup beneath, for holy water; the whole surmounted by a picture of St. Francis Xavier in the act of blessing somebody: though, if the gesture were to be understood without the explanatory letter-press, he rather looked like a swimmer preparing for a dive. The oars, mast, and spritsail of a boat were lashed to the rafters overhead; for, strange as it may seem, there was a lake at that elevation of the mountain, and one which abounded in trout and perch, affording many a day’s sport to both Owen and his father.

Such were the details which, sheltered beneath a warm roof of mountain-fern, called forth the praise we have mentioned; and, poor as they may seem to the reader, they were many degrees in comfort beyond the majority of Irish cabins.

The boys—for so the unmarried men of whatever age are called—having left one of the party to watch over Owen, now quitted the house, and began their return homeward. It was past midnight when the old man returned; and although endeavouring to master any appearance of emotion before the “strange boy,” he could with difficulty control his feelings on beholding his son. The shirt matted with blood, contrasting with the livid colourless cheek—the heavy irregular breathing—the frequent startings as he slept—were all sore trials to the old man’s nerve; but he managed to seem calm and collected, and to treat the occurrence as an ordinary one.

“Harry Joyce and his brother Luke—big Luke as they call him—has sore bones to-night; they tell me that Owen didn’t lave breath in their bodies,” said he, with a grim smile, as he took his place by the fire.

“I heerd the ribs of them smashing like an ould turf creel,” replied the other.

“‘Tis himself can do it,” said the old fellow, with eyes glistening with delight; “fair play and good ground, and I’d back him agin the Glen.”

“And so you might, and farther too; he has the speret in him—that’s better nor strength, any day.”

And thus consoled by the recollection of Owen’s prowess, and gratified by the hearty concurrence of his guest, the old father smoked and chatted away till daybreak. It was not that he felt any want of affection for his son, or that his heart was untouched by the sad spectacle he presented,—far from this; the poor old man had no other tie to life—no other object of hope or love than Owen; but years of a solitary life had taught him rather to conceal his emotions within his own bosom, than seek for consolation beyond it; besides that, even in his grief the old sentiment of faction-hatred was strong, and vengeance had its share in his thoughts also.

It would form no part of our object in this story, to dwell longer either on this theme, or the subject of Owen’s illness; it will be enough to say, that he soon got better, far sooner perhaps than if all the appliances of luxury had ministered to his recovery; most certainly sooner than if his brain had been ordinarily occupied by thoughts and cares of a higher order than his were. The conflict, however, had left a deeper scar behind, than the ghastly wound that marked his brow. The poor fellow dwelt upon the portions of the conversation he overheard as they carried him up the mountain; and whatever might have been his fears before, now he was convinced that all prospect of gaining Mary’s love was lost to him for ever.

This depression, natural to one after so severe an injury, excited little remark from the old man; and although he wished Owen might make some effort to exert himself, or even move about in the air, he left him to himself and his own time, well knowing that he never was disposed to yield an hour to sickness, beyond what he felt unavoidable.

It was about eight or nine days after the fair, that the father was sitting mending a fishing-net at the door of his cabin, to catch the last light of the fading day. Owen was seated near him, sometimes watching the progress of the work, sometimes patting the old sheep-dog that nestled close by, when the sound of voices attracted them: they listened, and could distinctly hear persons talking at the opposite side of the cliff, along which the pathway led; and before they could even hazard a guess as to who they were, the strangers appeared at the angle of the rock. The party consisted of two persons; one, a gentleman somewhat advanced in life, mounted on a stout but rough-looking pony—the other, was a countryman, who held the beast by the bridle, and seemed to take the greatest precaution for the rider’s safety.

The very few visitors Owen and his father met with were for the most part people coming to fish the mountain-lake, who usually hired ponies in the valley for the ascent; so that when they perceived the animal coming slowly along, they scarce bestowed a second glance upon them, the old man merely remarking, “They’re three weeks too early for this water, any how;” a sentiment concurred in by his son. In less than five minutes after, the rider and his guide stood before the door.

“Is this where Owen Connor lives?” asked the gentleman.

“That same, yer honor,” said old Owen, uncovering his head, as he rose respectfully from his low stool.

“And where is Owen Connor himself?”

“‘Tis me, sir,” replied he; “that’s my name.”

“Yes, but it can scarcely be you that I am looking for; have you a son of that name?”

“Yes, sir, I’m young Owen,” said the young man, rising, but not without difficulty; while he steadied himself by holding the door-post.

“So then I am all right: Tracy, lead the pony about, till I call you;” and so saying, he dismounted and entered the cabin.

“Sit down, Owen; yes, yes—I insist upon it, and do you, also. I have come up here to-day to have a few moments’ talk with you about an occurrence that took place last week at the fair. There was a young gentleman, Mr. Leslie, got roughly treated by some of the people: let me hear your account of it.”

Owen and his father exchanged glances; the same idea flashed across the minds of both, that the visitor was a magistrate come to take information against the Joyces for an assault; and however gladly they would have embraced any course that promised retaliation for their injuries, the notion of recurring to the law was a degree of baseness they would have scorned to adopt.

“I’ll take the ‘vestment’ I never seen it at all,” said the old man eagerly, and evidently delighted that no manner of cross-questioning or badgering could convert him into an informer.

“And the little I saw,” said Owen, “they knocked out of my memory with this;” and he pointed to the half-healed gash on his forehead.

“But you know something of how the row begun?”

“No, yer honor, I was at the other side of the fair.”

“Was young Mr. Leslie in fault—did you hear that?”

“I never heerd that he did any thing—unagreeable,” said Owen, after hesitating for a few seconds in his choice of a word.

“So then, I’m not likely to obtain any information from either of you.”

They made no reply, but their looks gave as palpable a concurrence to this speech, as though they swore to its truth.

“Well, I have another question to ask. It was you saved this young gentleman, I understand; what was your motive for doing so? when, as by your own confession, you were at a distance when the fight begun.”

“He was my landlord’s son,” said Owen, half roughly; “I hope there is no law agin that.”

“I sincerely trust not,” ejaculated the gentleman; “have you been long on the estate?”

“Three generations of us now, yer honor,” said the old man.

“And what rent do you pay?”

“Oh, musha, we pay enough! we pay fifteen shillings an acre for the bit of callows below, near the lake, and we give ten pounds a year for the mountain—and bad luck to it for a mountain—it’s breaking my heart, trying to make something out of it.”

“Then I suppose you’d be well pleased to exchange your farm, and take one in a better and more profitable part of the country?”

Another suspicion here shot across the old man’s mind; and turning to Owen he said in Irish: “He wants to get the mountain for sporting over; but I’ll not lave it.”

The gentleman repeated his question.

“Troth, no then, yer honor; we’ve lived here so long we’ll just stay our time in it.”

“But the rent is heavy, you say.”

“Well, we’ll pay it, plaze God.”

“And I’m sure it’s a strange wild place in winter.”

“Its wholesome, any how,” was the short reply.

“I believe I must go back again as wise as I came,” muttered the gentleman. “Come, my good old man,—and you, Owen; I want to know how I can best serve you, for what you’ve done for me: it was my son you rescued in the fair—”

“Are you the landlord—is yer honor Mr. Leslie?” exclaimed both as they rose from their seats, as horrified as if they had taken such a liberty before Royalty.

“Yes, Owen; and I grieve to say, that I should cause so much surprise to any tenant, at seeing me. I ought to be better known on my property; and I hope to become so: but it grows late, and I must reach the valley before night. Tell me, are you really attached to this farm, or have I any other, out of lease at this time, you like better?”

“I would not leave the ould spot, with yer honor’s permission, to get a demesne and a brick house; nor Owen neither.”

“Well, then, be it so; I can only say, if you ever change your mind, you’ll find me both ready and willing to serve you; meanwhile you must pay no more rent, here.”

“No more rent!”

“Not a farthing; I’m sorry the favour is so slight a one, for indeed the mountain seems a bleak and profitless tract.”

“There is not its equal for mutton—”

“I’m glad of it, Owen; and it only remains for me to make the shepherd something more comfortable;—well, take this; and when I next come up here, which I intend to do, to fish the lake, I hope to find you in a better house;” and he pressed a pocket-book into the old man’s hand as he said this, and left the cabin: while both Owen and his father were barely able to mutter a blessing upon him, so overwhelming and unexpected was the whole occurrence.

From no man’s life, perhaps, is hope more rigidly excluded than from that of the Irish peasant of a poor district. The shipwrecked mariner upon his raft, the convict in his cell, the lingering sufferer on a sick hed, may hope; but he must not.

Daily labour, barely sufficient to produce the commonest necessaries of life, points to no period of rest or repose; year succeeds year in the same dull routine of toil and privation; nor can he look around him and see one who has risen from that life of misery, to a position of even comparative comfort.

The whole study of his existence, the whole philosophy of his life, is, how to endure; to struggle on under poverty and sickness; in seasons of famine, in times of national calamity, to hoard up the little pittance for his landlord and the payment for his Priest; and he has nothing more to seek for. Were it our object here, it would not be difficult to pursue this theme further, and examine, if much of the imputed slothfulness and indolence of the people was not in reality due to that very hopelessness. How little energy would be left to life, if you took away its ambitions; how few would enter upon the race, if there were no goal before them! Our present aim, however, is rather with the fortunes of those we have so lately left. To these poor men, now, a new existence opened. Not the sun of spring could more suddenly illumine the landscape where winter so late had thrown its shadows, than did prosperity fall brightly on their hearts, endowing life with pleasures and enjoyments, of which they had not dared to dream before.

In preferring this mountain-tract to some rich lowland farm, they were rather guided by that spirit of attachment to the home of their fathers—so characteristic a trait in the Irish peasant—than by the promptings of self-interest. The mountain was indeed a wild and bleak expanse, scarce affording herbage for a few sheep and goats; the callows at its foot, deeply flooded in winter, and even by the rains of autumn, made tillage precarious and uncertain; yet the fact that these were rent-free, that of its labour and its fruits all was now their own, inspired hope and sweetened toil. They no longer felt the dreary monotony of daily exertion, by which hour was linked to hour, and year to year, in one unbroken succession;—no; they now could look forward, they could lift up their hearts and strain their eyes to a future, where honest industry had laid up its store for the decline of life; they could already fancy the enjoyments of the summer season, when they should look down upon their own crops and herds, or think of the winter nights, and the howling of the storm without, reminding them of the blessings of a home.

How little to the mind teeming with its bright and ambitious aspirings would seem the history of their humble hopes! how insignificant and how narrow might appear the little plans and plots they laid for that new road in life, in which they were now to travel! The great man might scoff at these, the moralist might frown at their worldliness; but there is nothing sordid or mean in the spirit of manly independence; and they who know the Irish people, will never accuse them of receiving worldly benefits with any forgetfulness of their true and only source. And now to our story.

The little cabin upon the mountain was speedily added to, and fashioned into a comfortable-looking farmhouse of the humbler class. Both father and son would willingly have left it as it was; but the landlord’s wish had laid a command upon them, and they felt it would have been a misapplication of his bounty, had they not done as he had desired. So closely, indeed, did they adhere to his injunctions, that a little room was added specially for his use and accommodation, whenever he came on that promised excursion he hinted at. Every detail of this little chamber interested them deeply; and many a night, as they sat over their fire, did they eagerly discuss the habits and tastes of the “quality,” anxious to be wanting in nothing which should make it suitable for one like him.

Sufficient money remained above all this expenditure to purchase some sheep, and even a cow; and already their changed fortunes had excited the interest and curiosity of the little world in which they lived.

There is one blessing, and it is a great one, attendant on humble life. The amelioration of condition requires not that a man should leave the friends and companions he has so long sojourned with, and seek, in a new order, others to supply their place; the spirit of class does not descend to him, or rather, he is far above it; his altered state suggests comparatively few enjoyments or comforts in which his old associates cannot participate; and thus the Connors’ cabin was each Sunday thronged by the country people, who came to see with their own eyes, and hear with their own ears, the wonderful good fortune that befell them.

Had the landlord been an angel of light, the blessings invoked upon him could not have been more frequent or fervent; each measured the munificence of the act by his own short standard of worldly possessions; and individual murmurings for real or fancied wrongs were hushed in the presence of one such deed of benevolence.

This is no exaggerated picture. Such was peasant-gratitude once; and such, O landlords of Ireland! it might still have been, if you had not deserted the people. The meanest of your favours, the poorest show of your good-feeling, were acts of grace for which nothing was deemed requital. Your presence in the poor man’s cabin—your kind word to him upon the highway—your aid in sickness—your counsel in trouble, were ties which bound him more closely to your interest, and made him more surely yours, than all the parchments of your attorney, or all the papers of your agent. He knew you then as something more than the recipient of his earnings. That was a time, when neither the hireling patriot nor the calumnious press could sow discord between you. If it be otherwise now, ask yourselves, are you all blameless? Did you ever hope that affection could be transmitted through your agent, like the proceeds of your property? Did you expect that the attachments of a people were to reach you by the post? Or was it not natural, that, in their desertion by you, they should seek succour elsewhere? that in their difficulties and their trials they should turn to any who might feel or feign compassion for them?

Nor is it wonderful that, amid the benefits thus bestowed, they should imbibe principles and opinions fatally in contrast with interests like yours.

There were few on whom good fortune could have fallen, without exciting more envious and jealous feelings on the part of others, than on the Connors. The rugged independent character of the father—the gay light-hearted nature of the son, had given them few enemies and many friends. The whole neighbourhood flocked about them to offer their good wishes and congratulations on their bettered condition, and with an honesty of purpose and a sincerity that might have shamed a more elevated sphere. The Joyces alone shewed no participation in this sentiment, or rather, that small fraction of them more immediately linked with Phil Joyce. At first, they affected to sneer at the stories of the Connors’ good fortune; and when denial became absurd, they half-hinted that it was a new custom in Ireland for men “to fight for money.” These mocking speeches were not slow to reach the ears of the old man and his son; and many thought that the next fair-day would bring with it a heavy retribution for the calamities of the last. In this, however, they were mistaken. Neither Owen nor his father appeared that day; the mustering of their faction was strong and powerful, but they, whose wrongs were the cause of the gathering, never came forward to head them.

This was an indignity not to be passed over in silence; and the murmurs, at first low and subdued, grew louder and louder, until denunciations heavy and deep fell upon the two who “wouldn’t come out and right themselves like men.” The faction, discomfited and angered, soon broke up; and returning homeward in their several directions, they left the field to the enemy without even a blow. On the succeeding day, when the observances of religion had taken place of the riotous and disorderly proceedings of the fair, it was not customary for the younger men to remain. The frequenters of the place were mostly women; the few of the other sex were either old and feeble men, or such objects of compassion as traded on the pious feelings of the votaries so opportunely evoked. It was with great difficulty the worthy Priest of the parish had succeeded in dividing the secular from the holy customs of the time, and thus allowing the pilgrims, as all were called on that day, an uninterrupted period for their devotions. He was firm and resolute, however, in his purpose, and spared no pains to effect it: menacing this one—persuading that; suiting the measure of his arguments to the comprehension of each, he either cajoled or coerced, as the circumstance might warrant. His first care was to remove all the temptations to dissipation and excess; and for this purpose, he banished every show and exhibition, and every tent where gambling and drinking went forward;—his next, a more difficult task, was the exclusion of all those doubtful characters, who, in every walk of life, are suggestive of even more vice than they embody in themselves. These, however, abandoned the place, of their own accord, so soon as they discovered how few were the inducements to remain; until at length, by a tacit understanding, it seemed arranged, that the day of penance and mortification should suffer neither molestation nor interruption from those indisposed to partake of its benefits. So rigid was the Priest in exacting compliance in this matter, that he compelled the tents to be struck by daybreak, except by those few, trusted and privileged individuals, whose ministerings to human wants were permitted during the day of sanctity.

And thus the whole picture was suddenly changed. The wild and riotous uproar of the fair, the tumult of voices and music, dancing, drinking, and fighting, were gone; and the low monotonous sound of the pilgrims’ prayers was heard, as they moved along upon their knees to some holy well or shrine, to offer up a prayer, or return a thanksgiving for blessings bestowed. The scene was a strange and picturesque one; the long lines of kneeling figures, where the rich scarlet cloak of the women predominated, crossed and recrossed each other as they wended their way to the destined altar; their muttered words blending with the louder and more boisterous appeals of the mendicants,—who, stationed at every convenient angle or turning, besieged each devotee with unremitting entreaty,—deep and heartfelt devotion in every face, every lineament and feature impressed with religious zeal and piety; but still, as group met group going and returning, they interchanged their greetings between their prayers, and mingled the worldly salutations with aspirations heavenward, and their “Paters,” and “Aves,” and “Credos,” were blended with inquiries for the “childer,” or questions about the “crops.”

“Isn’t that Owen Connor, avick, that’s going there, towards the Yallow-well?” said an old crone as she ceased to count her beads.

“You’re right enough, Biddy; ‘tis himself, and no other; it’s a turn he took to devotion since he grew rich.”

“Ayeh! ayeh! the Lord be good to us! how fond we all be of life, when we’ve the bit of bacon to the fore!” And with that she resumed her pious avocations with redoubled energy, to make up for lost time.

The old ladies were as sharp-sighted as such functionaries usually are in any sphere of society. It was Owen Connor himself, performing his first pilgrimage. The commands of his landlord had expressly forbidden him to engage in any disturbance at the fair; the only mode of complying with which, he rightly judged, was by absenting himself altogether. How this conduct was construed by others, we have briefly hinted at. As for himself, poor fellow, if a day of mortification could have availed him any thing, he needn’t have appeared among the pilgrims;—a period of such sorrow and suffering he had never undergone before. But in justice it must be confessed, it was devotion of a very questionable character that brought him there that morning. Since the fair-day, Mary Joyce had never deigned to notice him; and though he had been several times at mass, she either affected not to be aware of his presence, or designedly looked in another direction. The few words of greeting she once gave him on every Sunday morning—the smile she bestowed—dwelt the whole week in his heart, and made him long for the return of the time, when, even for a second or two, she would be near, and speak to him. He was not slow in supposing how the circumstances under which he rescued the landlord’s son might be used against him by his enemies; and he well knew that she was not surrounded by any others than such. It was, then, with a heavy heart poor Owen witnessed how fatally his improved fortune had dashed hopes far dearer than all worldly advantage. Not only did the new comforts about him become distasteful, but he even accused them to himself as the source of all his present calamity; and half suspected that it was a judgment on him for receiving a reward in such a cause. To see her—to speak to her if possible—was now his wish, morn and night; to tell her that he cared more for one look, one glance, than for all the favours fortune did or could bestow: this, and to undeceive her as to any knowledge of young Leslie’s rudeness to herself, was the sole aim of his thoughts. Stationing himself therefore in an angle of the ruined church, which formed one of the resting-places for prayer, he waited for hours for Mary’s coming; and at last, with a heart half sickened with deferred hope, he saw her pale but beautiful features, shaded by the large blue hood of her cloak, as with downcast eyes she followed in the train.

“Give me your place, acushla; God will reward you for it; I’m late at the station,” said he, to an old ill-favoured hag that followed next to Mary; and at the same time, to aid his request, slipped half-a-crown into her hand.

The wrinkled face brightened into a kind of wicked intelligence as she muttered in Irish: “‘Tis a gould guinea the same place is worth; but I’ll give it to you for the sake of yer people;” and at the same time pocketing the coin in a canvass pouch, among relics and holy clay, she moved off, to admit him in the line.

Owen’s heart beat almost to bursting, as he found himself so close to Mary; and all his former impatience to justify himself, and to speak to her, fled in the happiness he now enjoyed. No devotee ever regarded the relic of a Saint with more trembling ecstacy than did he the folds of that heavy mantle that fell at his knees; he touched it as men would do a sacred thing. The live-long day he followed her, visiting in turn each shrine and holy spot; and ever, as he was ready to speak to her, some fear that, by a word, he might dispel the dream of bliss he revelled in, stopped him, and he was silent.

It was as the evening drew near, and the Pilgrims were turning towards the lake, beside which, at a small thorn-tree, the last “station” of all was performed, that an old beggar, whose importunity suffered none to escape, blocked up the path, and prevented Mary from proceeding until she had given him something. All her money had been long since bestowed; and she said so, hurriedly, and endeavoured to move forward.

“Let Owen Connor, behyind you, give it, acushla! He’s rich now, and can well afford it,” said the cripple.

She turned around at the words; the action was involuntary, and their eyes met. There are glances which reveal the whole secret of a lifetime; there are looks which dwell in the heart longer and deeper than words. Their eyes met for merely a few seconds; and while in her face offended pride was depicted, poor Owen’s sorrow-struck and broken aspect spoke of long suffering and grief so powerfully, that, ere she turned away, her heart had half forgiven him.

“You wrong me hardly, Mary,” said he, in a low, broken voice, as the train moved on. “The Lord, he knows my heart this blessed day! Pater noster, qui es in colis?’” added he, louder, as he perceived that his immediate follower had ceased his prayers to listen to him. “He knows that I’d rather live and die the poorest—‘Beneficat tuum nomen!’” cried he, louder. And then, turning abruptly, said:

“Av it’s plazing to you, sir, don’t be trampin’ on my heels. I can’t mind my devotions, an’ one so near me.

“It’s not so unconvaynient, maybe, when they’re afore you,” muttered the old fellow, with a grin of sly malice. And though Owen overheard the taunt, he felt no inclination to notice it.

“Four long years I’ve loved ye, Mary Joyce; and the sorra more encouragement I ever got nor the smile ye used to give me. And if ye take that from me, now—Are ye listening to me, Mary? do ye hear me, asthore?—Bad scran to ye, ye ould varmint! why won’t ye keep behind? How is a man to save his sowl, an’ you making him blasphame every minit?”

“I was only listenin’ to that elegant prayer ye were saying,” said the old fellow, drily.

“‘Tis betther you’d mind your own, then,” said Owen, fiercely; “or, by the blessed day, I’ll teach ye a new penance ye never heerd of afore!”

The man dropped back, frightened at the sudden determination these words were uttered in; and Owen resumed his place.

“I may never see ye again, Mary. ‘Tis the last time you’ll hear me spake to you. I’ll lave the ould man. God look to him! I’ll lave him now, and go be a sodger. Here we are now, coming to this holy well; and I’ll swear an oath before the Queen of Heaven, that before this time to-morrow—”

“How is one to mind their prayers at all, Owen Connor, if ye be talking to yourself, so loud?” said Mary, in a whisper, but one which lost not a syllable, as it fell on Owen’s heart.

“My own sweet darling, the light of my eyes, ye are!” cried he, as with clasped hands he muttered blessings upon her head; and with such vehemence of gesture, and such unfeigned signs of rapture, as to evoke remarks from some beggars near, highly laudatory of his zeal.

“Look at the fine young man there, prayin’ wid all his might. Ayeh, the Saints give ye the benefit of your Pilgrimage!”

“Musha! but ye’r a credit to the station; ye put yer sowl in it, anyhow!” said an old Jezebel, whose hard features seemed to defy emotion.

Owen looked up; and directly in front of him, with his back against a tree, and his arms crossed on his breast, stood Phil Joyce: his brow was dark with passion, and his eyes glared like those of a maniac. A cold thrill ran through Owen’s heart, lest the anger thus displayed should fall on Mary; for he well knew with what tyranny the poor girl was treated. He therefore took the moment of the pilgrims’ approach to the holy tree, to move from his place, and, by a slightly circuitous path, came up to where Joyce was standing.

“I’ve a word for you, Phil Joyce,” said he, in a low voice, where every trace of emotion was carefully subdued. “Can I spake it to you here?”

Owen’s wan and sickly aspect, if it did not shock, it at least astonished Joyce, for he looked at him for some seconds without speaking; then said, half rudely:

“Ay, here will do as well as any where, since ye didn’t like to say it yesterday.”

There was no mistaking this taunt; the sneer on Owen’s want of courage was too plain to be misconstrued; and although for a moment he looked as if disposed to resent it, he merely shook his head mournfully, and replied: “It is not about that I came to speak; it’s about your sister, Mary Joyce.”

Phil turned upon him a stare of amazement, as quickly followed by a laugh, whose insulting mockery made Owen’s cheek crimson with shame.

“True enough, Phil Joyce; I know your meanin’ well,” said he, with an immense effort to subdue his passion. “I’m a poor cottier, wid a bit of mountain-land—sorra more—and has no right to look up to one like her. But listen to me, Phil!” and here he grasped his arm, and spoke with a thick guttural accent: “Listen to me! Av the girl wasn’t what she is, but only your sister, I’d scorn her as I do yourself;” and with that, he pushed him from him with a force that made him stagger. Before he had well recovered, Owen was again at his side, and continued:—“And now, one word more, and all’s ended between us. For you, and your likings or mis-likings, I never cared a rush: but ‘tis Mary herself refused me, so there’s no more about it; only don’t be wreaking your temper on her, for she has no fault in it.”

“Av a sister of mine ever bestowed a thought on the likes o’ ye, I’d give her the outside of the door this night,” said Joyce, whose courage now rose from seeing several of his faction attracted to the spot, by observing that he and Connor were conversing. “‘Tis a disgrace—divil a less than a disgrace to spake of it!”

“Well, we won’t do so any more, plaze God!” said Owen, with a smile of very fearful meaning. “It will be another little matter we’ll have to settle when we meet, next. There’s a score there, not paid off yet:” and at the word he lifted his hat, and disclosed the deep mark of the scarce-closed gash on his forehead: “and so, good bye to ye.”

A rude nod from Phil Joyce was all the reply, and Owen turned homewards.

If prosperity could suggest the frame of mind to enjoy it, the rich would always be happy; but such is not the dispensation of Providence. Acquisition is but a stage on the road of ambition; it lightens the way, but brings the goal no nearer. Owen never returned to his mountain-home with a sadder heart. He passed without regarding them, the little fields, now green with the coming spring; he bestowed no look nor thought upon the herds that already speckled the mountain-side; disappointment had embittered his spirit; and even love itself now gave way to faction-hate, the old and cherished animosity of party.

If the war of rival factions did not originally spring from the personal quarrels of men of rank and station, who stimulated their followers and adherents to acts of aggression and reprisal, it assuredly was perpetuated, if not with their concurrence, at least permission; and many were not ashamed to avow, that in these savage encounters the “bad blood” of the country was “let out,” at less cost and trouble than by any other means. When legal proceedings were recurred to, the landlord, in his capacity of magistrate, maintained the cause of his tenants; and, however disposed to lean heavily on them himself, in the true spirit of tyranny he opposed pressure from any other hand than his own. The people were grateful for this advocacy—far more, indeed, than they often proved for less questionable kindness. They regarded the law with so much dread—they awaited its decisions with such uncertainty—that he who would conduct them through its mazes was indeed a friend. But, was the administration of justice, some forty or fifty years back in Ireland, such as to excite or justify other sentiments? Was it not this tampering with right and wrong, this recurrence to patronage, that made legal redress seem an act of meanness and cowardice among the people? No cause was decided upon its own merits. The influence of the great man—the interest he was disposed to take in the case—the momentary condition of county politics—with the general character of the individuals at issue, usually determined the matter; and it could scarcely be expected that a triumph thus obtained should have exercised any peaceful sway among the people.

“He wouldn’t be so bould to-day, av his landlord wasn’t to the fore,” was Owen Connor’s oft-repeated reflection, as he ascended the narrow pathway towards his cabin; “‘tis the good backing makes us brave, God help us!” From that hour forward, the gay light-hearted peasant became dark, moody, and depressed; the very circumstances which might be supposed calculated to have suggested a happier frame of mind, only increased and embittered his gloom. His prosperity made daily labour no longer a necessity. Industry, it is true, would have brought more comforts about him, and surrounded him with more appliances of enjoyment; but long habits of endurance had made him easily satisfied on this score, and there were no examples for his imitation which should make him strive for better. So far, then, from the landlord’s benevolence working for good, its operation was directly the reverse; his leniency had indeed taken away the hardship of a difficult and onerous payment, but the relief suggested no desire for an equivalent amelioration of condition. The first pleasurable emotions of gratitude over, they soon recurred to the old customs in every thing, and gradually fell hack into all the observances of their former state, the only difference being, that less exertion on their parts was now called for than before.

Had the landlord been a resident on his property—acquainting himself daily and hourly with the condition of his tenants—holding up examples for their imitation—rewarding the deserving—discountenancing the unworthy—extending the benefits of education among the young—and fostering habits of order and good conduct among all, Owen would have striven among the first for a place of credit and honour, and speedily have distinguished himself above his equals. But alas! no; Mr. Leslie, when not abroad, lived in England. Of his Irish estates he knew nothing, save through the half-yearly accounts of his agent. He was conscious of excellent intentions; he was a kind, even a benevolent man; and in the society of his set, remarkable for more than ordinary sympathies with the poor. To have ventured on any reflection on a landlord before him, would have been deemed a downright absurdity.

He was a living refutation of all such calumnies; yet how was it, that, in the district he owned, the misery of the people was a thing to shudder at? that there were hovels excavated in the bogs, within which human beings lingered on between life and death, their existence like some terrible passage in a dream? that beneath these frail roofs famine and fever dwelt, until suffering, and starvation itself, had ceased to prey upon minds on which no ray of hope ever shone? Simply he did not know of these things; he saw them not; he never heard of them. He was aware that seasons of unusual distress occurred, and that a more than ordinary degree of want was experienced by a failure of the potato-crop; but on these occasions, he read his name, with a subscription of a hundred pounds annexed, and was not that a receipt in full for all the claims of conscience? He ran his eyes over a list in which Royal and Princely titles figured, and he expressed himself grateful for so much sympathy with Ireland! But did he ask himself the question, whether, if he had resided among his people, such necessities for alms-giving had ever arisen? Did he inquire how far his own desertion of his tenantry—his ignorance of their state—his indifference to their condition—had fostered these growing evils? Could he acquit himself of the guilt of deriving all the appliances of his ease and enjoyment, from those whose struggles to supply them were made under the pressure of disease and hunger? Was unconsciousness of all this, an excuse sufficient to stifle remorse? Oh, it is not the monied wealth dispensed by the resident great man; it is not the stream of affluence, flowing in its thousand tiny rills, and fertilising as it goes, we want. It is far more the kindly influence of those virtues which. And their congenial soil in easy circumstances; benevolence, sympathy, succour in sickness, friendly counsel in distress, timely aid in trouble, encouragement to the faint-hearted, caution to the over-eager: these are gifts, which, giving, makes the bestower richer; and these are the benefits which, better than gold, foster the charities of life among a people, and bind up the human family in a holy and indissoluble league. No benevolence from afar, no well wishings from distant lands, compensate for the want of them. To neglect such duties is to fail in the great social compact by which the rich and poor are united, and, what some may deem of more moment still, to resign the rightful influence of property into the hands of dangerous and designing men.

It is in vain to suppose that traditionary deservings will elicit gratitude when the present generation are neglectful. On the contrary, the comparison of the once resident, now absent landlord, excites very different feelings; the murmurings of discontent swell into the louder language of menace; and evils, over which no protective power of human origin could avail, are ascribed to that class, who, forgetful of one great duty, are now accused of causing every calamity. If not present to exercise the duties their position demands, their absence exaggerates every accusation against them; and from the very men, too, who have, by the fact of their desertion, succeeded in obtaining the influence that should be theirs.