Project Gutenberg's The Daltons, Volume I (of II), by Charles James Lever

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

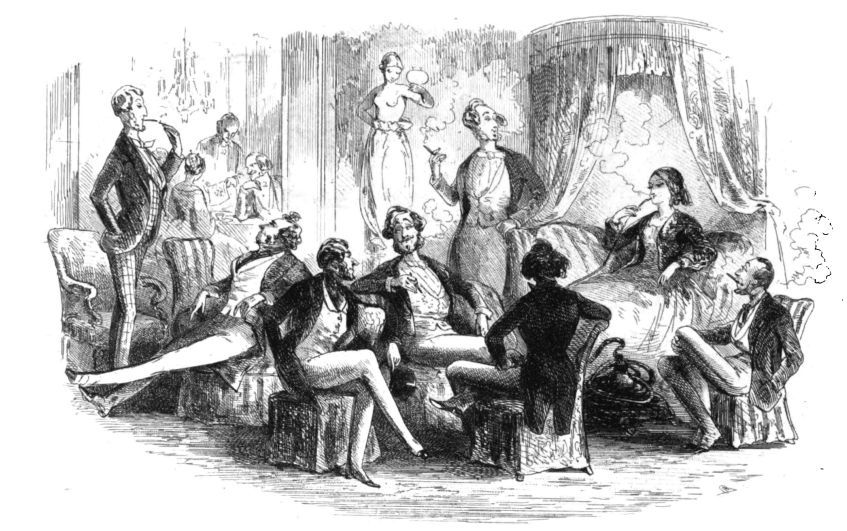

Title: The Daltons, Volume I (of II)

Or,Three Roads In Life

Author: Charles James Lever

Illustrator: Phiz.

Release Date: April 19, 2010 [EBook #32061]

Last Updated: September 2, 2016

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE DALTONS, VOLUME I (OF II) ***

Produced by David Widger

To LORD METHUEN.

MY DEAR METHUEN, Some idle folk have pretended that certain living characters have been depicted under the fictitious names of these volumes. There is, I assure you, but one personality contained in it, and that is of a right true-hearted Englishman, hospitable, and manly in all his dealings; and to him I wish to dedicate my book, in testimony not only of the gratitude which, in common with all his countrymen here, I feel to be his due, but in recognition of many happy hours passed in his society, and the honor of his friendship. The personality begins and ends with this dedication, which I beg you to accept of, and am

Ever yours faithfully,

CHARLES LEVER.

PALAZZO CAPPONI, FLORENCE, Feb. 28, 1852.

CONTENTS

PREFACE.

THE DALTONS, OR THREE ROADS IN LIFE

CHAPTER I. BADEN OUT OF SEASON

CHAPTER II. AN HUMBLE INTERIOR

CHAPTER III. THE FOREST ROAD

CHAPTER IV. THE ONSLOWS

CHAPTER V. THE PATIENT

CHAPTER VI. A FIRST VISIT

CHAPTER VII. A LESSON IN PISTOL-SHOOTING

CHAPTER VIII. THE NIGHT EXCURSION

CHAPTER IX. A FINE LADY’S BLANDISHMENTS

CHAPTER X. A FAMILY DISCUSSION

CHAPTER XI. A PEEP BETWEEN THE SHUTTERS AT A NEW CHARACTER

CHAPTER XII. MR. ALBERT JEKYL

CHAPTER XIII. A SUSPICIOUS VISITOR

CHAPTER XIV. AN EMBARRASSING QUESTION

CHAPTER XV. CONTRASTS

CHAPTER XVI. THE “SAAL” OF THE “RUSSIE.”

CHAPTER XVII. A FAMILY DISCUSSION

CHAPTER XVIII. CARES AND CROSSES

CHAPTER XIX. PREPARATIONS FOR THE ROAD

CHAPTER XX. A VERY SMALL “INTERIOR.”

CHAPTER XXI. A FAMILY PICTURE

CHAPTER XXII. KATE

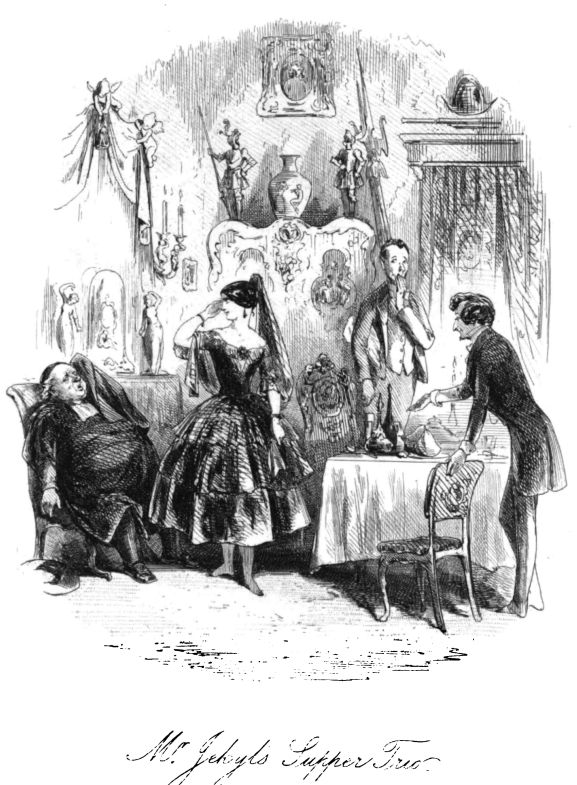

CHAPTER XXIII. A SMALL SUPPER PARTY

CHAPTER XXIV. A MIDNIGHT RECEPTION

CHAPTER XXV. A “LEVANTER.”

CHAPTER XXVI. THE END OF THE FIRST ACT

CHAPTER XXVII. A SMALL DINNER AT THE VILLINO ZOE

CHAPTER XXVIII. THE VISCOUNT’S VISION

CHAPTER XXIX. FRANK’S JOURNEY

CHAPTER XXX. THE THREAT OF “A SLIGHT EMBARRASSMENT.”

CHAPTER XXXI. A CONVIVIAL EVENING

CHAPTER XXXII. AN INVASION

CHAPTER XXXIII. THE CONCLUSION OF A “GRAND DINNER.”

CHAPTER XXXIV. JEKYL’S COUNSELS

CHAPTER XXXV. RACCA MORLACHE

CHAPTER XXXVI. A STREET RENCONTRE

CHAPTER XXXVII. PROPOSALS

CHAPTER XXXVIII. AN ARRIVAL

CHAPTER XXXIX. PRATOLINO

IF the original conception of this tale was owing to the story of an old and valued schoolfellow who took service in Austria, and rose to rank and honors there, all the rest was purely fictitious. My friend had made a deep impression on my mind by his narratives of that strange life, wherein, in the very midst of our modern civilization, an old-world tradition still has its influence, making the army of to-day the veritable sons and descendants of those who grouped around the bivouac fires in Wallenstein’s camp. Of that more than Oriental submission that graduated deference to military rank that chivalrous devotion to the “Kaiser” whicli enter into the soldier heart of Austria, I have been unable to reproduce any but the very faintest outlines, and yet these were the traits which, pervaded all my friend’s stories and gave them character and distinctiveness.

Many of the other characters in this tale were drawn from the life, with such changes added and omitted features as might rescue them from any charge of personality. With all my care on this score, one or two have been believed to be recognizable; and if so I have only to hope that I have touched on peculiarities of disposition inoffensively, and only depicted such traits as may “point a moral,” without wounding the possessor.

The last portion of the story includes some scenes from the Italian campaign, which had just come to a close while I was writing. If a better experience of Italy than I then possessed might modify some of the opinions I entertained at that time, and induce me to form some conclusions at least at variance with those I then expressed, I still prefer to leave the whole unaltered, lest in changing I might injure the impression under which the fulness of my once conviction had impelled me to pronounce.

Writing these lines now, while men’s hearts are throbbing anxiously for the tidings any day may produce, and when the earth is already tremulous under the march of distant squadrons, I own that even the faint, weak picture of that struggle in this story appeals to myself with a more than common interest. I have no more to add than my grateful acknowledgments to such as still hold me in their favor, and to write myself their devoted servant,

A THEATRE by daylight, a great historical picture in the process of cleaning, a ballet-dancer of a wet day hastening to rehearsal, the favorite for the Oaks dead-lame in a straw-yard, are scarcely more stripped of their legitimate illusions than is a fashionable watering-place on the approach of winter. The gay shops and stalls of flaunting wares are closed; the promenades, lately kept in trimmest order, are weed-grown and neglected; the “sear and yellow leaves” are fluttering and rustling along the alleys where “Beauty’s step was wont to tread.” Both music and fountains have ceased to play; the very statues are putting on great overcoats of snow, while the orange-trees file off like a sad funeral procession to hide themselves in dusky sheds till the coming spring.

You see as you look around you that nature has been as unreal as art itself, and that all the bright hues of foliage and flower, all the odors that floated from bed and parterre, all the rippling flow of stream and fountain, have been just as artistically devised, and as much “got up,” as the transparencies or the Tyrolese singers, the fireworks or the fancy fair, or any other of those ingenious “spectacles” which amuse the grown children of fashion. The few who yet linger seem to have undergone a strange transmutation.

The smiling landlord of the “Adler” we refer particularly to Germany as the very land of watering-places is a half-sulky, farmer-looking personage, busily engaged in storing up his Indian corn and his firewood and his forage, against the season of snows. The bland “croupier,” on whose impassive countenance no shade of fortune was able to mark even a passing emotion, is now seen higgling with a peasant for a sack of charcoal, in all the eagerness of avarice. The trim maiden, whose golden locks and soft blue eyes made the bouquets she sold seem fairer to look on, is a stout wench, whose uncouth fur cap and wooden shoes are the very antidotes to romance. All the transformations take the same sad colors. It is a pantomime read backwards.

Such was Baden-Baden in the November of 182-. Some weeks of bad and broken weather had scattered and dispersed all the gay company. The hotels and assembly-rooms were closed for the winter. The ball-room, which so lately was alight with a thousand tapers, was now barricaded like a jail. The very post-office, around which each morning an eager and pressing crowd used to gather, was shut up, one small aperture alone remaining, as if to show to what a fraction all correspondence had been reduced. The Hotel de Russie was the only house open in the little town; but although the door lay ajar, no busy throng of waiters, no lamps, invited the traveller to believe a hospitable reception might await him within. A very brief glance inside would soon have dispelled any such illusion, had it ever existed. The wide staircase, formerly lined with orange-trees and camellias, was stripped of all its bright foliage; the marble statues were removed; the great thermometer, whose crystal decorations had arrested many a passing look, was now encased within a wooden box, as if its tell-tale face might reveal unpleasant truths, if left exposed.

The spacious “Saal,” where some eighty guests assembled every day, was denuded of all its furniture, mirrors, and lustres; bronzes and pictures were gone, and nothing remained but a huge earthenware stove, within whose grating a faded nosegay left there in summer defied all speculations as to a fire.

In this comfortless chamber three persons now paraded with that quick step and brisk motion that bespeak a walk for warmth and exercise; for dismal as it was within doors, it was still preferable to the scene without, where a cold incessant rain was falling, that, on the hills around, took the form of snow. The last lingerers at a watering-place, like those who cling on to a wreck, have usually something peculiarly sad in their aspect. Unable, as it were, to brave the waves like strong swimmers, they hold on to the last with some vague hope of escape, and, like a shipwrecked crew, drawing closer to each other in adversity than in more prosperous times, they condescend now to acquaintance, and even intimacy, where, before, a mere nod of recognition was alone interchanged. Such were the three who now, buttoned up to the chin, and with hands deeply thrust into side-pockets, paced backwards and forwards, sometimes exchanging a few words, but in that broken and discursive fashion that showed that no tie of mutual taste or companionship had bound them together.

The youngest of the party was a small and very slightly made man of about five or six-and-twenty, whose face, voice, and figure were almost feminine, and, only for a very slight line of black moustache, might have warranted the suspicion of a disguise. His lacquered boots and spotless yellow gloves appeared somewhat out of season, as well as the very light textured coat which he wore; but Mr. Albert Jekyl had been accidentally detained at Baden, waiting for that cruel remittance which, whether the sin be that of agent or relative, is ever so slow of coming. That he bore the inconvenience admirably (and without the slightest show of impatience) it is but fair to confess; and whatever chagrin either the detention, the bad weather, or the solitude may have occasioned, no vestige of discontent appeared upon features where a look of practised courtesy, and a most bland smile, gave the predominant expression. “Who he was,” or, in other words, whence he came, of what family, with what fortune, pursuits, or expectations, we are not ashamed to confess our utter ignorance, seeing that it was shared by all those that tarried that season at Baden, with whom, however, he lived on terms of easy and familiar intercourse.

The next to him was a bilious-looking man, somewhat past the middle of life, with that hard and severe cast of features that rather repels than invites intimacy. In figure he was compactly and stoutly built, his step as he walked, and his air as he stood, showed one whose military training had given the whole tone to his character. Certain strong lines about the mouth, and a peculiar puckering of the angles of the eyes, boded a turn for sarcasm, which all his instincts, and they were Scotch ones, could not completely repress. His voice was loud, sharp, and ringing, the voice of a man who, when he said a thing, would not brook being asked to repeat it. That Colonel Haggerstone knew how to be sapling as well as oak, was a tradition among those who had served with him; still it is right to add, that his more congenial mood was the imperative, and that which he usually practised. The accidental lameness of one of his horses had detained him some weeks at Baden, a durance which assuredly appeared to push his temper to its very last intrenchments.

The third representative of forlorn humanity was a very tall, muscular man, whose jockey-cut green coat and wide-brimmed hat contrasted oddly with a pair of huge white moustaches, that would have done credit to a captain of the Old Guard. On features, originally handsome, time, poverty, and dissipation had left many a mark; but still the half-droll, half-truculent twinkle of his clear gray eyes showed him one whom no turn of fortune could thoroughly subdue, and who, even in the very hardest of his trials, could find heart to indulge his humor for Peter Dalton was an Irishman; and although many years an absentee, held the dear island and its prejudices as green in his memory as though he had left it but a week before.

Such were the three, who, without one sympathy in common, without a point of contact in character, were now drawn into a chance acquaintance by the mere accident of bad weather. Their conversation if such it could be called showed how little progress could be made in intimacy by those whose roads in life lie apart. The bygone season, the company, the play-table and its adventures, were all discussed so often, that nothing remained but the weather. That topic, so inexhaustible to Englishmen, however, offered little variety now, for it had been uniformly bad for some weeks past.

“Where do you propose to pass the winter, sir?” said Haggerstone to Jekyl, after a somewhat lengthy lamentation over the probable condition of all the Alpine passes.

“I ‘ve scarcely thought of it yet,” simpered out the other, with his habitual smile. “There’s no saying where one ought to pitch his tent till the Carnival opens.”

“And you, sir?” asked Haggerstone of his companion on the other side.

“Upon my honor, I don’t know then,” said Dalton; “but I would n’t wonder if I stayed here, or hereabouts.”

“Here! why, this is Tobolsk, sir! You surely couldn’t mean to pass a winter here?”

“I once knew a man who did it,” interposed Jekyl, blandly. “They cleaned him out at ‘the tables;’ and so he had nothing for it but to remain. He made rather a good thing of it, too; for it seems these worthy people, however conversant with the great arts of ruin, had never seen the royal game of thimble-rig; and Frank Mathews walked into them all, and contrived to keep himself in beet-root and boiled beef by his little talents.”

“Was n’t that the fellow who was broke at Kilmagund?” croaked Haggerstone.

“Something happened to him in India; I never well knew what,” simpered Jekyl. “Some said he had caught the cholera; others, that he had got into the Company’s service.”

“By way of a mishap, sir, I suppose,” said the Colonel, tartly.

“He would n’t have minded it, in the least. For certain,” resumed the other, coolly, “he was a sharp-witted fellow; always ready to take the tone of any society.”

The Colonel’s cheek grew yellower, and his eyes sparkled with an angrier lustre; but he made no rejoinder.

“That’s the place to make a fortune, I’m told,” said Dalton. “I hear there’s not the like of it all the world over.”

“Or to spend one,” added Haggerstone, curtly.

“Well, and why not?” replied Dalton. “I ‘m sure it ‘s as pleasant as saving barring a man ‘s a Scotchman.”

“And if he should be, sir? and if he were one that now stands before you?” said Haggerstone, drawing himself proudly up, and looking the other sternly in the face.

“No offence no offence in life. I did n’t mean to hurt your feelings. Sure, a man can’t help where he ‘s going to be born.”

“I fancy we’d all have booked ourselves for a cradle in Buckingham Palace,” interposed Jekyl, “if the matter were optional.”

“Faith! I don’t think so,” broke in Dalton. “Give me back Corrig-O’Neal, as my grandfather Pearce had it, with the whole barony of Kilmurray-O’Mahon, two packs of hounds, and the first cellar in the county, and to the devil I’d fling all the royal residences ever I seen.”

“The sentiment is scarcely a loyal one, sir,” said Haggerstone, “and, as one wearing his Majesty’s cloth, I beg to take the liberty of reminding you of it.”

“Maybe it isn’t; and what then?” said Dalton, over whose good-natured countenance a passing cloud of displeasure lowered.

“Simply, sir, that it shouldn’t be uttered in my presence,” said Haggerstone.

“Phew!” said Dalton, with a long whistle, “is that what you ‘re at? See, now” here he turned fully round, so as to face the Colonel “see, now, I ‘m the dullest fellow in the world at what is called ‘taking a thing up;’ but make it clear for me let me only see what is pleasing to the company, and it is n’t Peter Dalton will balk your fancy.”

“May I venture to remark,” said Jekyl, blandly, “that you are both in error, and however I may (the cold of the season being considered) envy your warmth, it is after all only so much caloric needlessly expended.”

“I was n’t choleric at all,” broke in Dalton, mistaking the word, and thus happily, by the hearty laugh his blunder created, bringing the silly altercation to an end.

“Well,” said Haggerstone, “since we are all so perfectly agreed in our sentiments, we could n’t do better than dine together, and have a bumper to the King’s health.”

“I always dine at two, or half-past,” simpered Jekyl; “besides, I’m on a regimen, and never drink wine.”

“There ‘s nobody likes a bit of conviviality better than myself,” said Dal ton; “but I ‘ve a kind of engagement, a promise I made this morning.”

There was an evident confusion in the way these words were uttered, which did not escape either of the others, who exchanged the most significant glances as he spoke.

“What have we here?” cried Jekyl, as he sprang to the window and looked out. “A courier, by all that’s muddy! Who could have expected such an apparition at this time?”

“What can bring people here now?” said Haggerstone, as with his glass to his eye he surveyed the little well-fed figure, who, in his tawdry jacket all slashed with gold, and heavy jack-boots, was closely locked in the embraces of the landlord.

Jekyl at once issued forth to learn the news, and, although not fully three minutes absent, returned to his companions with a full account of the expected arrivals.

“It’s that rich banker, Sir Stafford Onslow, with his family. They were on their way to Italy, and made a mess of it somehow in the Black Forest they got swept away by a torrent, or crushed by an avalanche, or something of the kind, and Sir Stafford was seized with the gout, and so they ‘ve put back, glad even to make such a port as Baden.”

“If it’s the gout’s the matter with him,” said Dalton, “I ‘ve the finest receipt in the world. Take a pint of spirits poteen if you can get it beat up two eggs and a pat of butter in it; throw in a clove of garlic and a few scrapings of horseradish, let it simmer over the fire for a minute or two, stir it with a sprig of rosemary to give it a flavor, and then drink it off.”

“Gracious Heaven! what a dose!” exclaimed Jekyl, in horror.

“Well, then, I never knew it fail. My father took it for forty years, and there wasn’t a haler man in the country. If it was n’t that he gave up the horseradish for he did n’t like the taste of it he ‘d, maybe, be alive at this hour.”

“The cure was rather slow of operation,” said Haggerstone, with a sneer.

“‘Twas only the more like all remedies for Irish grievances, then,” observed Dal ton, and his face grew a shade graver as he spoke.

“Who was it this Onslow married?” said the Colonel, turning to Jekyl.

“One of the Headworths, I think.”

“Ah, to be sure; Lady Hester. She was a handsome woman when I saw her first, but she fell off sadly; and indeed, if she had not, she ‘d scarcely have condescended to an alliance with a man in trade, even though he were Sir Gilbert Stafford.”

“Sir Gilbert Stafford!” repeated Dalton.

“Yes, sir; and now Sir Gilbert Stafford Onslow. He took the name from that estate in Warwickshire; Skepton Park, I believe they call it.”

“By my conscience, I wish that was the only thing he took,” ejaculated Dalton, with a degree of fervor that astonished the others, “for he took an elegant estate that belonged by right to my wife. Maybe you have heard tell of Corrig-O’Neal?”

Haggerstone shook his head, while with his elbow he nudged his companion, to intimate his total disbelief in the whole narrative.

“Surely you must have heard of the murder of Arthur Godfrey, of Corrig-O’Neal; was n’t the whole world ringing with it?”

Another negative sign answered this appeal.

“Well, well, that beats all ever I heard! but so it is, sorrow bit they care in England if we all murdered each other! Arthur Godfrey, as I was saying, was my wife’s brother, there were just the two of them, Arthur and Jane; she was my wife.”

“Ah! here they come!” exclaimed Jekyl, not sorry for the event which so opportunely interrupted Dalton’s unpromising history. And now a heavy travelling-carriage, loaded with imperials and beset with boxes, was dragged up to the door by six smoking horses. The courier and the landlord were immediately in attendance, and after a brief delay the steps were lowered, and a short, stout man, with a very red face and a very yellow wig, descended, and assisted a lady to alight. She was a tall woman, whose figure and carriage were characterized by an air of fashion. After her came a younger lady; and lastly, moving with great difficulty, and showing by his worn looks and enfeebled frame the suffering he had endured, came a very thin, mild-looking man of about sixty. Leaning upon the arm of the courier at one side, and of his stout companion, whom he called Doctor, at the other, he slowly followed the ladies into the house. They had scarcely disappeared when a caleche, drawn by three horses at a sharp gallop, drew up, and a young fellow sprang out, whose easy gestures and active movements showed that all the enjoyments of wealth and all the blandishments of fashion had not undermined the elastic vigor of body which young Englishmen owe to the practice of field sports.

“This place quite deserted, I suppose,” cried he, addressing the landlord. “No one here?”

“No one, sir. All gone,” was the reply.

Haggerstone’s head shook with a movement of impatience as he heard this remark, disparaging as it was, to his own importance; but he said nothing, and resumed his walk as before.

“Our Irish friend is gone away, I perceive,” said Jekyl, as he looked around in vain for Dalton. “Do you believe all that story of the estate he told us?”

“Not a syllable of it, sir. I never yet met an Irishman and it has been my lot to know some scores of them who had not been cheated out of a magnificent property, and was not related to half the peerage to boot. Now, I take it that our highly connected friend is rather out at elbows!” And he laughed his own peculiar hard laugh, as though the mere fancy of another man’s poverty was something inconceivably pleasant and amusing.

“Dinner, sir,” said the waiter, entering and addressing the Colonel.

“Glad of it,” cried he; “it’s the only way to kill time in this cursed place;” and so saying, and without the ceremony of a good-bye to his companion, the Colonel bustled out of the room with a step intended to represent extreme youth and activity. “That gentleman dines at two?” asked he of the waiter, as he followed him up the stairs.

“He has not dined at all, sir, for some days back,” said the waiter. “A cup of coffee in the morning, and a biscuit, are all that he takes.”

The Colonel made an expressive gesture by turning out the lining of his pocket.

“Yes, sir,” replied the other, significantly; “very much that way, I believe.” And with that he uncovered the soup, and the Colonel arranged his napkin and prepared to dine.

WHEN Dalton parted from his companions at the “Russie,” it was to proceed by many an intricate and narrow passage to a remote part of the upper town, where close to the garden wall of the Ducal Palace stood, and still stands, a little solitary two-storied house, framed in wood, and the partitions displaying some very faded traces of fresco painting. Here was the well-known shop of a toy-maker; and although now closely barred and shuttered, in summer many a gay and merry troop of children devoured with eager eyes the treasures of Hans Roeckle.

Entering a dark and narrow passage beside the shop, Dalton ascended the little creaking stairs which led to the second story. The landing place was covered with firewood, great branches of newly-hewn beech and oak, in the midst of which stood a youth, hatchet in hand, busily engaged in chopping and splitting the heavy masses around him. The flush of exercise upon his cheek suited well the character of a figure which, clothed only in shirt and trousers, presented a perfect picture of youthful health and symmetry.

“Tired, Frank?” asked the old man, as he came up.

“Tired, father! not a bit of it. I only wish I had as much more to split for you, since the winter will be a cold one.”

“Come in and sit down, boy, now,” said the father, with a slight tremor as he spoke. “We cannot have many more opportunities of talking together. To-morrow is the 28th of November.”

“Yes; and I must be in Vienna by the fourth, so Uncle Stephen writes.”

“You must not call him uncle, Frank, he forbids it himself; besides, he is my uncle, and not yours. My father and he were brothers, but never saw each other after fifteen years of age, when the Count that ‘s what we always called him entered the Austrian service, so that we are all strangers to each other.”

“His letter does n’t show any lively desire for a closer intimacy,” said the boy, laughing. “A droll composition it is, spelling and all.”

“He left Ireland when he was a child, and lucky he was to do so,” sighed Dalton, heavily. “I wish I had done the same.”

The chamber into which they entered was, although scrupulously clean and neat, marked by every sign of poverty. The furniture was scanty and of the humblest kind; the table linen, such as used by the peasantry, while the great jug of water that stood on the board seemed the very climax of narrow fortune in a land where the very poorest are wine-drinkers.

A small knapsack with a light travelling-cap on it, and a staff beside it, seemed to attract Dalton’s eyes as he sat down. “It is but a poor equipment, that yonder. Frank,” said he at last, with a forced smile.

“The easier carried,” replied the lad, gayly.

“Very true,” sighed the other. “You must make the journey on foot.”

“And why not, father? Of what use all this good blood, of which I have been told so often and so much, if it will not enable a man to compete with the low-born peasant. And see how well this knapsack sits,” cried he, as he threw it on his shoulder. “I doubt if the Emperor’s pack will be as pleasant to carry.”

“So long as you haven’t to carry a heavy heart, boy,” said Dalton, with deep emotion, “I believe no load is too much.”

“If it were not for leaving you and the girls, I never could be happier, never more full of hope, father. Why should not I win my way upward as Count Stephen has done? Loyalty and courage are not the birthright of only one of our name!”

“Bad luck was all the birthright ever I inherited,” said the old man, passionately; “bad luck in everything I touched through life! Where others grew rich, I became a beggar; where they found happiness, I met misery and ruin! But it’s not of this I ought to be thinking now,” cried he, changing his tone. “Let us see, where are the girls?” And so saying, he entered a little kitchen which adjoined the room, and where, engaged in the task of preparing the dinner, was a girl, who, though several years older, bore a striking resemblance to the boy. Over features that must once have been the very type of buoyant gayety, years of sorrow and suffering had left their deep traces, and the dark circles around the eyes betrayed how deeply she had known affliction. Ellen Dalton’s figure was faulty for want of height in proportion to her size, but had another and more grievous defect in a lameness, which made her walk with the greatest difficulty. This was the consequence of an accident when riding, a horse having fallen upon her and fractured the hip-bone. It was said, too, that she had been engaged to be married at the time, but that her lover, shocked by the disfigurement, had broken off the match, and thus made this calamity the sorrow of a life long.

“Where’s Kate?” said the father, as he cast a glance around the chamber.

Ellen drew near, and whispered a few words in his ear.

“Not in this dreadful weather; surely, Ellen, you didn’t let her go out in such a night as this?”

“Hush!” murmured she, “Frank will hear you; and remember, father, it is his last night with us.”

“Could n’t old Andy have found the place?” asked Daiton; and as he spoke, he turned his eyes to a corner of the kitchen, where a little old man sat in a straw chair peeling turnips, while he croned a ditty to himself in a low singsong tone; his thin, wizened features, browned by years and smoke, his small scratch wig, and the remains of an old scarlet hunting-coat that he wore, giving him the strongest resemblance to one of the monkeys one sees in a street exhibition.

“Poor Andy!” cried Ellen, “he’d have lost his way twenty times before he got to the bridge.”

“Faith, then, he must be greatly altered,” said Dalton, “for I ‘ve seen him track a fox for twenty miles of ground, when not a dog of the pack could come on the trace. Eh, Andy!” cried he, aloud, and stooping down so as to be heard by the old man, “do you remember the cover at Corralin?”

“Don’t ask him, father,” said Ellen, eagerly; “he cannot sleep for the whole night after his old memories have been awakened.”

The spell, however, had begun to work; and the old man, letting fall both knife and turnip, placed his hands on his knees, and in a weak, reedy treble began a strange, monotonous kind of air, as if to remind himself of the words, which, after a minute or two, he remembered thus.

“There was old Tom Whaley,

And Anthony Baillie,

And Fitzgerald, the Knight of Glynn,

And Father Clare,

On his big brown mare,

That moruin’ at Corralin!”

“Well done, Andy! well done!” exclaimed Dalton. “You ‘re as fresh as a four-year-old.”

“Iss!” said Andy, and went on with his song.

“And Miles O’Shea,

On his cropped tail bay,

Was soon seen ridin’ in.

He was vexed and crossed

At the light hoar frost,

That mornin’ at Corralin.”

“Go on, Andy! go on, my boy!” exclaimed Dalton, in a rapture at the words that reminded him of many a day in the field and many a night’s carouse. “What comes next?”

“Ay!” cried Andy.

“Says he, ‘When the wind

Laves no scent behind,

To keep the dogs out ‘s a sin;

I ‘ll be d—d if I stay,

To lose my day,

This mornin’ at Corralin.’”

But ye see he was out in his reck’nin’!” cried Andy; “for, as if

“To give him the lie,

There rose a cry,

As the hounds came yelpin’ in;

And from every throat

There swelled one note,

That moruin’ at Corralin.”

A fit of coughing, brought on by a vigorous attempt to imitate the cry of a pack, here closed Andy’s minstrelsy; and Ellen, who seemed to have anticipated some such catastrophe, now induced her father to return to the sitting-room, while she proceeded to use those principles of domestic medicine clapping on the back and cold water usually deemed of efficacy in like cases.

“There now, no more singing, but take up your knife and do what I bade you,” said she, affecting an air of rebuke; while the old man, whose perceptions did not rise above those of a spaniel, hung down his head in silence. At the same moment the outer door of the kitchen opened, and Kate Dalton entered. Taller and several years younger than her sister, she was in the full pride of that beauty of which blue eyes and dark hair are the chief characteristics, and is deemed by many as peculiarly Irish. Delicately fair, and with features regular as a Grecian model, there was a look of brilliant, almost of haughty, defiance about her, to which her gait and carriage seemed to contribute; nor could the humble character of her dress, where strictest poverty declared itself, disguise the sentiment.

“How soon you’re back, dearest!” said Ellen, as she took off the dripping cloak from her sister’s shoulders.

“And only think, Ellen, I was obliged to go to Lichtenthal, where little Hans spends all his evenings in the winter season, at the ‘Hahn!’ And just fancy his gallantry! He would see me home, and would hold up the umbrella, too, over my head, although it kept his own arm at full stretch; while, by the pace we walked, I did as much for his legs. It is very ungrateful to laugh at him, for he said a hundred pretty things to me, about my courage to venture out in such weather, about my accent as I spoke German, and lastly, in praise of my skill as a sculptor. Only fancy, Ellen, what a humiliation for me to confess that these pretty devices were yours, and not mine; and that my craft went no further than seeking for the material which your genius was to fashion.”

“Genius, Kate!” exclaimed Ellen, laughing. “Has Master Hans been giving you a lesson in flattery; but tell me of your success which has he taken?”

“All everything!” cried Kate; “for although at the beginning the little fellow would select one figure and then change it for another, it was easy to see that he could not bring himself to part with any of them: now sitting down in rapture before the ‘Travelling Student,’ now gazing delightedly at the ‘Charcoal-Burners,’ but all his warmest enthusiasm bursting forth as I produced the ‘Forest Maiden at the Well.’ He did, indeed, think the ‘Pedler’ too handsome, but he found no such fault with the Maiden: and here, dearest, here are the proceeds, for I told him that we must have ducats in shining gold for Frank’s new crimson purse; and here they are;” and she held up a purse of gay colors, through whose meshes the bright metal glittered.

“Poor Hans!” said Ellen, feelingly. “It is seldom that so humble an artist meets so generous a patron.”

“He’s coming to-night,” said Kate, as she smoothed down the braids of her glossy hair before a little glass, “he’s coming to say good-bye to Frank.”

“He is so fond of Frank.”

“And of Frank’s sister Nelly; nay, no blushing, dearest; for myself, I am free to own admiration never comes amiss, even when offered by as humble a creature as the dwarf, Hans Roeckle.”

“For shame, Kate, for shame! It is this idle vanity that stifles honest pride, as rank weeds destroy the soil for wholesome plants to live in.”

“It is very well for you, Nelly, to talk of pride, but poor things like myself are fain to content themselves with the baser metal, and even put up with vanity! There, now, no sermons, no seriousness; I’ll listen to nothing to-day that savors of sadness, and, as I hear pa and Frank laughing, I’ll be of the party.”

The glance of affection and admiration which Ellen bestowed upon her sister was not unmixed with an expression of painful anxiety, and the sigh that escaped her told with what tender interest she watched over her.

The little dinner, prepared with more than usual care, at length appeared, and the family sat around the humble board with a sense of happiness dashed by one only reflection, that on the morrow Frank’s place would be vacant.

Still each exerted himself to overcome the sadness of that thought, or even to dally with it, as one suggestive of pleasure; and when Ellen placed unexpectedly a great flask of Margraer before them to drink the young soldier’s health, the zest and merriment rose to the highest. Nor was old Andy forgotten in the general joy. A large bumper of wine was put before him, and the door of the sitting-room left open, as if to let him participate in the merry noises that prevailed there. How naturally, and instinctively, too, their hopes gave color to all they said, as they told each other that the occasion was a happy one! that dear Frank would soon be an officer, and of course distinguished by the favor of some one high in power; and lastly, they dwelt with such complacency on the affectionate regard and influence of “Count Stephen” as certain to secure the youth’s advancement. They had often heard of the Count’s great military fame, and the esteem in which he was held by the Court of Vienna; and now they speculated on the delight it would afford the old warrior who had never been married himself to have one like Frank, to assist by his patronage, and promote by his influence, and with such enthusiasm did they discuss the point, that at last they actually persuaded themselves that Frank’s entering the service was a species of devotion to his relative’s interest, by affording him an object worthy of his regard and affection.

While Ellen loved to dwell upon the great advantages of one who should be like a father to the boy, aiding him by wise counsel, and guiding him in every difficulty, Kate preferred to fancy the Count introducing Frank into all the brilliant society of the splendid capital, presenting him to those whose acquaintance was distinction, and at once launching him into the world of fashion and enjoyment. The promptitude with which he acceded to their father’s application on Frank’s behalf, was constantly referred to as the evidence of his affectionate feeling for the family; and if his one solitary letter was of the very briefest and driest of all epistolary essays, they accounted for this very naturally by the length of time which had elapsed since he had either spoken or written his native language.

In the midst of these self-gratulations and pleasant fancies the door opened, and Hans Roeckle appeared, covered from head to foot by a light hoar-frost, that made him look like the figure with which an ingenious confectioner sometimes decorates a cake. The dwarf stood staring at the signs of a conviviality so new and unexpected.

“Is this Christmas time, or Holy Monday, or the Three Kings’ festival, or what is it, that I see you all feasting?” cried Hans, shaking the snow off his hat, and proceeding to remove a cloak which he had draped over his shoulder in most artistic folds.

“We were drinking Frank’s health, Master Hans,” said Dalton, “before he leaves us. Come over and pledge him too, and wish him all success, and that he may live to be a good and valued soldier of the Emperor.”

Hans had by this time taken off his cloak, which, by mounting on a chair, he contrived to hang up, and now approached the table with great solemnity, a pair of immense boots of Russian leather, that reached to his hips, giving him a peculiarly cumbrous and heavy gait; but these, as well as a long vest of rabbit skins that buttoned close to the neck, made his invariable costume in the winter.

“I drink,” said the dwarf, as, filling a bumper, he turned to each of the company severally “I drink to the venerable father and the fair maidens, and the promising youth of this good family, and I wish them every blessing good Christians ought to ask for; but as for killing and slaying, for burning villages and laying waste cities, I ‘ve no sympathy with these.”

“But you are speaking of barbarous times, Master Hans,” said Kate, whose cheek mantled into scarlet as she spoke, “when to be strong was to be cruel, and when ill-disciplined hordes tyrannized over good citizens.”

“I am talking of soldiers, such as the world has ever seen them,” cried Hans, passionately; but of whose military experiences, it is but fair to say, his own little toyshop supplied all the source. “What are they?” cried he, “but toys that never last, whether he who plays with them be child or kaiser! always getting smashed, heads knocked off here, arms and legs astray there; ay, and strangest of all, thought most of when most disabled! and then at last packed up in a box or a barrack, it matters not which, to be forgotten and seen no more! Hadst thou thought of something useful, boy some good craft, a Jager with a corkscrew inside of him, a tailor that turns into a pair of snuffers, a Dutch lady that makes a pin-cushion, these are toys people don’t weary of but a soldier! to stand ever thus” and Hans shouldered the fire-shovel, and stood “at the present.” “To wheel about so walk ten steps here ten back there never so much as a glance at the pretty girl who is passing close beside you.” Here he gave a look of such indescribable tenderness towards Kate, that the whole party burst into a fit of laughter. “They would have drawn me for the conscription,” said Hans, proudly, “but I was the only son of a widow, and they could not.”

“And are you never grieved to think what glorious opportunities of distinction have been thus lost to you?” said Kate, who, notwithstanding Ellen’s imploring looks, could not resist the temptation of amusing herself with the dwarf’s vanity.

“I have never suffered that thought to weigh upon me,” cried Hans, with the most unsuspecting simplicity. “It is true, I might have risen to rank and honors; but how would they have suited me, or I them? Or how should I have made those dearest to me sharers in a fortune so unbecoming to us? Think of poor Hans’s old mother, if her son were to ask her blessing with a coat all glittering with stars and crosses; and then think of her as I have seen her, when I go, as I do every year, to visit her in the Bregentzer Wald, when she comes out to meet me with our whole village, proud of her son, and yet not ashamed of herself. That is glory that is distinction enough for Hans Roeckle.”

The earnestness of his voice, and the honest manliness of his sentiments, were more than enough to cover the venial errors of a vanity that was all simplicity. It is true that Hans saw the world only through the medium of his own calling, and that not a very exalted one; but still there went through all the narrowness of his views a tone of kindliness a hearty spirit of benevolence, that made his simplicity at times rise into something almost akin to wisdom. He had known the Dal tons as his tenants, and soon perceived that they were not like those rich English, from whom his countrymen derive such abundant gains. He saw them arrive at a season when all others were taking their departure, and detected in all their efforts at economy, not alone that they were poor, but, sadder still, that they were of those who seem never to accustom themselves to the privations of narrow fortune; for, while some submit in patience to their humble lot, with others life is one long and hard-fought struggle, wherein health, hope, and temper are expended in vain. That the Daltons maintained a distance and reserve towards others of like fortune did, indeed, puzzle honest Hans, perhaps it displeased him, too, for he thought it might be pride; but then their treatment of himself disarmed that suspicion, for they not only received him ever cordially, but with every sign of real affection; and what was he to expect such? Nor were these the only traits that fascinated him; for all the rugged shell the kernel was a heart as tender, as warm, and as full of generous emotions as ever beat within an ampler breast. The two sisters, in Hans’s eyes, were alike beautiful; each had some grace or charm that he had never met with before, nor could he ever satisfy himself whether his fancy was more taken by Kate’s wit or by Ellen’s gentleness.

If anything were needed to complete the measure of his admiration, their skill in carving those wooden figures, which he sold, would have been sufficient. These were in his eyes nor was he a mean connoisseur high efforts of genius; and Hans saw in them a poetry and a truthfulness to nature that such productions rarely, if ever, possess. To sell, such things as mere toys, he regarded as little short of a sacrilege, while even to part with them at all cost him a pang like that the gold-worker of Florence experienced when he saw some treasure of Benvenuto’s chisel leave his possession. Not, indeed, that honest Hans had to struggle against that criminal passion which prompted the jeweller, even by deeds of assassination, to repossess himself of the coveted objects; nay, on the contrary, he felt a kindness and a degree of interest towards those in whose keeping they were, as if some secret sympathy united them to each other.

Is it any wonder if poor Hans forgot himself in such pleasant company, and sat a full hour and a half longer than he ought? To him the little intervals of silence that were occasionally suffered to intervene were but moments of dreamy and delicious revery, wherein his fancy wandered away in a thousand pleasant paths; and when at last the watchman for remember, good reader, they were in that primitive Germany where customs change not too abruptly announced two o’clock, little Hans did not vouchsafe a grateful response to the quaint old rhyme that was chanted beneath the window.

“That little chap would sit to the day of judgment, and never ask to wet his lips,” said Dal ton, as Frank accompanied the dwarf downstairs to the street door.

“I believe he not only forgot the hour, but where he was, and everything else,” said Kate.

“And poor Frank! who should have been in bed some hours ago,” sighed Nelly.

“Gone at last, girls!” exclaimed Frank, as he entered, laughing. “If it hadn’t been a gust of wind that caught him at the door, and carried him clean away, our leave-taking might have lasted till morning. Poor fellow! he had so many cautions to give me, such mountains of good counsel; and see, here is a holy medal he made me accept. He told me the ‘Swedes’ would never harm me so long as I wore it; he still fancies that we are in the Thirty Years’ War.”

In a hearty laugh over Hans Roeckle’s political knowledge, they wished each other an affectionate good-night, and separated. Frank was to have his breakfast by daybreak, and each sister affected to leave the care of that meal to the other, secretly resolving to be up and stirring first.

Save old Andy, there was not one disposed to sleep that night. All were too full of their own cares. Even Dalton himself, blunted as were his feelings by a long life of suffering, his mind was tortured by anxieties; and one sad question arose again and again before him, without an answer ever occurring: “What is to become of the girls when I am gone? Without a home, they will soon be without a protector!” The bright fancies, the hopeful visions in which the evening had been passed, made the revulsion to these gloomy thoughts the darker. He lay with his hands pressed upon his face, while the hot tears gushed from eyes that never before knew weeping.

At moments he half resolved not to let Frank depart, but an instant’s thought showed him how futile would be the change. It would be but leaving him to share the poverty, to depend upon the scanty pittance already too little for themselves. “Would Count Stephen befriend the poor girls?” he asked himself over and over; and in his difficulty he turned to the strange epistle in which the old general announced Frank’s appointment as a cadet.

The paper, the square folding, the straight, stiff letters, well suited a style which plainly proclaimed how many years his English had lain at rest. The note ran thus:

GRABEN-WIEN, Octobre 9, 18—

WORTHY SIR AND NEPHEW, Your kindly greeting, but long-time

on-the-road-coming letter is in my hands. It is to me

pleasure that I announce the appointment of your son as a

Cadet in the seventh battalion of the Carl-Franz Infanterie.

So with, let him in all speed of time report himself here at

Wien, before the War’s Minister, bringing his Tauf schein

Baptism’s sign as proof of Individualism.

I am yours, well to command, and much-loving kinsman,

GRAF DALTON VON AUERSBERG, Lieut.-General and

Feldzeugmeister, K.K.A.

To the high and well-born, the Freiherr v. Dalton, in Baden Baden.

THIS dry epistle Dalton read and re-read, trying, if not to discover some touch of kindliness or interest, to detect, at least, some clew to its writer’s nature; but to no use, its quaint formalism baffled all speculation, and he gave up the pursuit in despair. That “the Count” was his father’s only brother, and a “Dalton,” were the only grains of comfort he could extract from his meditations; but he had lived long enough in the world to know how little binding were the ties of kindred when once slackened by years and distance. The Count might, therefore, regard them in the light of intruders, and feel the very reverse of pleasure at the revival of a relationship which had slept for more than half a century. Dalton’s pride or what he thought his pride revolted against this thought; for, although this same pride would not have withheld him from asking a favor of the Count, it would have assumed a most indignant attitude if refused, or even grudgingly accorded.

When the thought first occurred to him of applying to his uncle in Frank’s behalf, he never hesitated about the propriety of addressing a request to one with whom he had never interchanged a line in all his life; and now he was quite ready to take offence, if all the warmth of blood relationship should not fill the heart of him who had been an exile from home and family since his earliest boyhood.

An easy, indolent selfishness had been the spirit of Dalton’s whole life. He liked to keep a good house, and to see company about him; and this obtained for him the reputation of hospitality. He disliked unpopularity, and dreaded the “bad word” of the people; and hence he suffered his tenantry to fall into arrears and his estate into ruin. A vain rivalry with wealthier neighbors prevented retrenchment when his means were lessened. The unthinking selfishness of his nature was apparent even in his marriage, since it was in obedience to an old pledge extracted years before that Miss Godfrey accepted him, and parted in anger with her brother, who had ever loved her with the warmest affection. Mr. Godfrey never forgave his sister; and at his death, the mysterious’ circumstances of which were never cleared up, his estate passed to a distant relative, the rick Sir Gilbert Stafford.

Dalton, who long cherished the hope of a reconciliation, saw all prospect vanish when his wife died, which she did, it was said, of a broken heart. His debts were already considerable, and all the resources of borrowing and mortgage had been long since exhausted; nothing was then left for him but an arrangement with his creditors, which, giving him a pittance scarcely above the very closest poverty, enabled him to drag out life in the cheap places of the Continent; and thus, for nigh twenty years, had he wandered about from Dieppe to Ostend, to Bruges, to Dusseldorf, to Coblentz, and so on, among the small Ducal cities, till, with still failing fortune, he was fain to seek a residence for the winter in Baden, where house-rent, at least, would be almost saved to him.

The same apathy that had brought on his ruin enabled him to bear it. Nothing has such a mock resemblance to wisdom as utter heartlessness; with all the seeming of true philosophy, it assumes a port and bearing above the trials of the world; holds on “the even tenor of its way,” undeterred by the reverses which overwhelm others, and even meets the sternest frowns of fortune with the bland smile of equanimity.

In this way Dalton had deceived many who had known him in better days, and who now saw him, even in his adversity, with the same careless, good-natured look, as when he took the field with his own hounds, or passed round the claret at his own table. Even his own children were sharers in this delusion, and heard him with wondering admiration, as he told of the life he used to lead, and the style he once kept up at Mount Dalton. These were his favorite topics; and, as he grew older, he seemed to find a kind of consolation in contrasting all the hard rubs of present adversity with his once splendor.

Upon Ellen Dalton, who had known and could still remember her mother, these recitals produced an impression of profound grief, associated as they were with the sufferings of a sick-bed and the closing sorrows of a life; while, in the others, they served to keep up a species of pride of birth, and an assumption of superiority to others of like fortune, which their father gloried in, representing, as he used to say, “the old spirit of the Dal tons.”

As for Kate, she felt it a compensation for present poverty to know that they were of gentle blood, and that if fortune, at some distant future, would deal kindly by them, to think that they should not obtrude themselves like upstarts on the world, but resume, as it were, the place that was long their own.

In Frank the evil had taken a deeper root. Taught from his earliest infancy to believe himself the heir of an ancient house, pride of birth and station instilled into his mind by old Andy, the huntsman, the only dependant, whom, with characteristic wisdom, they had carried with them from Ireland, he never ceased to ponder on the subject, and wonder within himself if he should live to have “his own” again.

Such a hold had this passion taken of him, that, even as a child, he would wander away for days long into lonely and unfrequented spots, thinking over the stories he had heard, and trying to conjure up before his eyes some resemblance to that ancient house and venerable domain which had been so long in his family. It was no part of his teaching to know by what spendthrift and reckless waste, by what a long career of folly, extravagance, and dissipation, the fortune of his family had been wrecked; or rather, many vague and shadowy suspicions had been left to fester in his mind of wrongs and injuries done them; of severe laws imposed by English ignorance or cruelty; of injustice, on this hand heartless indifference of friends on the other; the unrelenting anger of his uncle Godfrey filling up the measure of their calamities. Frank Dalton’s education went very little further than this; but, bad as it was, its effect was blunted by the natural frankness and generosity of his character, its worst fruits being an over-estimate of himself and his pretensions, errors which the world has always the watchful kindness to correct in those who wear threadbare coats and patched boots.

He was warmly and devotedly attached to his father and sisters, and whatever bitterness found its way into his heart was from seeing them enduring the many trials of poverty.

All his enthusiasm for the service in which he was about to enter was, therefore, barely sufficient to overcome the sorrow of parting with those, whom alone of all the world he loved; and when the moment drew nigh for his departure, he forgot the bright illusions by which he had so often fed his hopes, and could only think of the grief of separation.

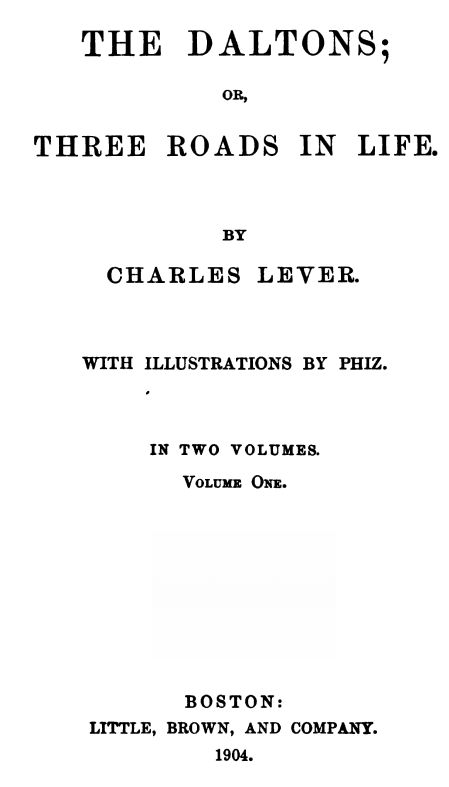

His candle had burned down nearly to the socket, when he arose and looked at his watch. It was all dark as midnight without, although nigh six o’clock. He opened the window, and a thin snowdrift came slanting in, borne on a cutting north wind; he closed it hastily, and shuddered as he thought of the long and lonely march before him. All was silent in the house as he dressed himself and prepared for the road. With noiseless step he drew near his father’s door and listened; everything was still. He could not bring himself to disturb him, so he passed on to the room where his sisters slept. The door lay ajar, and a candle was burning on the table. Frank entered on tiptoe and drew near the bed, but it was empty and had not been lain in. As he turned round he beheld Kate asleep in a chair, dressed as he had last seen her. She had never lain down, and the prayer-book, which had dropped from her hand, told how her last waking moments were passed.

He kissed her twice, but even the hot tears that fell from his eyes upon her cheek did not break her slumber. He looked about him for some token to leave, that might tell he had been there, but there was nothing, and, with a low sigh, he stole from the room.

As he passed out into the kitchen, Ellen was there. She had already prepared his breakfast, and was spreading the table when he entered.

“How good of you how kind, Ellen,” said he, as he passed his arm around her neck.

“Hush, Frank, they are both sleeping. Poor papa never closed his eyes till half an hour ago, and Kate was fairly overcome ere she yielded.”

“You will say that I kissed them, Nelly, kissed them twice,” said he, in a low, broken voice, “and that I could n’t bear to awake them. Leave-taking is so sorrowful. Oh, Ellen, if I knew that you were all happy, that there were no hardships before you, when I ‘m away!”

“And why should we not, Frank?” said she, firmly. “There is no dishonor in this poverty, so long as there are no straits to make it seem other than it is. Let us rather pray for the spirit that may befit any lot we are thrown in, than for a fortune to which we might be unsuited.”

“Would you forget who we are, Ellen?” said he, half reproachfully.

“I would remember it, Frank, in a temper less of pride than humility.”

“I do not see much of the family spirit in all this,” rejoined he, almost angrily.

“The family spirit,” echoed she, feelingly. “What has it ever done for us, save injury? Has it suggested a high=bearing courage against the ills of narrow fortune? Has it told us how to bear poverty with dignity, or taught us one single lesson of patience and submission? Or has it, on the contrary, been ever present to whisper the changes in our condition how altered our lot making us ashamed of that companionship which our station rendered possible for us, and leaving us in the isolation of friendlessness for the sake of I blush to abuse the word our Pride! Oh, Frank, my dear, dear brother, take it not ill of me, that in our last moments together, perhaps for years, I speak what may jar upon your ears to hear; but remember that I am much older, that I have seen far more of the world, at least of its sorrows and cares, than you have. I have indeed known affliction in many ways, but have never found a poorer comforter in its troubles than what we call our Pride!”

“You would have me forget I am a Dalton, then?” said the boy, in a tone of sorrowful meaning.

“Never! when the recollection could prompt a generous or a noble action, a manly ambition, or a high-hearted thought; but the name will have no spell in it, if used to instil an imperious, discontented spirit, a regretful contrast of what we are, with what we might have been, or what, in a worldly sense, is more destructive still, a false reliance on the distinction of a family to which we have contributed nothing.”

“You do not know, Nelly dearest, of what a comfort you have robbed me,” said Frank, sorrowfully.

“Do not say so, my dearest brother,” cried she, passing her arm around him; “a deception, a mere illusion, is unworthy of that name. Look above the gratification of mere vanity, and you will become steeled against the many wounds self-love is sure to receive in intercourse with the world. I cannot tell how, or with what associates, you are about to live, but I feel certain that in every station a man of truth and honor will make himself respected. Be such, dearest Frank. If family pride if the name of Dalton have value in your eyes, remember that upon you it rests to assert its right to distinction. If, as I would fondly hope, your heart dwells here with us, bethink ye what joy what holy gratitude you will diffuse around our humble hearth to know that our brother is a good man.”

It was some moments ere either could speak again. Emotions, very different ones, perhaps, filled their hearts, and each was too deeply moved for words. Frank’s eyes were full of tears, and his cheek quivering, as he threw his knapsack on his shoulder.

“You will write from Innspruck, Frank; but how many days will it take ere you reach that city?”

“Twelve or fourteen at least, if I go on foot. There, Nelly, do not help me, dearest; I shall not have you tomorrow to fasten these straps.”

“This is not to be forgotten, Frank; it’s Kate’s present. How sorry she will be not to have given it with her own hands!” And so saying, she gave him the purse her sister had worked.

“But there is gold in it,” said the boy, growing pale with emotion.

“Very little, Frank dearest,” replied she, smiling. “A cadet must always have gold in his purse, so little Hans tells us; and you know how wise he is in all these matters.”

“And is it from a home like this that I am to take gold away!” cried he, passionately.

“Nay, Frank, you must not persuade us that we are so very poor. I will not consent to any sense of martyrdom, I promise you.” It was not without difficulty she could overcome his scruples; nor, perhaps, had she succeeded at all, if his thoughts had not been diverted into another channel by a light tapping at the door. It was Hans Roeckle come to awake him.

Again and again the brother and sister embraced; and in a very agony of tears Frank tore himself away, and hastened down the stairs. The next moment the heavy house door banged loudly, and he was gone.

Oh, the loneliness of mind in which he threaded his way through the dark and narrow streets, where the snow already lay deeply! With what sinking of the heart he turned to look for the last time at the window where the light the only one to be seen still glimmered. How little could all the promptings of hope suffice against the sad and dark reality that he was leaving all he loved, and all who loved him, to adventure upon a world where all was bleak and friendless!

But not all his dark forebodings could equal hers from whom he had just parted. Loving her brother with an affection more like that of mother than sister, she had often thought over the traits of his character, where, with many a noble gift, the evil seeds of wrong teaching had left, like tall weeds among flowers, the baneful errors of inordinate self-esteem and pride. Ignorant of the career on which he was about to enter, Ellen could but speculate vaguely how such a character would be esteemed, and whether his native frankness and generosity would cover over, or make appear as foibles, these graver faults. Their own narrow fortunes, the very straits and privations of poverty, with all their cruel wounds to honest pride, and all their sore trials of temper, she could bear up against with an undaunted courage. She had learned her lesson in the only school wherein it is taught, and daily habit had instilled its own powers of endurance; but, for Frank, her ambition hoped a higher and brighter destiny, and now, in her solitude, and with a swelling heart, she knelt down and prayed for him. And, oh! if the utter ings of such devotion never rise to Heaven or meet acceptance there, they at least bring balm to the spirit of him who syllables them, building up a hope whose foundations are above the casualties of humanity, and giving a courage that mere self-reliance never gave.

Little Hans not only came to awaken Frank, but to give him companionship for some miles of his way, a thoughtful kindness, for which the youth’s deep preoccupation seemed to offer but a poor return. Indeed, Frank scarcely knew that he was not travelling in utter solitude, and all the skilful devices of the worthy dwarf to turn the channel of his thoughts were fruitless. Had there been sufficient light to have surveyed the equipment of his companion, it is more than probable that the sight would have done more to produce this diversion of gloom than any arguments which could have been used. Master Roeckle, whose mind was a perfect storehouse of German horrors, earthly and unearthly, and who imagined that a great majority of the human population of the globe were either bandits or witches, had surrounded himself with a whole museum of amulets and charms of various kinds. In his cap he wore the tail of a black squirrel, as a safeguard against the “Forest Imp;” a large dried toad hung around his neck, like an order, to protect him from the evil eye; a duck’s foot was fastened to the tassel of his boot, as a talisman against drowning; while strings of medals, coins, precious stones, blessed beads, and dried insects, hung round and about him in every direction. Of all the portions of his equipment, however, what seemed the most absurd was a huge pole-axe of the fifteenth century, and which he carried as a defence against mere mortal foes, but which, from its weight and size, appeared far more likely to lay its bearer low than inflict injury upon others. It had been originally stored up in the Rust Kammer, at Prague, and was said to be the identical weapon with which Conrad slew the giant at Leutmeritz, a fact which warranted Hans in expending two hundred florins in purchasing it; as, to use his own emphatic words, “it was not every day one knew where to find the weapon to bring down a giant.”

As Hans, encumbered by his various adjuncts, trotted along beside his stalwart companion, he soon discovered that all his conversational ability to exert which cost him so dearly was utterly unattended to; he fell into a moody silence, and thus they journeyed for miles of way without interchanging a word. At last they came in sight of the little village of Hernitz Kretschen, whence by a by road Frank was to reach the regular line that leads through the Hohlen Thai to the Lake of Constance, and where they were to part.

“I feel as though I could almost go all the way with you,” said Hans, as they stopped to gaze upon the little valley where lay the village, and beyond which stretched a deep forest of dark pine-trees, traversed by a single road.

“Nay, Hans,” said Frank, smiling, as for the first time he beheld the strange figure beside him; “you must go back to your pleasant little village and live happily, to do many a kindness to others, as you have done to me to-day!”

“I would like to take service with the Empress myself,” said Hans, “if it were for some good and great cause, like the defence of the Church against the Turks, or the extermination of the race of dragons that infest the Lower Danube.”

“But you forget, Hans, it is an Emperor, rules over Austria now,” said Frank, preferring to offer a correction to the less startling of his hallucinations.

“No, no, Master Frank, they have not deposed the good Maria Teresa, they would never do that. I saw her picture over the doorway of the Burgermeister the last time I went to visit my mother in the Bregertzer Wald, and by the same token her crown and sceptre were just newly gilt, a thing they would not have done if she were not on the throne.”

“What if she were dead, and her son too?” said Frank; but his words were scarce uttered when he regretted to have said them, so striking was the change that came over the dwarf’s features.

“If that were indeed true, Heaven have mercy on us!” exclaimed he, piously. “Old Frederick will have but little pity for good Catholics! But no, Master Frank, this cannot be. The last time I received soldiers from Nuremberg they wore the same uniforms as ever, and the ‘Moriamur pro Rege nostro, M. T.’ was in gold letters on every banner as before.”

Frank was in no humor to disturb so innocent and so pleasing a delusion, and he gave no further opposition; and now they both descended the path which led to the little inn of the village. Here Hans insisted on performing the part of host, and soon the table was covered with brown bread and hard eggs, and those great massive sausages which Germans love, together with various flasks of Margrafler and other “Badisch” wines.

“Who knows,” said Hans, as he pledged his guest by ringing his wine-glass against the other’s, “if, when we meet again, thou wouldst sit down at the table with such as me?”

“How so, Hanserl?” asked the boy, in astonishment.

“I mean, Master Franz, that you may become a colonel, or perhaps a general, with, mayhap, the ‘St. Joseph’ at your button-hole, or the ‘Maria Teresa’ around your neck; and if so, how could you take your place at the board with the poor toy-maker?”

“I am not ashamed to do so now,” said Frank, haughtily; “and the Emperor cannot make me more a gentleman than my birth has done. Were I to be ashamed of those who befriended me, I should both disgrace my rank and name together.”

“These are good words, albeit too proud ones,” said Hans, thoughtfully. “As a guide through life, pride will do well enough when the roads are good and your equipage costly; but when you come upon mountain-paths and stony tracts, with many a wild torrent to cross, and many a dark glen to traverse, humility even a child’s humility will give better teaching.”

“I have no right to be other than humble!” said the boy; but the flashing brightness of his eyes, and the heightened color of his cheek, seemed to contradict his words.

For a while the conversation flagged, or was maintained in short and broken sentences, when at length Frank said,

“You will often go to see them, Hanserl, won’t you? You’ll sit with them, too, of an evening? for they will feel lonely now; and my father will like to tell you his stories about home, as he calls it still.”

“That will I,” said Hans; “they are the happiest hours of my life when I sit beside that hearth.”

Frank drew his hand across his eyes, and his lips quivered as he tried to speak.

“You’ll be kind to poor Ellen, too; she is so timid, Hans. You cannot believe how anxious she is, lest her little carvings should be thought unworthy of praise.”

“They are gems! they are treasures of art!” cried Hans, enthusiastically.

“And my sweet Kate!” cried the boy, as his eyes ran over, while a throng of emotions seemed to stop his utterance.

“She is so beautiful!” exclaimed Hans, fervently. “Except the Blessed Maria at the Holy Cross, I never beheld such loveliness. There is the Angelus ringing; let us pray a blessing on them;” and they both knelt down in deep devotion. Frank’s lips never moved, but with swelling heart and clasped hands he remained fixed as a statue; while Hanserl in some quaint old rhyme uttered his devotions.

“And yonder is the dog-star, bright and splendid,” said Hans, as he arose. “There never was a happier omen for the beginning of a journey. You ‘ll be lucky, boy; there is the earnest of good fortune. That same star was shining along the path as I entered Baden, eighteen years ago; and see what a lucky life has mine been!”

Frank could not but smile at the poor dwarf’s appreciation of his fortune; but Hanserl’s features wore a look that betokened a happy and contented nature.

“And yours has been a lucky life, Hanserl?” said he, half in question.

“Lucky? ay, that has it. I was a poor boy, barefooted and hungry in my native forest deformed, and stunted, too a thing to pity too weak to work, and with none to teach me, and yet even I was not forgotten by Him who made the world so fair and beautiful; but in my heart was planted a desire to be something to do something, that others might benefit by. The children used to mock me as I passed along the road; but a voice whispered within me, ‘Be of courage, Hanserl, they will bless thee yet, they will greet thee with many a merry laugh and joyous cry, and call thee their own kind Hanserl:’ and so have I lived to see it! My name is far and wide over Germany. Little boys and girls know and speak of me amongst the first words they syllable; and from the palace to the bauer’s hut, Hans Roeckle has his friends; and who knows that when this poor clay is mingled with the earth, but that my spirit will hover around the Christmas-tree when glad voices call upon me! I often think it will be so.”

Frank’s eyes glistened as he gazed upon the dwarf, who spoke with a degree of emotion and feeling very different from his wont.

“So you see, Master Franz,” said he, smiling, “there are ambitions of every hue, and this of mine you may deem of the very faintest, but it is enough for me. Had I been a great painter, or a poet, I would have revelled in the thought that my genius adorned the walls of many a noble palace, and that my verses kindled emotions in many a heart that felt like my own; but as one whom nature has not gifted, poor, ignoble, and unlettered, am I not lucky to have found a little world of joyous hearts and merry voices, who care for me % and speak of me, ay, and who would give me a higher place in their esteem than to Jean Paul, or Goethe himself?”

The friends had but time to pledge each other in a parting glass, when the stage drove up by which Hans was to return to Baden. A few hurried words, half cheering, half sorrowful, a close embrace, one long and lingering squeeze of the hand,

“Farewell, kind Hanserl!”

“God guide thee, Franz!” and they parted.

Frank stood in the little “Platz,” where the crowd yet lingered, watching the retiring “Post,” uncertain which, way to turn him. He dreaded to find himself all alone, and yet he shrank from new companionship. The newly risen moon and the calm air invited him to pursue his road; so he set out once more, the very exercise being a relief against his sad thoughts.

Few words are more easily spoken than “He went to seek his fortune;” and what a whole world lies within the narrow compass! A world of high-hearted hopes and doubting fear, of noble ambition to be won, and glorious paths to be trod, mingled with tender thoughts of home and those who made it such. What sustaining courage must be his who dares this course and braves that terrible conflict the toughest that ever man fought between his own bright coloring of life and the stern reality of the world! How many hopes has he to abandon, how many illusions to give up! How often is his faith to be falsified and his trustfulness betrayed; and, worst of all, what a fatal change do these trials impress upon himself, how different is he from what he had been!

Young and untried as Frank Dalton was in life, he was not altogether unprepared for the vicissitudes that awaited him; his sister Nelly’s teachings had done much to temper the over-buoyant spirit of his nature, and make him feel that he must draw upon that same courage to sustain the present, rather than to gild the future.

His heart was sorrowful, too, at leaving a home where unitedly they had, perhaps, borne up better against poverty. He felt for his own heart revealed it how much can be endured in companionship, and how the burden of misfortune like every other load is light when many bear it. Now thinking of these things, now fancying the kind of life that might lie before him, he marched along. Then he wondered whether the Count would resemble his father. The Daltons were remarkable for strong traits of family likeness, not alone in feature, but in character; and what a comfort Frank felt in fancying that the old general would be a thorough Dalton in frankness and kindliness of nature, easy in disposition, with all the careless freedom of his own father! How he should love him, as one of themselves!

It is a well-known fact, that certain families are remarkable above others for the importance that they attach to the ties of kindred, making the boast of relationship always superior to the claims of self-formed friendships. This is perhaps more peculiarly the case among those who live little in the world, and whose daily sayings and doings are chiefly confined to the narrow circle of home. But yet it is singular how long this prejudice for perhaps it deserves no better name can stand the conflict of actual life. The Daltons were a special instance of what we mean. Certain characteristics of look and feature distinguished them all, and they all agreed in maintaining the claim of relationship as the strongest bond of union; and it was strange into how many minor channels this stream meandered. Every old ruin, every monument, every fragment of armor, or ancient volume associated with their name, assumed a kind of religious value in their eyes, and the word Dalton was a talisman to exalt the veriest trifle into the rank of relic. From his earliest infancy Frank had been taught these lessons. They were the traditions of the parlor and the kitchen, and by the mere force of repetition became a part of his very nature. Corrig-O’Neal was the theme of every story. The ancient house of the family, and which, although by time’s changes it had fallen into the hands of the Godfreys from whom his mother came was yet regarded with all the feelings of ancient pride. Over and over again was he told of the once princely state that his ancestors held there, the troops of retainers, the mounted followers that ever accompanied them. The old house itself was exalted to the rank of a palace, and its wide-spreading but neglected grounds spoken of like the park of royalty.

To see this old house of his fathers, to behold with his own eyes the seat of their once greatness, became the passion of the boy’s heart. Never did the Bedouin of the Desert long after Mecca with more heart-straining desire. To such a pitch had this passion gained on him, that, unable any longer to resist an impulse that neither left his thoughts by day nor his dreams by night, he fled from his school at Bruges, and when only ten years old made his way to Ostend, and under pretence of seeking a return to his family, persuaded the skipper of a trading-vessel to give him a passage to Limerick. It would take us too far from our road already a long one were we to follow his wanderings and tell of all the difficulties that beset the little fellow on his lonely journey. Enough that we say, he did at last reach the goal, of his hopes, and, after a journey of eight long days, find himself at the ancient gate of Corrig-O’Neal.