The Project Gutenberg EBook of Tom Burke Of "Ours", Volume II (of II), by Charles James Lever This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Tom Burke Of "Ours", Volume II (of II) Author: Charles James Lever Illustrator: Phiz. Release Date: April 6, 2010 [EBook #31902] Last Updated: September 2, 2016 Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TOM BURKE II *** Produced by David Widger

Transcriber’s Note: Two print editions have been used for this Project Gutenberg Edition of “Tom Burke of ‘Ours’”: The Little Brown edition (Boston) of 1913 with illustrations by Phiz; and the Chapman and Hall editon (London) of 1853 with illustrations by Browne. Illegible and missing pages were found in both print editions.

DW

| VOLUME ONE |

CONTENTS

TOM BURKE OF “OURS"

CHAPTER I. THE SICK LEAVE

CHAPTER II. LINTZ

CHAPTER III. AUSTERLITZ

CHAPTER IV. THE FIELD AT MIDNIGHT

CHAPTER V. A MAÎTRE D’ARMES

CHAPTER VI. THE MILL ON THE HOLITSCH ROAD

CHAPTER VII. THE ARMISTICE

CHAPTER VIII. THE COMPAGNIE D’ELITE

CHAPTER IX. PARIS IN 1800

CHAPTER X. THE HÔTEL DE CLICHY

CHAPTER XI. A SALLE DE POLICE

CHAPTER XII. THE RETURN OF THE WOUNDED

CHAPTER XIII. THE CHEVALIER

CHAPTER XIV. A BOYISH REMINISCENCE

CHAPTER XV. A GOOD-BY

CHAPTER XVI. AN OLD FRIEND UNCHANGED

CHAPTER XVII. THE RUE DES CAPUCINES

CHAPTER XVIII. THE MOISSON d’OR

CHAPTER XIX. THE TWO SOIREES

CHAPTER XX. A SUDDEN DEPARTURE

CHAPTER XXI. THE SUMMIT OF THE LANDGRAFENBERG

CHAPTER XXII. L’HOMME ROUGE

CHAPTER XXII. JENA AND AUERSTÄDT

CHAPTER XXIV. A FRAGMENT OF A MAÎTRE d’ARMES EXPERIENCES

CHAPTER XXV. BERLIN AFTER “JENA.”

CHAPTER XXVI. A FOREST PATH

CHAPTER XXVII. A CHANCE MEETING

CHAPTER XXVIII. THE PENSION DE LA RUE MI-CARÊME

CHAPTER XXIX. MY NAMESAKE

CHAPTER XXX. AN OLD SAILOR OF THE EMPIRE

CHAPTER XXXI. A MOONLIGHT RECOGNITION

CHAPTER XXXII. THE FALAISE DE BIVILLE

CHAPTER XXXIII. THE LANDING

CHAPTER XXXIV. A CHARACTER OF OLD DUBLIN

CHAPTER XXXV. AN UNFORSEEN EVIL

CHAPTER XXXVI. THE PERIL AVERTED

CHAPTER XXXVII. HASTY RESOLUTION

CHAPTER XXXVIII. THE LAST CAMPAIGN

CHAPTER XXXIX. THE BRIDGE OF MONTEREAU

CHAPTER XL. FONTAINEBLEAU

CHAPTER XLI. THE CONCLUSION

A PARTING WORD.

ILLUSTRATIONS

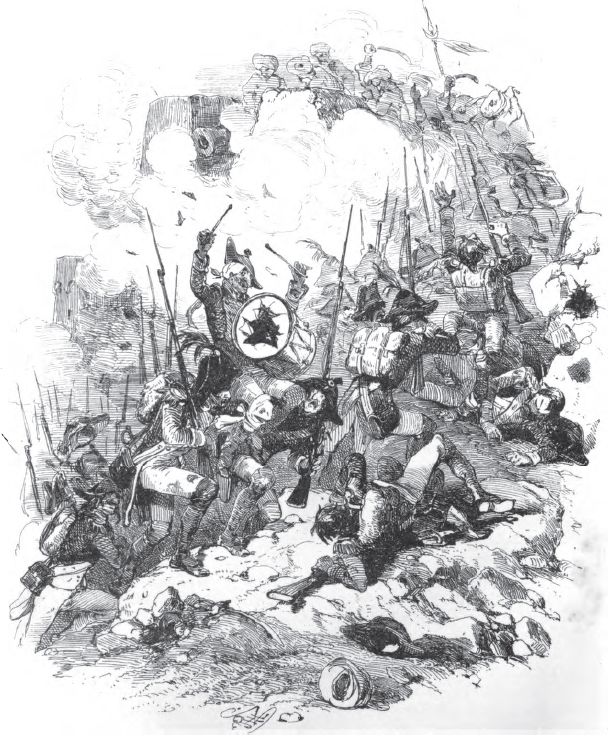

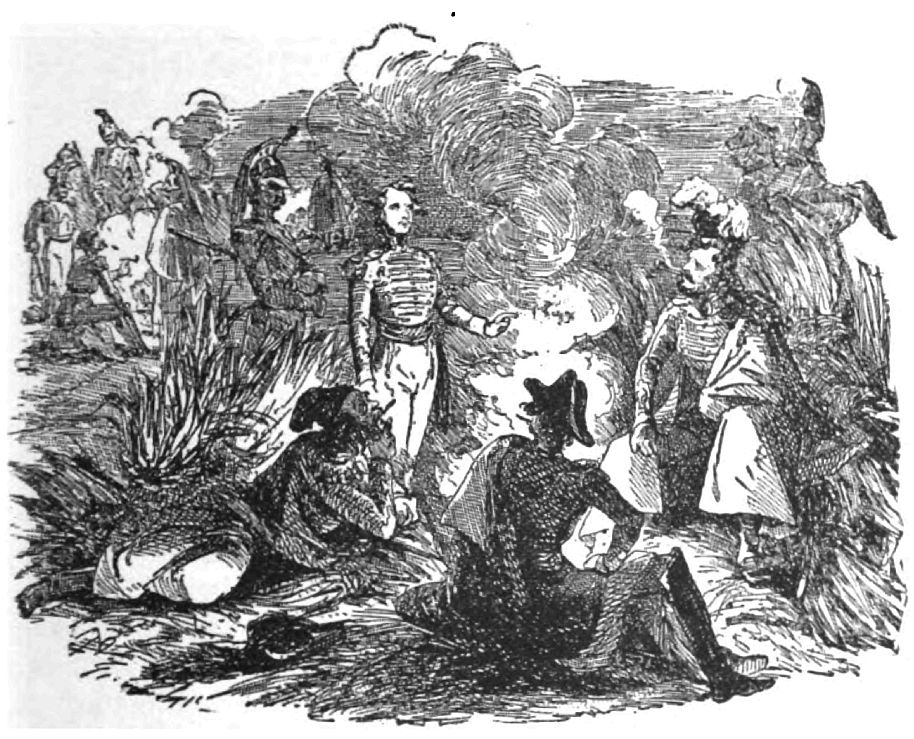

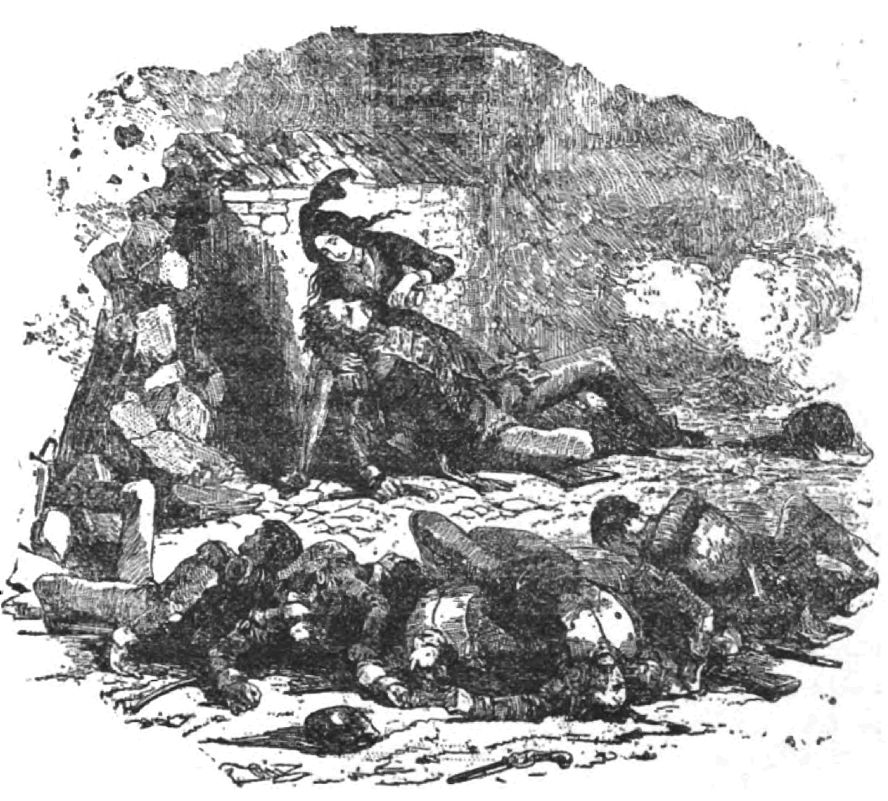

Browne: Bivwac After the Battle

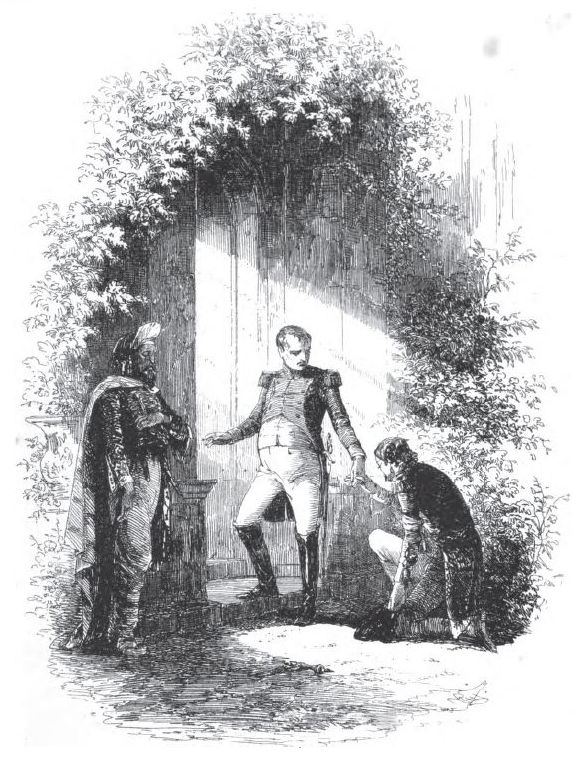

Phiz: Minnette Receives Cross of the Legion

Browne: Minnette Receives Cross of the Legion

“What is it, Minette?” said I, for the third time, as I saw her lean her head from out the narrow casement, and look down into the valley beside the river; “what do you see there?”

“I see a regiment of infantry coming along the road from Ulm,” said she, after a pause; “and now I perceive the lancers are following them, and the artillery too. Ah! and farther again, I see a great cloud of dust. Mère de Ciél! how tired and weary they all look! It surely cannot be a march in retreat; and, now that I think of it, they have no baggage, nor any wagons with them.”

“That was a bugle call, Minette! Did you not hear it?”

“Yes, it’s a halt for a few minutes. Poor fellows! they are sadly exhausted; they cannot even reach the side of the way, but are lying down on the very road. I can bear it no longer. I must find out what it all means.” So saying, she threw round her a mantle which, Spanish fashion, she wore over her head, and hurried from the room.

For some time I waited patiently for her return; but when half an hour elapsed, I arose and crept to the window. A succession of rocky precipices descended from the terrace on which the house stood, down to the very edge of the Danube, and from the point where I sat the view extended for miles in every direction. What, then, was my astonishment to see the wide plain, not marked by regular columns in marching array, but covered with straggling detachments, hurrying onward as if without order or discipline. Here was an infantry battalion mixed up with a cavalry corps, the foot-soldiers endeavoring to keep up with the ambling trot of the dragoons; there, the ammunition wagons were covered with weary soldiers, too tired to march. Most of the men were without their firelocks, which were piled in a confused heap on the limbers of the guns. No merry chant, no burst of warlike music, cheered them on. They seemed like the scattered fragments of a routed army hurrying onward in search of some place of refuge,-sad and spiritless.

“Can he have been beaten?” was the fearful thought that flashed across me as I gazed. “Have the bold legions that were never vanquished succumbed at last? Oh, no, no! I’ll not believe it.” And while a glow of fever warmed my whole blood, I buckled on my sabre, and taking my shako, prepared to issue forth. Scarcely had I reached the door, with tottering limbs, when I saw Minette dashing up the steep street at the top speed of her pony, while she flourished above her head a great placard, and waved it to and fro.

“The news! the news!” cried I, bursting with anxiety. “Are they advancing; or is it a retreat?”

“Read that!” said she, throwing me a large sheet of paper, headed with the words, “Proclamation! la Grande Armée!” in huge letters,-“read that! for I’ve no breath left to tell you.”

Soldiers!—The campaign so gloriously begun will soon be completed.

One victory, and the Austrian empire, so great but a week since, will be humbled in the dust. Hasten on, then! Forced marches, by day and night, will attest your eagerness to meet the enemy; and let the endeavor of each regiment be to arrive soonest on the field of battle.

“Minette! dearest Minette!” said I, as I threw my arms around her neck, “this is indeed good news.” “Gently, gently, Monsieur!” said she, smiling, while she disengaged herself from my sudden embrace. “Very good news, without doubt; but I don’t think that there is any mention in the bulletin about embracing the vivandières of the army.”

“At a moment like this, Minette—”

“The best thing to do is, to make up one’s baggage and join the march,” said she, very steadily, proceeding at the same time to put her plan into execution.

While I gave her all assistance in my power, the doctor entered to inform us that all the wounded who were then not sufficiently restored to return to duty were to be conveyed to Munich, where general military hospitals had been established; and that he himself had received orders to repair thither with his sick detachment, in which my name was enrolled.

“You’ll keep your old friend, François, company, Lieutenant Burke; he is able to move at last.”

“François!” said I, in ecstasy; “and will he indeed recover?”

“I have little doubt of it; though certainly he’s not likely to practise as maître d’armes again. You ‘ve spoiled his tierce, though not before it cost the army some of the prettiest fellows I ever saw. But as to yourself—”

“As for me, I ‘ll march with the army. I feel perfectly recovered; my arm—”

“Oh! as for monsieur’s arms,” said mademoiselle, “I’ll answer for it, they are quite at his Majesty’s service.”

“Indeed!” said the doctor, knowingly; “I thought it would come to that. Well, well, Mademoiselle, don’t look saucy; let us part good friends for once in our lives.”

“I hate being reconciled to a surgeon,” said she, pettishly.

“Why so, I pray?”

“Oh, you know, when one quarrels with an officer, the poor fellow may be killed before one sees him again; and it’s always a sad thought, that. But your doctor, nothing ever happens to him; you’re sure to see him, with his white apron and his horrid weapons, a hundred times after, and one is always sorry for having forgiven such a cruel wretch.”

“Come, come, Mademoiselle, you bear us all an ill-will for the fault of one, and that’s not fair. It was the hospital aide of the Sixth, Monsieur, (a handsome fellow, too), who did not fall in love with her after her wound,—a slight scratch.”

“A slight scratch, do you call it?” said I, indignantly, as I perceived the poor girl’s eyes fill at the raillery of her tormentor.

“Ah! monsieur has seen it, then?” said he, maliciously. “A thousand pardons. I have the honor to wish you both adieu.” And with that, and a smile of the most impertinent meaning, he took his leave.

“How silly to be vexed for so little, Minette!” said I, approaching and endeavoring to console her.

“Well, but to call my wound a scratch!” said she. “Was it not too bad? and I the only vivandière of the army that ever felt a bullet.”

And with that she turned away her head; but I could see, as she wiped her eyes, that she cared less for the sarcasm on her wounded shoulder than the insult to her wounded heart. Poor girl! she looked sick and pale the whole day after.

We learned in the course of the day that some cavalry detachments would pass early on the morrow, thus allowing us sufficient time to provide ourselves with horses, and make our other arrangements for the march. These we succeeded in doing to our satisfaction; I being fortunate enough to secure the charger of an Austrian prisoner, mademoiselle being already admirably mounted with her palfrey. Occupied with these details, the day passed rapidly over, and the hour for supper drew near without my feeling how the time slipped past.

At last the welcome meal made its appearance, and with it mademoiselle herself. I could not help remarking that her toilette displayed a more than common attention: her neat Parisian cap; her collar, with its deep Valenciennes lace; and her tablier, so coquettishly embroidered,—were all signs of an unusual degree of care; and though she was pale and in low spirits, I never saw her look so pretty. All my efforts to make her converse were, however, in vain. Some secret weight lay heavily on her spirits, and not even the stirring topics of the coming campaign could awaken one spark of her enthusiasm. She evaded, too, every allusion to the following day’s march, or answered my questions about it with evident constraint. Tired at last with endeavoring to overcome her silent mood, I affected an air of chagrin, thinking to pique her by it; but she merely remarked that I appeared weary, and that, as I had a long journey before me, it were as well I should retire early.

The marked coolness of her manner at this moment struck me so forcibly that I began really to feel some portion of the ill-temper I affected, and with the crossness of an over-petted child, I arose to withdraw at once.

“Good-by, Monsieur; good-night, I mean,” said she, blushing slightly.

“Good-night, Mademoiselle,” said I, taking her hand coldly as I spoke. “I trust I may find you in better spirits to-morrow.”

“Good-night,—adieu!” said she, hastily; and before I could add a word she was gone.

“She is a strange girl,” thought I, as I found myself alone, and tortured my mind to think whether anything I could have dropped had offended her. But no: we had parted a few hours before the best friends in the world; nothing had then occurred to which I could attribute this sudden change. I had often remarked the variable character of her disposition,—the flashes of gayety mingled with outbursts of sorrow; the playful moods of fancy alternating with moments of deep melancholy; and, after all, this might be one of them.

With these thoughts I threw myself on my bed, but could not sleep. At one minute my brain went on puzzling about Minette and her sorrow; at the next I reproached myself for my own harsh, unfeeling manner to the poor girl, and was actually on the eve of arising to seek her and ask her pardon. At last sleep came, and dreams too; but, strange enough, they were of the distant land of my boyhood and the hours of my youth; of the old house in which I was born, and its well-remembered rooms. I thought I was standing before my father, while he scolded me for some youthful transgression; I heard his words as though they were really spoken, as he told me that I should be an outcast and a wanderer, without a friend, a house, or home; that while others reaped wealth and honors, I was destined to be a castaway: and in the torrent of my grief I awoke.

It was night,—dark, silent night. A few stars were shining in the sky, but the earth was wrapped in shadow; and as I opened my window to let the fresh breeze calm my fevered forehead, the deep precipice beneath me seemed a vast gulf of yawning blackness. At a great distance off I could see the watchfires of some soldiers bivouacking in the plain; and even that much comforted my saddened heart, as it aroused me to the thoughts of the campaign before me. But again my thoughts recurred to my dream, which I could not help feeling as a sort of prediction.

When our sleep leaves its strong track in our waking moments, we dread to sleep again for fear the whole vision should come back; and thus I sat down beside the window, and fell into a long train of thought. The images of my dream were uppermost in my mind; and every little incident of childhood, long lost to memory, came now fresh before me,—the sorrows of my schoolboy years, unrelieved by the sense of love awaiting me at home; the clinging to all who seemed to feel or care for me; and the heart-sickening sorrow when I found that what I mistook for affection was merely pity: all save one,—my mother! Her mild, sad looks, so seldom cheered by a ray of pleasure,—I remember well how they fell on me! with such a thrilling sensation at my heart, and such a gush of thankfulness, as I felt then! Oh! if they who live with children knew how needful it is to open their hearts to all the little sorrows and woes of infant life; to teach confidence and to feed hope; to train up the creeping tendrils of young desire, and not to suffer them to lie straggling and tangled on the earth,—what a happier destiny would fall to the lot of many whose misfortunes in late life date from the crushed spirit of childhood!

My mother I—I thought of her as she would bend oyer me at night, her last kiss pressed on my brow,—the healing balm of some sorrow for which my sobs were still breaking,—her pale, worn cheek, her white dress, her hand so bloodless and transparent, the very emblem of her malady. The tears started to my eyes and rolled heavily along my cheek, my chest heaved, and my heart beat till I could hear it. At this moment a slight rustle stirred the leaves: I listened, for the night was calm and still; not a breeze moved. Again I heard it close beside the window, on the little terrace which ran along the building, and occupied the narrow space beside the edge of the rock. Before I could imagine what it meant, a figure in white glided from the shade of the trees and approached the window. So excited was my mind, so wrought up my imagination by the circumstances of my dream and the thoughts that followed, that I cried out, in a voice of ecstasy, “My mother!” Suddenly the apparition stood still, and then as rapidly retreated, and was lost to view in the dark foliage. Maddened with intense excitement, I sprang from the window, and leaped out on the terrace. I called aloud; I ran about wildly, unmindful of the fearful precipice that yawned beside me. I searched every bush, I crept beneath each tree, but nothing could I detect. The cold perspiration poured down my face; my limbs trembled with a strange dread of I knew not what. I felt as if madness was creeping over me, and I struggled with the thought and tried to calm my troubled brain. Wearied and faint, I gave up the pursuit at last, and, throwing myself on my bed, I sank exhausted into the heavy slumber which only tired nature knows.

“The Sous-Lieutenant Burke,” said a gruff voice, awakening me suddenly from my sleep, while by the light of a lantern he held in his hand I recognized the figure of an orderly sergeant in full equipment.

“Yes. What then?” said I, in some amazement at the summons.

“This is the order of march, sir, for the invalid detachment under your command.”

“How so? I have no orders.”

“They are here, sir.”

So saying, he presented me with a letter from the assistant-adjutant of the corps, with instructions for the conduct of forty men, invalided from different regiments, and now on their way to Lintz. The paper was perfectly regular, setting forth the names of the soldiers and their several corps, together with the daily marches, the halts, and distances. My only surprise was how this service so suddenly devolved on me, whose recovery could only have been reported a few hours before.

“When shall I muster the detachment, sir?” said the sergeant, interrupting me in the midst of my speculations.

“Now,—at once. It is past five o’clock. I see Langenau is mentioned as the first halting-place; we can reach it by eight.”

The moment the sergeant withdrew, I arose and dressed for the road, anxious to inform mademoiselle as early as possible of this sudden order of march. When I entered the salon, I found to my surprise that the breakfast table was all laid and everything ready. “What can this mean?” said I; “has she heard it already?” At the same instant I caught sight of the door of her chamber lying wide open. I approached, and looked in. The room was empty; the various trunks and boxes, the little relics of military glory I remembered to have seen with her, were all gone. Minette had departed; when or whither, I knew not. I hurried through the building, from room to room, without meeting any one. The door was open, and I passed out into the dark street, where all was still and silent as the grave. I hastened to the stable: my horse, ready equipped and saddled, was feeding; but the stall beside him was empty,—the pony of the vivandière was gone. While many a thought flashed on my brain as to her fate, I tortured my mind to remember each circumstance of our last meeting,—every word and every look; and as I called to my memory the pettish anger of my manner towards her, I grew sick at heart, and hated myself for my own cold ingratitude. All her little acts of kindness, her tender care, her unwearying good-nature, were before me. I thought of her as I had seen her often in the silence of the night, when, waking from some sleep of pain, she sat beside my bed, her hand pressed on my heated forehead; her low, clear voice was in my ear; her soft, mild look, beaming with hope and tender pity. Poor Minette! had I then offended you? was such the return I made for all your kindness?

“The men are ready, sir,” said the sergeant, entering at the moment.

“She is gone,” said I, following out my own sad train of thought, and pointing to the vacant stall where her pony used to stand.

“Mademoiselle Minette—”

“Yes, what of her—where is she?”

“Marched with the cuirassier brigade that passed here last night at twelve o’clock. She seemed very ill, sir, and the officer made her sit on one of the wagons.”

“Which road did they take? »

“They crossed the river, and moved away towards the forest. I think I heard the troop-sergeant say something about Salzburg and the Tyrol.”

I made no answer, but stood mute and stupefied; when I was again recalled to thought by his asking if my baggage was ready for the wagons.

With a sullen apathy I pointed out my trunks in silence, and throwing one last look on the room, the scene of my former suffering, and of much pleasure too, I mounted my horse, and gave the word to move forward.

As we passed from the gate, I stopped to question the sous-officier as to the route of the cuirassier division. But he could only repeat what the sergeant had already told me; adding, there were several men slightly wounded in the squadrons, for they had been engaged twice within the week. The gates closed! and we were on the highroad.

As day was breaking, we came up with a strong detachment of the cavalry of the Guard proceeding to join Bessiere’s division at Lintz. From them we learned that the main body of the army was already far in advance, several entire corps having marched from Lintz with the supposed intention of occupying Vienna. Ney’s division, it was said, was also bearing down from the Tyrol; Davoust and Mortier were advancing by the left bank of the Danube; whilst Lannes and Murat, with an overwhelming force of light troops, had pushed forward two days’ march in advance on their way to the capital. The fate of Ulm was already predicted for the Austrian city, and each day’s intelligence seemed to make it only the more inevitable. Meanwhile the Emperor Francis had abandoned the capital, and retreated on Brunn, a fortified town in Moravia, there to await the arrival of his ally, Alexander, hourly expected from Berlin.

As day after day we pressed forward, our numbers continued to increase. A motley force, indeed, did we present: cavalry of every sort, from the steel-clad cuirassier to the gay hussar, dragoons, chasseurs, guides, and light cavalry, all mixed up together, and all eagerly recounting the several experiences of the campaign as it fell under their eyes in different quarters. From none, however, could I learn any tidings of Minette; for though known to many there, the detachment she had joined had taken a southerly direction, and was not crossed by any of the others on their march. The General d’Auvergne, I heard, was with the headquarters of the Emperor, then established at the monastery of Molk, on the Danube.

On the evening of the 13th of November we arrived at Lintz, the capital of Upper Austria, but at the time I speak of one vast barrack. Thirty-eight thousand troops of all arms were within its walls; not subject to the rigid discipline and regular command of a garrison town, but bivouacking in the open streets and squares. Tables were spread in the thoroughfares, at which the divisions as they arrived took their places, and after refreshing themselves, moved on to make way for others. The great churches were strewn with forage, and filled with the horses of the cavalry; there might be seen the lumbering steeds of the cuirassier, eating their corn from the richly-carved box of a confessional; here lay the travel-stained figure of a dragoon, stretched asleep across the steps of the altar. The little chapelries, where the foot of the penitent awoke no echo as it passed, now rung with the coarse jest and reckless ribaldry of the soldiers; parties caroused in the little sacristies; and the rude chorus of a drinking song now vibrated through the groined roof where only the sacred notes of the organ had been heard to peal. The Hôtel de Ville was the quartier-général, where the generals of divisions were assembled, and from which the orderlies rode forth at every moment with despatches. The one cry, “Forward!” was heard everywhere. They who before had claimed leave for slight wounds or illness, were now seen among their comrades with bandaged arms and patched faces, eager to press on. Many whose regiments were in advance became incorporated for the time with other corps; and dismounted dragoons were often to be met with, marching with the infantry and mounting guard in turn. Everything bespoke haste. The regiments which arrived at night frequently moved off before day broke. The cavalry often were provided with fresh horses to press forward, leaving their own for the corps that were to follow. A great flotilla, provided with all the necessaries for an army on the march, moved along the Danube, and accompanied the troops each day. In a word, every expedient was practised which could hasten the movement of the army; justifying the remark so often repeated among the soldiers at the time, “Le Petit Caporal makes more use of our legs than our bayonets in this campaign.”

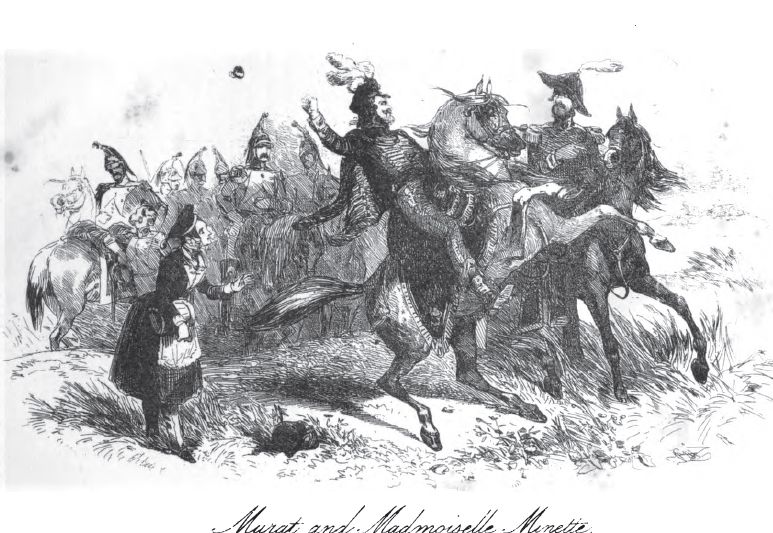

On the same evening we arrived came the news of the surprise of Vienna by Murat. Never was there such joy as this announcement spread through the army. The act itself was one of those daring feats which only such as he could venture on, and indeed at first seemed so miraculous that many refused to credit it. Prince Auersberg, to whom the great bridge of the Danube was intrusted, had prepared everything for its destruction in the event of attack. The whole line of woodwork was laid with combustibles; trains were set, the matches burning; a strong battery of twelve guns, posted to command the bridge, occupied the height on the right bank, and the Austrian gunners lay, match in hand, beside their pieces: but a word was needed, and the whole work was in a blaze.

Such was the state of matters when Sebastiani pushed through the faubourg of the Leopoldstadt at the head of a strong cavalry detachment, supported by some grenadiers of the Guard, and by Murat’s orders, concealed his force among the narrow streets which lead to the bridge from the left bank of the Danube. This done, Lannes and Murat advanced carelessly along the bridge, which, from the frequent passage of couriers between the two headquarters, had become a species of promenade, where the officers of either side met to converse on the fortunes of the campaign. Dressed simply as officers of the staff, they strolled along till they came actually beneath the Austrian battery; and then entered into conversation with the Austrian officers, assuring them that the armistice was signed, and peace already proclaimed between the two countries.

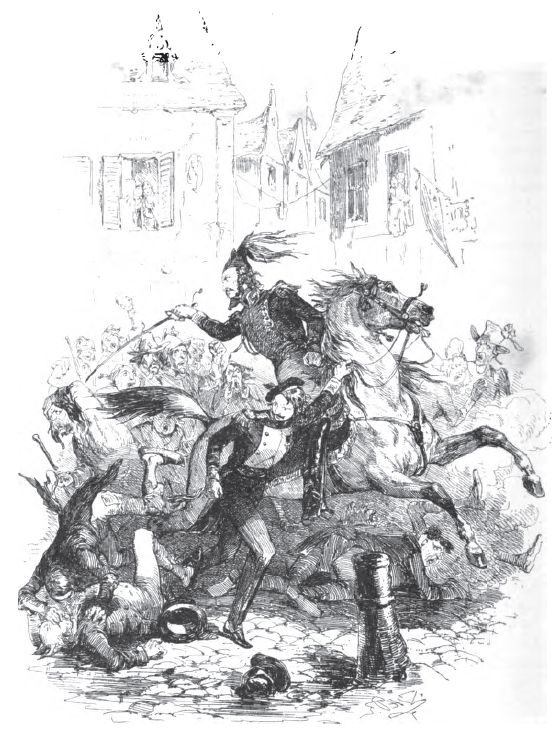

The Austrians, trusting to their story, and much interested by what they heard, descended from the mound, and joining them, proceeded to walk backwards and forwards along the bridge, conversing on the probable consequences of the treaty; when suddenly turning round by chance, as they walked towards the right bank, they saw the head of a grenadier column approaching at the quick step. The thought of treachery crossed their minds; and one of them, rushing to the side of the bridge, called out to the artillerymen to fire. A movement was seen in the battery, the matches were uplifted, when Murat, dashing forward, cried aloud, “Reserve your fire; there is nothing to fear!”

The same instant the Austrian officers were surrounded; the sappers rushing on the bridge cleared away the combustibles, and cut off the trains; and the cavalry, till now in concealment, pushing forward at a gallop, crossed the bridge, followed by the grenadiers in a run,—before the Austrians, who saw their own officers mingled with the French, could decide on what was to be done,—while Murat, springing on his horse, dashed forward at the head of the dragoons; and before five minutes elapsed the battery was stormed, the gunners captured, and Vienna won.

Never was there a coup de main more hardy than this, whether we look to the danger of the deed itself, or the insignificant force by which it was accomplished. A few horsemen and some companies of foot, led on by an heroic chief, thus turned the whole fortune of Europe; for, by securing this bridge, Napoleon enabled himself, as circumstances might warrant, to unite the different corps of his army on the right or left banks of the Danube, and either direct his operations against the Russians, or the Austrians under the Archduke Charles, as he pleased.

The treachery by which the bold deed was made successful, was, alas! deemed no stain on the achievement. But one rule of judgment existed in the Imperial army: Was the advantage on the side of France, and to the honor of her arms? That covered every flaw, no matter whether inflicted by duplicity or breach of faith. The habit of healing all wounds of conscience by a bulletin had become so general, that men would not trust to the guidance of their own reason till confirmed by some Imperial proclamation; and when the Emperor declared a battle gained and glory achieved, who would gainsay him? If this blind, headlong confidence tended to lower the morale of the nation, in an equal degree did it make them conquerors in the field; and thus—by a strange decree of Providence, would it seem—were they preparing for themselves the terrible reverse of fortune which, when the destinies of their leader became clouded and their confidence in him shaken, was to fall on a people who lived only in the mad intoxication of victory, and knew not the sterner virtues that can combat with defeat.

But so was it. Napoleon commanded the legions and described their achievements; he led them to the charge and he apportioned their glory; the heroism of the soldier had no existence until acknowledged by the proclamation after the battle; the valor of the general wanted confirmation till sealed by his approval. To fight beneath his eyes was the greatest glory a regiment could wish for; to win one word from him was fame itself forever.

If I dwell on these thoughts here, it is because I now felt for the first time the sad deception I had practised on myself; and how little could I hope to realize in my soldier’s life the treasured aspirations of my boyhood Î Was this, then, indeed the career I had pictured to my mind,—the chivalrous path of honor? Was this the bold assertion of freedom I so often dreamed of? How few of that armed host knew anything of the causes of the war,—how much fewer still cared for them! No sentiment of patriotism, no devotion to the interests of liberty or humanity, prompted us on. Yet these were the thoughts first led me to the career of arms; such ambitious promptings first made my heart glow with the enthusiasm of a soldier.

This gloomy disappointment made me low-spirited and sad. Nor can I say where such reflections might not have led me, when suddenly a change came over my thoughts by seeing a wounded soldier, who had just arrived from Mortier’s division, with news of a fierce encounter they had sustained against Kutusof’s Russians. The poor fellow was carried past in a litter,—his arm had been amputated that same morning, and a frightful shot-wound had carried away part of his cheek; still, amid all his suffering, his eye was brilliant, and a smile of proud meaning was on his lips.

“Lift it up, Guillaume; let me see it again,” said he, as they bore him along the crowded street.

“What is it he wishes?” said I. “The poor fellow is asking for something.”

“Yes, mon lieutenant. It is the sabre d’honneur the Emperor gave him this morning. He likes to look at it every now and then; he says he doesn’t mind the pain when he sees that before him. And it is natural, too.”

“Such is glory!” said I to myself; “and he who feels this in his heart has no room for other thoughts.”

“Oh, give to me the trumpet’s blast, And the champ of the charger prancing; Or the whiz of the grape-shot flying past, That ‘a music meet for dancing.

“Tralararalal” sang a wild-looking voltigeur, as he capered along the street, keeping time to his rude song with the tramp of his feet.

“Ha! there goes a fellow from the Faubourg!” said an officer near me.

“The Faubourg?” repeated I, asking for explanation.

“Yes, to be sure. The Faubourg St. Antoine supplies all the reckless devils of the army; one of them would corrupt a regiment, and so, the best thing to do is to keep them as much together as possible. The voltigeurs have little else; and proof is, they are the cleverest corps in the service, and if they could be kept from picking and stealing, lying, drinking, and gambling, there’s not a man might not be a general of division in time. There goes another!”

As he spoke, a fellow passed by with a goose under his arm, followed by a woman most vociferously demanding restitution; while he only amused himself by replying with a mock courtesy, deploring in sad terms the unhappy necessities of war and the cruel hardships of a campaign.

“It’s no use punishing those fellows,” said the officer. “They desert in whole companies if you send one to the salle de police; and so we have only one resource, which is, to throw them pretty much in advance, and leave their chastisement to the enemy. And, sooth to say, they ask for nothing better themselves.”

Thus, even these fellows seemed to have their own sentiment of glory,—a problem which the more I reasoned over the more puzzled did I become.

While a hundred conjectures were hourly in circulation, none save those immediately about the person of Napoleon could possibly divine the quarter where the great blow was to be struck, although all were in expectation of the orders to prepare for battle. News would reach us of marchings and counter-marchings; of smart skirmishes here, and prisoners taken there; yet could we not form the slightest conception of where the chief force of the enemy lay, nor what the direction to which our own army was pointed. Indeed, our troops seemed to scatter on every side. Marmont, with a strong force, was despatched towards Gratz, where it was said the Archduke Charles was at the head of a considerable army; Davoust moved on Hungary, and occupied Presburg; Bernadotte retraced his steps towards the Upper Danube, to hold the Archduke Frederick in check, who had escaped from Ulm with ten thousand men; Mortiers corps, harassed and broken by the engagement with Kutusof, were barely sufficient to garrison Vienna; while Soult, Lannes, and Murat pushed forward towards Moravia, with a strong cavalry force and some battalions of the Guard. In fact, the whole army was scattered like an exploded shell; nor could we see the means by which its wide extended fragments were to be united at a moment, much less divine the spot to which their combined force was to be directed.

Had these Russians been fabulous creatures of a legend, instead of men of mortal mould, they could scarcely have been endowed with more attributes of ubiquity than we conferred on them. Sometimes we believed them at one side of the Danube, sometimes at the other; now we heard of them as retreating by forced marches into their native fastnesses, now as encamped in the mountain regions of Moravia. Yesterday came the news that they laid down their arms and surrendered as prisoners of war; to-day we heard of them as having forced back our advanced posts and carried off several squadrons as prisoners.

At length came the positive information that the allied armies were in cantonments around Olmutz; while Napoleon had pushed forward to Brunn, a place of considerable strength, communicating by the highroad with the Russian headquarters. It was no longer doubtful, then, where the great game was to be decided, and thither the various battalions were now directed by marches day and night.

On the 29th of November our united detachments, now numbering several hundred men, arrived at Brunn. I lost no time in repairing to headquarters, where I found General d’Auvergne deeply engaged with the details of the force under his command: his brigade had been placed under the orders of Murat; and it was well known the prince gave little rest or respite to those under his command. From him I learned that three days of unsuccessful negotiation had just passed over, and that the Emperor had now resolved on a great battle. Indeed, every moment was critical. Russia had assumed a decidedly hostile aspect; the Swedes were moving to the south; the Archduke Charles, by a circuitous route, was on the march to join the Russian army, to whose aid fresh reinforcements were daily arriving, and Benningsen was hourly expected with more. Under these circumstances a battle was inevitable; and such a one, as, by its result, must conclude the war.

This much did I learn from the old general as we rode over the field together; examining with caution the nature of the ground, and where it offered facilities, and where it presented obstacles, to the movement of cavalry. Such were the orders issued that morning by Napoleon to the generals of brigade, who might now be seen with their staffs traversing the plain in every direction. As we moved along we could discover in the distance the dark columns of the enemy marching, not towards us, but in a southerly direction towards our extreme right. This movement attracted the attention of several others, and more than one aide-de-camp was despatched to Brunn to carry the intelligence to the Emperor.

The same evening couriers departed in every direction to Bernadotte and Davoust to hasten forward at once; even Mortier, with his mangled division, was ordered to abandon Vienna to a division of Marmont’s army, and move on to Brunn. And now the great work of concentration began.

Meanwhile the Russians advanced, and on the 30th drove in an advanced post, and compelled our cavalry to fall back behind our position. The following morning the allies resumed their flank movement. And now no doubt could be entertained of their plan; which was, by turning our right, to cut us off from our supporting columns resting at Vienna, and throw our retreat back upon the mountainous districts of Bohemia. In this way five massive columns moved past us scarce half a league distant from our advanced posts, numbering eighty thousand men, of which fifteen were cavalry in the most perfect condition.

Our position was in advance of the fortress of Brunn; the headquarters of the Emperor occupied a rising piece of ground, at the base of which flowed a small stream, a tributary to some of the numerous ponds by which the field was intersected. The entire ground in our front was indeed a succession of these small lakes, with villages interspersed, and occasionally some stunted woods; great morasses extended around these ponds, through which led the highroads or such bypaths as conducted from one village to another. Here and there were plains where cavalry might act with safety, but rarely in large bodies.

Our right rested on the lake of Moeritz, where Soult’s division was stationed; behind which, thrown back in such a manner as to escape the observation of the enemy, was Davoust’s corps, the reserve occupying a cliff of ground beside the convent of Eeygern. Our left, under Lannes, occupied the hill of Santon,—a wooded eminence, the last of a long chain of mountains running east and west. Above, and on the crest of the height, a powerful park of artillery was posted, and defended by strong intrenchments. A powerful cavalry corps was placed at the bottom of the mountain. Next came Bernadotte’s division, separated by the highroad from Brunn to Olmutz from the division under Murat, which, besides his own cavalry, contained Oudinot’s grenadiers and Bessière’s battalions of the Imperial Guard; the centre and right being formed of Soult’s division, the strongest of all; the reserve, consisting of several battalions of the Guard and a strong force of artillery, being under the immediate orders of Napoleon, to be employed wherever circumstances demanded.

These were the dispositions for the coming battle, made with all the precision of troops moving on parade; and such was the discipline of the army at Boulogne, and so perfectly arranged the plans of the Emperor, that the ground of every regiment was marked out, and each corps moved into its allotted space with the regularity of some piece of mechanism.

The dispositions for the battle of Austerlitz occupied the entire day. From sunrise Napoleon was on horse-back, visiting every position; he examined each battery with the skill of an old officer of artillery; and frequently dismounting from his horse, carefully noted the slightest peculiarities of the ground,—remarking to his staff, with an accuracy which the event showed to be prophetic, the nature of the struggle, as the various circumstances of the field indicated them to his practised mind.

It was already late when he turned his horse’s head towards the bivouac hut,—a rude shelter of straw,—and rode slowly through the midst of that great army. The ordre du jour, written at his own dictation, had just been distributed among the soldiers; and now around every watchfire the groups were kneeling to read the spirit-stirring lines by which he so well knew how to excite the enthusiasm of his followers. They were told that “the enemy were the same Russian battalions they had already beaten at Hollabrunn, and on whose flying traces they had been marching ever since.” “They will endeavor,” said the proclamation, “to turn our right, but in doing so they must open their flank to us: need I say what will be the result? Soldiers, so long as with your accustomed valor you deal death and destruction in their ranks, so long shall I remain beyond the reach of fire; but let the victory prove, even for a moment, doubtful, your Emperor shall be in the midst of you. This day must decide forever the honor of the infantry of France. Let no man leave his ranks to succor the wounded,—they shall be cared for by one who never forgets his soldiers,—and with this victory the campaign is ended!”

Never were lines better calculated to stimulate the energy and flatter the pride of those to whom they were addressed. It was a novel thing in a general to communicate to his army the plan of his intended battle, and perhaps to any other than a French army the disclosure would not have been rated as such a favor; but their warlike spirit and military intelligence have ever been most remarkably united, and the men were delighted with such a proof of confidence and esteem.

A dull roar, like the sound of the distant sea, swelled along the lines from the far right, where the Convent of Reygern stood, and growing louder by degrees, proclaimed that the Emperor was coming. It was already dark, but he was quickly recognized by the troops, and with one burst of enthusiasm they seized upon the straw of their bivouacs, and setting fire to it, held the blazing masses above their heads, waving them wildly to and fro, amid the cries of “Vive l’Empereur!” For above a league along the plain the red light flashed and glowed, marking out beneath it the dense squares and squadrons of armed warriors. It was the anniversary of Napoleon’s coronation; and such was the fête by which they celebrated the day.

The Emperor rode through the ranks uncovered. Never did a prouder smile light up his features, while thronging around him the veterans of the Guard struggled to catch even a passing glance at him. “Do but look at us tomorrow, and keep beyond the reach of shot,” said a grognard, stepping forward; “we’ll bring their cannon and their colors, and lay them at thy feet.” The marshals themselves, the hardened veterans of so many fights, could not restrain their enthusiasm; and proffers of devotion unto death accompanied him as he went.

At last all was silent in the encampment; the soldiers slept beside their watchfires, and save the tramp of a patrol or the qui vive? of the sentinels, all was still. The night was cold and sharp; a cutting wind blew across the plain, which gave way to a thick mist,—so thick, the sentries could scarcely see a dozen paces off.

I sat in my little hovel of straw,—my mind far too much excited for sleep,—watching the stars as they peeped out one by one, piercing the gray mist, until at last the air became thin and clear, and a frosty atmosphere succeeded to the weighty fog; and now I could trace out the vast columns, as they lay thickly strewn along the plain. The old general, wrapped in his cloak, slept soundly on his straw couch; his deep-drawn breathing showed that his rest was unbroken. How slowly did the time seem to creep along! I thought it must be nigh morning, and it was only a little more than midnight.

Our position was a small rising ground about a mile in front of the left centre, and communicating with the enemy’s line by a narrow road between the marshes. This had been defended by a battery of four guns, with a stockade in front; and along it now, for a considerable distance, a chain of sentinels were placed, who should communicate any movement that they observed in the Russian lines, of which I was charged to convey the earliest intelligence to the quartier-général. This duty alone would have kept me in a state of anxiety, had not the frame of my mind already so disposed me; and I could not avoid creeping out from time to time, to peer through the gloom in the direction of the enemy’s camp, and listen with an eager ear for any sounds from that quarter. At last I heard the sound of a voice at some distance off; then, a few minutes after, the hurried step of feet, and a voltigeur came up, breathless with haste: “The Russians were in motion towards the right. Our advanced posts could hear the roll of guns and tumbrels moving along the plain, and it was evident their columns were in march.” I knelt down and placed my ear to the ground, and almost started at the distinctness with which I could hear the dull sound of the large guns as they were dragged along; the earth seemed to tremble beneath them.

I awoke the general at once, who, resting on his arm, coolly heard my report; and having directed me to hasten to headquarters with the news, lay back again, and was asleep before I was in my saddle. At the top speed of my horse I galloped to the rear, winding my way between the battalions, till I came to a gentle rising ground, where, by the light of several large fires that blazed in a circle I could see the dismounted troopers of the chasseurs à cheval, who always formed the Imperial Bodyguard. Having given the word, I was desired by the officer of the watch to dismount, and following him, I passed forward to a space in the middle of the circle, where, under shelter of some sheaves of straw piled over each other, sat three officers, smoking beside a fire.

“Ha! here comes news of some sort,” said a voice I knew at once to be Murat’s. “Well, sir, what is’t?”

“The Russian columns are in motion, Monsieur le Maréchal; the artillery moving rapidly towards our right.”

“Diantre! it’s not much more than midnight! Davoust, shall we awake the Emperor?”

“No, no,” said a harsh voice, as a shrivelled, hard-featured man turned round from the blaze, and showing a head covered by a coarse woollen cap, looked far more like a pirate than a marshal of France; “they ‘ll not attack before day breaks. Go back,” said he, addressing me; “observe the position well, and if there be any general movement towards the southward, you may report it.”

By the time I regained my post, all was in silence once more; either the Russians had arrested their march, or already their columns were out of hearing,—not a gleam of light could I perceive along their entire position. And now, worn out with watching, I threw myself down among the straw, and slept soundly.

“There! there! that’s the third!” said General d’Auvergne, shaking me by the shoulder; “there again! Don’t you hear the guns?”

I listened, and could just distinguish the faint booming sound of far-off artillery coming up from the extreme right of our position. It was still but three o’clock, and although the sky was thick with stars, perfectly dark in the valley. Meanwhile we could bear the galloping of cavalry quite distinctly in the same direction.

“Mount, Burke, and back to the quartier-général! But you need not; here comes some of the staff.”

“So, D’Auvergne,” cried a voice whose tones were strange to me, “they meditate a night attack, it would seem; or is it only trying the range of their guns?”

“I think the latter, Monsieur le Maréchal, for I heard no small arms; and, even now, all is quiet again.”

“I believe you are right,” said he, moving slowly forward, while a number of officers followed at a little distance. “You see, D’Auvergne, how correctly the Emperor judged their intentions. The brunt of the battle will be about Reygern. But there! don’t you hear bugles in the valley?”

As he spoke, the music of our tirailleurs’ bugles arose from the glen in front of our centre, where, in a thick beech-wood, the light infantry regiments were posted.

“What is it, D’Esterre?” said he to an officer who galloped up at the moment.

“They say the Russian Guard, sir, is moving to the front; our skirmishers have orders to fall back without firing.”

As he heard this, the Marshal Bernadotte—for it was he—turned his horse suddenly round, and rode back, followed by his staff. And now the drums beat to quarters along the line, and the hoarse trumpets of the cavalry might be heard summoning the squadrons throughout the field; while between the squares, and in the intervals of the battalions, single horsemen galloped past with orders. Soult’s division, which extended for nearly a league to our right, was the first to move, and it seemed like one vast shadow creeping along the earth, as column beside column marched steadily onward. Our brigade had not as yet received orders, but the men were in readiness beside the horses, and only waiting for the word to mount.

The suspense of the moment was fearful. All that I had ever dreamed or pictured to myself of a soldier’s enthusiasm was faint and weak, compared to the rush of sensations I now experienced. There must be a magic power of ecstasy in the approach of danger,—some secret sense of bounding delight, mingled with the chances of a battle,—that renders one intoxicated with excitement. Each booming gun I heard sent a wild throb through me, and I panted for the word “Forward!”

Column after column moved past us, and disappeared in the dip of ground beneath; and as we saw the close battalions filling the wide plain in front, we sighed to think that it was destined to be the day of glory peculiarly to the infantry. Wherever the nature of the field permitted shelter or the woods afforded cover, our troops were sent immediately to occupy. The great manoeuvre of the day was to be the piercing of the enemy’s centre whenever he should weaken that point by the endeavor to turn our right flank.

A faint streak of gray light was marking the horizon when the single guns which we had heard at intervals ceased; and then, after a short pause, a long, loud roll of artillery issued from the distant right, followed by the crackling din of small-arms, which increased at every moment, and now swelled into an uninterrupted noise, through which the large guns pealed from time to time. A red glare, obscured now and then by means of black smoke, lit up the sky in that quarter, where already the battle was raging fiercely.

The narrow causeway between the two small lakes in our front conducted to an open space of ground, about a cannon-shot from the Russian line; and this we were now ordered to occupy, to be prepared to act as support to the infantry of Soult’s left, whenever the attack began. As we debouched into the plain, I beheld a group of horsemen, who, wrapped up in their cloaks, sat motionless in their saddles, calmly regarding the squadrons as they issued from the wood: these were Murat and his staff, to whom was committed the attack on the Russian Guard. His division consisted of the hussars and chasseurs under Kellermann, the cuirassiers of D’Auvergne, and the heavy dragoons of Nansouty,—making a force of eight thousand sabres, supported by twenty pieces of field artillery. Again were we ordered to dismount, for although the battle continued to rage on the right, the whole of the centre and left were unengaged.

Thus stood we as the sun arose,—that “Sun of Austerlitz!” so often appealed to and apostrophized by Napoleon as gilding the greatest of his glories. The mist from the lakes shut out the prospect of the enemy’s lines at first; but gradually this moved away, and we could perceive the dark columns of the Russians, as they moved rapidly along the side of the Pratzen, and continued to pour their thousands towards Reygern.

At last the roar of musketry swelled louder and nearer, and an officer galloping past told us that Soult’s right had been called up to support Davoust’s division. This did not look well; it proved the Russians had pressed our lines closely, and we waited impatiently to hear further intelligence. It was evident, too, that our right was suffering severely, otherwise the attack on the centre would not have been delayed. Just then a wild cheer to the front drew our attention thither, and we saw the heads of three immense columns—Soult’s division—advancing at a run towards the enemy.

“Par Saint Louis,” cried General d’Auvergne, as he directed his telescope on the Russian line, “those fellows have lost their senses! See if they have not moved their artillery away from the Pratzen, and weakened their centre more and more! Soult sees it: mark how he presses his columns on! There they go, faster and faster! But look! there’s a movement yonder,—the Russians perceive their mistake.”

“Mount!” was now heard from squadron to squadron; while dashing along the line like a thunderbolt, Murat rode far in advance of his staff, the men cheering him as he went.

“There!” cried D’Auvergne, as he pointed with his finger, “that column with the yellow shoulder-knots,—that’s Vandamme’s brigade of light infantry; see how they rush on, eager to be first up with the enemy. But St. Hilaire’s grenadiers have got the start of them, and are already at the foot of the hill. It is a race between them!”

And so had it become. The two columns advanced, cheering wildly; while the officers, waving their caps, led them on, and others rode along the flanks urging the men forward.

The order now came for our squadrons to form in charging sections, leaving spaces for the light artillery between. This done, we moved slowly forward at a walk, the guns keeping step by step beside us. A few minutes after, we lost sight of the attacking columns; but the crashing fire told us they were engaged, and that already the great struggle had begun.

For above an hour we remained thus; every stir, every word loud spoken, seeming to our impatience like the order to move. At last, the squadrons to our right were seen to advance; and then a tremulous motion of the whole line showed that the horses themselves participated in the eagerness of the moment; and, at last, the word came for the cuirassiers to move up. In less than a hundred yards we were halted again; and I heard an aide-de-camp telling General d’Auvergne that Davoust had suffered immensely on the right; that his division, although reinforced, had fallen back behind Reygern, and all now depended on the attack of Soult’s columns.

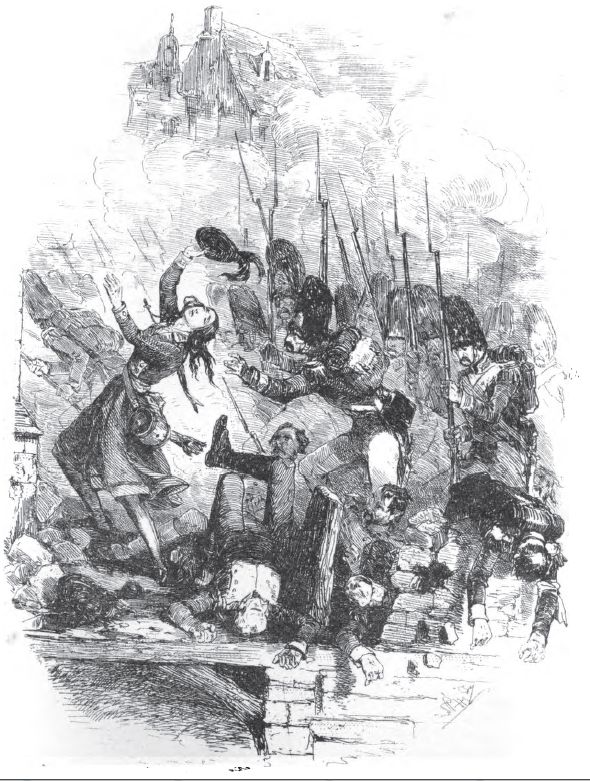

I heard no more, for now the whole line advanced in trot, and as our formation showed an unbroken front, the word came,—“Faster!” and “Faster!” As we emerged from the low ground we saw Soult’s column already half way up the ascent; they seemed like a great wedge driven into the enemy’s centre, which, opening as they advanced, presented two surfaces of fire to their attack.

“The battery yonder has opened its fire on our line,” said D’Auvergne; “we cannot remain where we are.”

“Forward!—charge!” came the word from front to rear, and squadron after squadron dashed madly up the ascent. The one word only, “Charge!” kept ringing through my head; all else was drowned in the terrible din of the advance. An Austrian brigade of light cavalry issued forth as we came up, but soon fell back under the overwhelming pressure of our force. And now we came down upon the squares of the red-brown Russian infantry. Volley after volley sent back our leading squadrons, wounded and repulsed, when, unlimbering with the speed of lightning, the horse artillery poured in a discharge of grapeshot. The ranks wavered, and through their cleft spaces of dead and dying our cuirassiers dashed in, sabring all before them. In vain the infantry tried to form again: successive discharges of grape, followed by cavalry attacks, broke through their firmest ranks; and at last retreating, they fell back under cover of a tremendous battery of field-guns, which, opening their fire, compelled us to retire into the wood.

Nor were we long inactive. Bernadotte’s division was now engaged on our left, and a pressing demand came for cavalry to support them. Again we mounted the hill, and came in sight of the Russian Guard, led on by the Grand-Duke Constantino himself,—a splendid body of men, conspicuous for their size and the splendor of their equipment. Such, however, was the impetuous torrent of our attack that they were broken in an instant; and notwithstanding their courage and devotion, fresh masses of our dragoons kept pouring down upon them, and they were sabred, almost to a man.

While we were thus engaged, the battle became general from left to right, and the earth shook beneath the thundering sounds of two hundred great guns. Our position, for a moment victorious, soon changed; for having followed the retreating squadrons too far, the waves closed behind us, and we now saw that a dense cloud of Austrian and Russian cavalry were forming in our rear. An instant of hesitation would have been fatal. It was then that a tall and splendidly-dressed horseman broke from the line, and with a cry to “Follow!” rode straight at the enemy. It was Murat himself, sabre in hand, who, clearing his way through the Russians, opened a path for us. A few minutes after we had gained the wood; but one third of our force had fallen.

“Cavalry! cavalry!” cried a field-officer, riding down at headlong speed, his face covered with blood from a sabre-cut, “to the front!”

The order was given to advance at a gallop; and we found ourselves next instant hand to hand with the Russian dragoons, who having swept along the flank of Bernadotte’s division, were sabring them on all sides. On we went, reinforced by Nansouty and his carabineers, a body of nigh seven thousand men. It was a torrent no force could stem. The tide of victory was with us; and we swept along, wave after wave, the infantry advancing in line for miles at either side, while whole brigades of artillery kept up a murderous fire without ceasing. Entire columns of the enemy surrendered as prisoners; guns were captured at each instant; and only by a miracle did the Grand-Duke escape our hussars, who followed him till he was lost to view in the flying ranks of the allies.

As we gained the crest of the hill, we were in time to see Soult’s victorious columns driving the enemy before them; while the Imperial Guard, up to that moment unengaged, reinforced the grenadiers on the right, and broke through the Russians on every side.

The attempt to outflank us on the right we had perfectly retorted on the left; where Lannes’s division, overlapping the line, pressed them on two sides, and drove them back, still fighting, into the plain, which, with a lake, separated the allied armies from the village of Austerlitz. And here took place the most dreadful occurrence of the day.

The two roads which led through the lake were soon so encumbered and blocked up by ammunition wagons and carts that they became impassable; and as the masses of the fugitives thickened, they spread over the lake, which happened to be frozen. It was at this time that the Emperor came up, and seeing the cavalry halted, and no longer in pursuit of the flying columns, ordered up twelve pieces of the artillery of the Imperial Guard, which, from the crest of the hill, opened a murderous fire on them. The slaughter was fearful as the discharges of grape and round shot cut channels through the jammed-up mass, and tore the dense columns, as it were, into fragments.

Dreadful as the scene was, what followed far exceeded it in horror; for soon the shells began to explode beneath the ice, which now, with a succession of reports louder than thunder, gave way. In an instant whole regiments were ingulfed, and amid the wildest cries of despair, thousands sank never to appear again, while the deafening artillery mercilessly played upon them, till over that broad surface no living thing was seen to move, while beneath was the sepulchre of five thousand men. About seven thousand reached Austerlitz by another road to the northward; but even these had not escaped, save for a mistake of Bernadotte, who most unaccountably, as it was said, halted his division on the heights. Had it not been for this, not a soldier of the Russian right wing had been saved.

The reserve cavalry and the dragoons of the Guard were now called up from the pursuit, and I saw my own regiment pass close by me, as I stood amid the staff round Murat. The men were fresh and eager for the fray; yet how many fell in that pursuit, even after the victory! The Russian batteries continued their fire to the last. The cannoneers were cut down beside their guns, and the cavalry made repeated charges on our advancing squadrons; nor was it till late in the day they fell back, leaving two thirds of their force dead or wounded on the field of battle.

On every side now were to be seen the flying columns of the allies, hotly followed by the victorious French. The guns still thundered at intervals; but the loud roar of battle was subdued to the crashing din of charging squadrons, and the distant cries of the vanquishers and the vanquished. Around and about lay the wounded in all the fearful attitudes of suffering; and as we were fully a league in advance of our original position, no succor had yet arrived for the poor fellows whose courage had carried them into the very squares of the enemy.

Most of the staff—myself among the number—were despatched to the rear for assistance. I remember, as I rode along at my fastest speed, between the columns of infantry and the fragments of artillery which covered the grounds, that a peloton of dragoons came thundering past, while a voice shouted out “Place! place!” Supposing it was the Emperor himself, I drew up to one side, and uncovering my head, sat in patience till he had passed, when, with the speed of four horses urged to their utmost, a calèche flew by, two men dressed like couriers seated on the box. They made for the highroad towards Vienna, and soon disappeared in the distance.

“What can it mean?” said I, to an officer beside me; “not his Majesty, surely?”

“No, no,” replied he, smiling: “it is General Lebrun on his way to Paris with the news of the victory. The Emperor is down at Reygern yonder, where he has just written the bulletin. I warrant you he follows that calèche with his eye; he’d rather see a battery of guns carried off by the enemy than an axle break there this moment.”

Thus closed the great day of Austerlitz—a hundred cannons, forty-three thousand prisoners, and thirty-two colors being the spoils of this the greatest of even Napoleon’s victories.

We passed the night on the field of battle,—a night dark and starless. The heavens were, indeed, clothed with black, and a heavy atmosphere, lowering and gloomy, spread like a pall over the dead and the dying. Not a breath of air moved; and the groans of the wounded sighed through the stillness with a melancholy cadence no words can convey. Far away in the distance the moving lights marked where fatigue parties went in search of their comrades. The Emperor himself did not leave the saddle till nigh morning; he went, followed by an ambulance, hither and thither over the plain, recalling the names of the several regiments, enumerating their deeds of prowess, and even asking for many of the soldiers by name. He ordered large fires to be lighted throughout the field, and where medical assistance could not be procured, the officers of the staff might be seen covering the wounded with greatcoats and cloaks, and rendering them such aid as lay in their power.

Dreadful as the picture was,—fearful reverse to the gorgeous splendor of the vast army the morning sun had shone upon, and in the pride of strength and spirit,—yet even here was there much to make one feel that war is not bereft of its humanizing influences. How many a soldier did I see that night, blackened with powder, his clothes torn and ragged with shot, sitting beside a wounded comrade—now wetting his lips with a cool draught, now cheering his heart with words of comfort! Many, though wounded, were tending others less able to assist themselves. Acts of kindness and self-devotion—not less in number than those of heroism and courage—were met with at every step; while among the sufferers there lived a spirit of enthusiasm that seemed to lighten the worst pang of their agony. Many would cry out, as I passed, to know the fate of the day, and what became of this regiment or of that battalion. Others could but articulate a faint “Vive l’Empereur!” which in the intervals of pain they kept repeating, as though it were a charm against suffering; while one question met me every instant,—“What says the Petit Caporal? Is he content with us?” None were insensible to the glorious issue of that day; nor amid all the agony of death, dealt out in every shape of horror and misery, did I hear one word of anger or rebuke to him for whose ambition they had shed their heart’s blood.

Having secured a fresh horse, I rode forward in the direction of Austerlitz, where our cavalry, met by the chevaliers of the Russian Imperial Guard, sustained the greatest check and the most considerable loss of the day. The old dragoon who accompanied me warned me I should find few, if any, of our comrades living there.

“Ventrebleu! lieutenant, you can’t expect it. The first four squadrons went down like one man; for when our fellows fell wounded from their horses, they always sabred or shot them as they lay.”

I found this information but too correct. Lines of dead men lay beside their horses, ranged as they stood in battle, while before them lay the bodies of the Russian Guard, their gorgeous uniform all slashed with gold, marking them out amid the dull russet costumes of their comrades. In many places were they intermingled, and showed where a hand-to-hand combat had been fought; and I saw two clasped rigidly in each other’s grasp, who had evidently been shot by others while struggling for the mastery.

“I told you, mon lieutenant, it was useless to come here; this was à la mort while it lasted; and if it had continued much longer in the same fashion, it’s hard to say which of us had been going over the field now with lanterns.”

Too true, indeed! Not one wounded man did we meet with, nor did one human voice break the silence around us. “Perhaps,” said I, “they may have already carried up the wounded to the village yonder; I see a great blaze of light there. Bide forward, and learn if it be so.”

When I had dismissed the orderly, I dismounted from my horse, and walked carefully along the ridge of ground, anxious to ascertain if any poor fellow still remained alive amid that dreadful heap of dead. A low brushwood covered the ground in certain places; and here I perceived but few of the cavalry had penetrated, while the infantry were all tirailleurs of the Russian Guard, bayoneted by our advancing columns. As I approached the lake the ground became more rugged and uneven; and I was about to turn back, when my eye caught the faint glimmering of a light reflected in the water. Picketing my horse where he stood, I advanced alone towards the light, which I saw now was at the foot of a little rocky crag beside the lake. As I drew near, I stopped to listen, and could distinctly hear the deep tones of a man’s voice, as if broken at intervals by pain, while in his accents I thought I could trace a tone of indignant passion rather than of bodily suffering.

“Leave me, leave me where I am,” cried he, peevishly. “I thought I might have had my last few moments tranquil, when I staggered thus far.”

“Come, come, Comrade!” said another, in a voice of comforting; “come, thou wert never faint-hearted before. Thou hast had thy share of bruises, and cared little about them too. Art dry?”

“Yes; give me another drink. Ah!” cried he, in an excited tone, “they can’t stand before the cuirassiers of the Guard. Sacrebleu! how proud the Petit Caporal will be of this day!” Then, dropping his voice, he muttered, “What care I who’s proud? I have my billet, and must be going.”

“Not so, mon enfant; thou’lt have the cross for thy day’s work. He knows thee well; I saw him smile to-day when thou madest the salute in passing.”

“Didst thou that?” said the wounded man, with eagerness; “did he smile? Ah, villain! how you can allure men to shed their heart’s blood by a smile! He knows me! That he ought, and, if he but knew how I lay here now, he ‘d send the best surgeon of his staff to look after me.”

“That he would, and that he will; courage, and cheer up.”

“No, no; I don’t care for it now. I’ll never go back to the regiment again; I could n’t do it!”

As he spoke the last words his voice became fainter and fainter, and at last was lost in a hiccup; partly, as it seemed, from emotion, and partly from bodily suffering.

“Qui vive?” cried his companion, as the clash of my sabre announced my approach.

“An officer of the Eighth Hussars,” said I, in a low voice, fearing to disturb the wounded man, as he lay with his head sunk on his knees.

“Too late, Comrade! too late,” said he, in a stifled tone; “the order of route has come. I must away.”

“A brave cuirassier of the Guard should never say so while he has a chance left to serve his Emperor in another field of battle.”

“Vive l’Empereur! vive l’Empereur!” shouted he, madly, as he lifted his helmet and tried to wave it above his head. But the exertion brought on a violent fit of coughing, which choked his utterance, while a torrent of red blood gushed from his mouth, and deluged his neck and chest.

“Ah, mon Dieu! that cry has been his death,” said the other, wringing his hands in utter misery.

“Where is he wounded?” said I, kneeling down beside the sick man, who now lay, half on his face, upon the grass.

“In the chest, through the lung,” whispered the other. “He doesn’t know the doctor saw him; it was he told me there was no hope. ‘You may leave him,’ said he; ‘an hour or two more are all that ‘s left him;’ as if I could leave a comrade we all loved. My poor fellow, it is a sad day for the old Fourth when thou art taken from them!”

“Ha! was he of the Fourth, then?” said I, remembering the regiment.

“Yes, parbleu! and though but a corporal, he was well known throughout the army. Pioche—”

“Pioche!” cried I, in agony; “is this Pioche?”

“Here,” said the wounded man, hearing the name, and answering as if on parade,—“here, mon commandant! but too faint, I ‘m afraid, for duty. I feel weak to-day,” said he, as he pressed his hand upon his side, and then slowly sank back against the rock, and dropped his arms at either side.

“Come,” said I, “we must lose no time. Let us carry him to the rear. If nothing else can be done, he ‘ll meet with care—”

“Hush! mon lieutenant! don’t let him hear you speak of that. He stormed and swore so much when the ambulance passed, and they wanted to bring him along, that it brought on a coughing fit, just like what you saw, and he lay in a faint for half an hour after. He vows he ‘ll never stir from where he is. Truth is, Commandant,” said he, in the lowest whisper, “he is determined to die. When his squadron fell back from the Russian square, he rode on their bayonets, and cut at the men while the artillery was playing all about him. He told me this morning he ‘d never leave the field.”

“Poor fellow! what was the meaning of this sad resolution?”

“Ma foi! a mere trifle, after all,” said the other, shrugging his shoulders, and making a true French grimace of contempt. “You ‘ll smile when I tell you; but he takes it to heart, poor fellow. His mistress has been false to him,—no great matter that, you ‘d say,—but so it is, and nothing more. See how still he lies now! is he sleeping?”

“I fear not; he looks exhausted from loss of blood. Come, we must have him out of this; here comes my orderly to assist us. If we carry him to the road I ‘ll find a carriage of some sort.”

I said this in a tone of command, to silence any scruples he might still have about obeying his comrade in preference to the orders of an officer. He obeyed with the instinct of discipline, and proceeded to fold his cloak in such a manner that we could carry the wounded man between us.

The poor corporal, too weak to resist us, faint from bleeding and semi-stupid, suffered himself to be lifted upon the cloak, and never uttered a word or a cry as we bore him along between us.

We had not proceeded far when we came up with a convoy, conducting several carts with the wounded to the convent of Reygern, which had now been fitted up as an hospital. On one of these we secured a place for our poor friend, and walked along beside him towards the convent. As we went along I questioned his comrade closely on the point; and he told me that Pioche had resolved never to survive the battle, and had taken leave of his friends the evening before.

“Ah, parbleu!” added he, with energy, “mademoiselle is pretty enough,—there ‘s no denying that; but her head is turned by flattery and soft speeches. All the gay young fellows of the hussar regiment, the aides-de-camp,—ay, and some of the generals, too,—have paid her so much attention that it could not be expected she’d care for a poor corporal. Not but that Pioche is a brave fellow and a fine soldier. Sapristi! he ‘d be no discredit to any girl’s choice. But Minette—”

“Minette, the vivandière?”

“Ay, to be sure, mon lieutenant; I’d warrant you must have known her.”

“What of her? where is she?” said I, burning with impatience.

“She’s with the wounded, up at Reygern yonder. They sent for her to Heilbrunn yesterday, where she was with the reserve battalions. Ma foi! you don’t think our fellows would do without Minette at the ambulance, where there was a battle to be fought. They say they’d hard work enough to make her come up. After all, she’s a strange girl; that she is.”

“How was that? Has she taken offence with the Fourth?”

“No, that is not it; she likes the old regiment in her heart. I’d never believe she didn’t; but” (here he dropped his voice to a low whisper, as if dreading to be overheard by the wounded man), “but they say—who knows if it’s true?—that when she was left behind at Ulm or Elchingen, or somewhere up there on the Danube, that there was a young fellow—I heard his name, too, but I forget it—who was brought in badly wounded, and that mademoiselle was left to watch and nurse him. He got well in time, for the thing was not so serious as they thought. And what do you think was the return he made the poor girl? He seduced her!”

“It’s false! false as hell!” cried I, bursting with passion. “Who has dared to spread such a calumny?”

“Don’t be angry, mon lieutenant; there are plenty to answer for the report. And if it was yourself—”

“Yes; it was by my bedside she watched; it was to me she gave that care and kindness by which I recovered from a dangerous wound. But so far from this base requital—”

“Why did she leave you, then, and march night and day with the chasseur brigade into the Tyrol? Why did she tell her friends that she’d never see the old Fourth again? Why did she fret herself into an illness—”

“Did she do this, poor girl?”

“Ay, that she did. But, mayhap, you never heard of all this. I can only say, mon lieutenant, that you’d be safer in a broken square, charged by a heavy squadron, than among the Fourth, after what you ‘ve done.”

I turned indignantly from him without a reply; for while my pride revolted at answering an accusation from such a quarter, my mind was harassed by the sad fate of poor Minette, and perplexed how to account for her sudden departure. My silence at once arrested my companion’s speech, and we walked along the remainder of the way without a word on either side.

The day was just breaking when the first wagon of the convoy entered the gates of the convent. It was an enormous mass of building, originally destined for the reception of about three thousand persons; for, in addition to the priestly inhabitants, there were two great hospitals and several schools included within the walls. This, before the battle, had been tenanted by the staffs of many general officers and the corps of engineers and sappers, but now was entirely devoted to the wounded of either army; for Austrians and Russians were everywhere to be met with, receiving equal care and attention with our own troops.

It was the first time I had witnessed a military hospital after a battle, and the impression was too fearful to be ever forgotten by me.

The great chambers and spacious rooms of the convent were soon found inadequate for the numbers who arrived; and already the long corridors and passages of the building were crowded with beds, between which a narrow path scarcely permitted one person to pass. Here, promiscuously, without regard to rank, officers in command lay side by side with the meanest privates, awaiting the turn of medical aid, as no other order was observed than the necessities of each case demanded. A black mark above the bed, indicating that the patient’s state was hopeless, proclaimed that no further attention need be bestowed; while the same mark, with a white bar across it, implied that it was a case for operation. In this way the surgeons who arrived at each moment from different corps of the army discovered, at a glance, where their services were required, and not a minute’s time was lost.

The dreadful operations of surgery—for which, in the events of every-day life, every provision of delicate secrecy, and every minute detail which can alleviate dread, are so rigidly studied,—were here going forward on every side; the horrible preparations moved from bed to bed with a rapidity which showed that where suffering so abounded there was no time for sympathy; and the surgeons, with arms bare to the shoulder and bedaubed with blood, toiled away as though life no longer moved in the creeping flesh beneath the knife, and human agony spoke not aloud with every motion of their hand.

“Place there! move forward!” said an hospital surgeon, as they carried up the litter on which Pioche lay stretched and senseless.

“What’s this?” cried a surgeon, leaning forward, and placing his hand on the sick man’s pulse. “Ah! take him back again; it ‘s all over there!”

“Oh, no!” cried I, in agony, “it can scarcely be; they lifted him alive from the wagon.”

“He’s not dead, sir,” replied the surgeon, in a whisper, “but he will soon be; there’s internal bleeding going on from that wound, and a few hours, or less perhaps must close the scene.”

“Can nothing be done? nothing?”

“I fear not.” He opened the jacket of the wounded man as he spoke, and slitting the inner clothes asunder with a quick stroke of his scissors, disclosed a tremendous sabre-wound in the side. “That is not the worst,” said he. “Look here,” pointing to a small bluish mark of a bullet hole above it; “here lies the mischief.”

An hospital aid whispered something at the instant in the surgeon’s ear, to which he quickly replied, “When?”

“This instant, sir; the ligature slipped, and—”