The Project Gutenberg EBook of Tom Burke Of "Ours", Volume I (of II), by Charles James Lever This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Tom Burke Of "Ours", Volume I (of II) Author: Charles James Lever Illustrator: Phiz. Release Date: April 6, 2010 [EBook #31901] Last Updated: September 2, 2016 Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TOM BURKE OF "OURS", VOLUME *** Produced by David Widger

IN TWO VOLUMES VOL. I

Transcriber’s Note: Two print editions have been used for this Project Gutenberg Edition of “Tom Burke of ‘Ours’”: The Little Brown edition (Boston) of 1913 with illustrations by Phiz; and the Chapman and Hall editon (London) of 1853 with illustrations by Browne. Illegible and missing pages were found in both print editions.

DW

| VOLUME TWO |

CONTENTS

PREFACE.

TOM BURKE OF “OURS."

CHAPTER I. MYSELF

CHAPTER II. DARBY THE “BLAST.”

CHAPTER III. THE DEPARTURE

CHAPTER IV. MY WANDERINGS

CHAPTER V. THE CABIN

CHAPTER VI. MY EDUCATION

CHAPTER VII. KEVIN STREET

CHAPTER VIII. NO. 39, AND ITS FREQUENTERS

CHAPTER IX. THE FRENCHMAN’S STORY

CHAPTER X. THE CHURCHYARD

CHAPTER XI. TOO LATE

CHAPTER XII. A CHARACTER

CHAPTER XIII. AN UNLOOKED-FOR VISITOR

CHAPTER XIV. THE JAIL

CHAPTER XV. THE CASTLE

CHAPTER XVI. THE BAIL

CHAPTER XVII. MR. BASSET’S DWELLING

CHAPTER XVIII. THE CAPTAIN’S QUARTERS

CHAPTER XIX. THE QUARREL

CHAPTER XX. THE FLIGHT

CHAPTER XXI. THE ÉCOLE MILITAIRE

CHAPTER XXII. THE TUILERIES IN 1803

CHAPTER XXIII. A SURPRISE

CHAPTER XXIV. THE PAVILLON DE FLORE

CHAPTER XXV. THE SUPPER AT “BEAUVILLIERS’S”

CHAPTER XXVI. THE TWO VISITS

CHAPTER XXVII. THE MARCH TO VERSAILLES

CHAPTER XXVIII. THE PARK OF VERSAILLES

CHAPTER XXIX. LA ROSE OF PROVENCE

CHAPTER XXX. A WARNING

CHAPTER XXXI. THE CHÂTEAU

CHAPTER XXXII. THE CHÂTEAU d’ANCRE

CHAPTER XXXIII. THE TEMPLE

CHAPTER XXXIV. THE CHOUANS

CHAPTER XXXV. THE REIGN OF TERROR UNDER THE CONSULATE

CHAPTER XXXVI. THE PALAIS DE JUSTICE

CHAPTER XXXVII. THE TRIAL

CHAPTER XXXVIII. THE CUIRASSIER

CHAPTER XXXIX. A MORNING AT THE TUILLERIES

CHAPTER XL. A NIGHT IN THE TUILERIES GARDENS

CHAPTER XLI. A STORY OF THE YEAR ‘92

CHAPTER XLII. THE HALL OF THE MARSHALS

CHAPTER XLIII. THE MARCH ON THE DANUBE

CHAPTER XLIV. THE CANTEEN

CHAPTER XLV. THE “VIVANDIÈRE OF THE FOURTH”

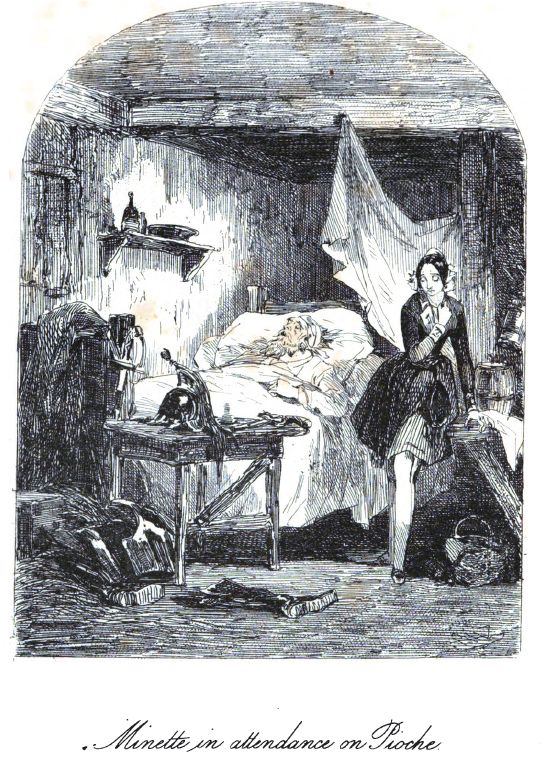

ILLUSTRATIONS

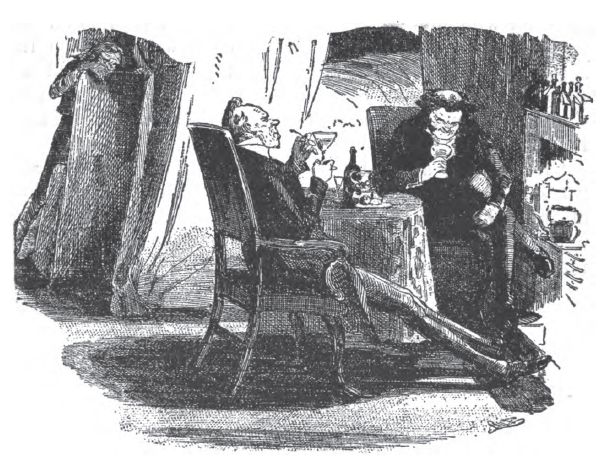

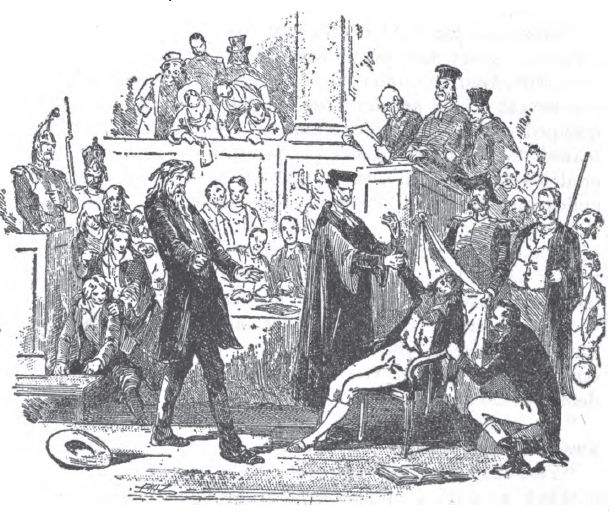

Law and Physic in the Chamber of Death

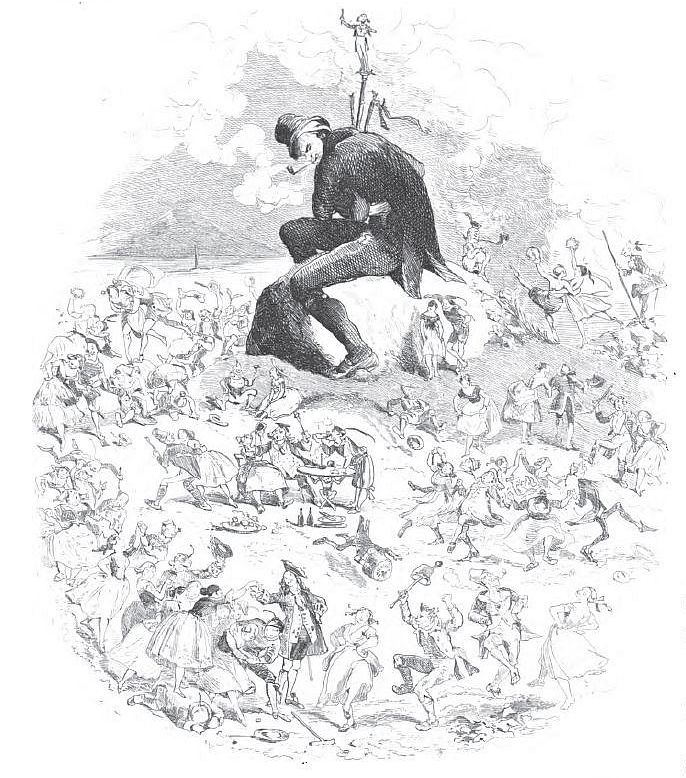

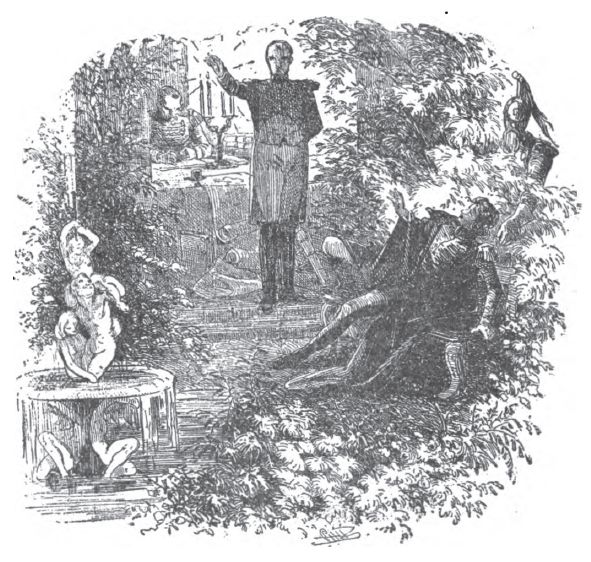

Saldin Danceth a Lively Measure

Tom Receives a Strange Visitor

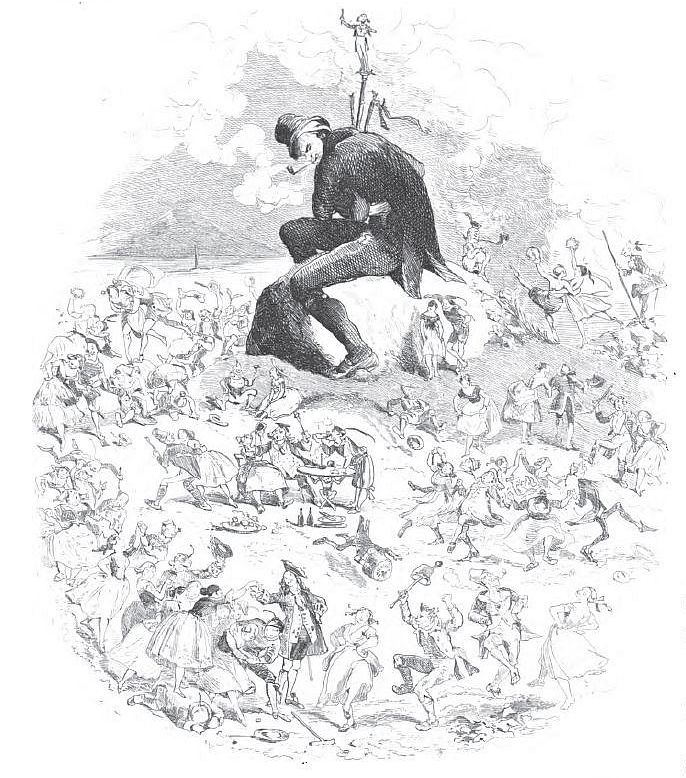

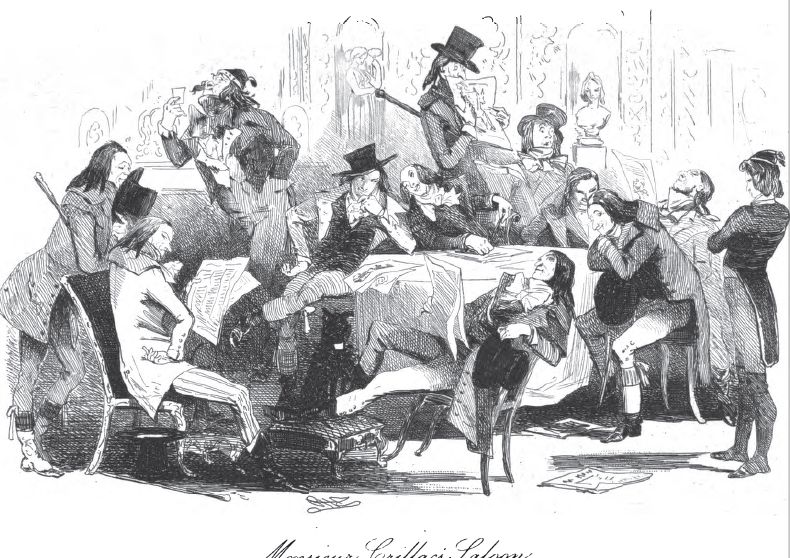

May Good Digestion Wait on Appetite

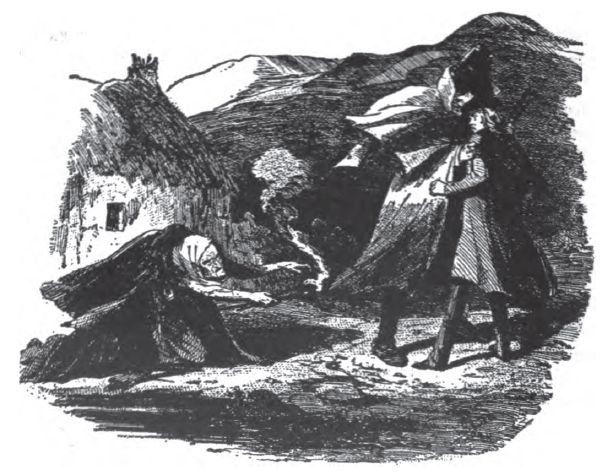

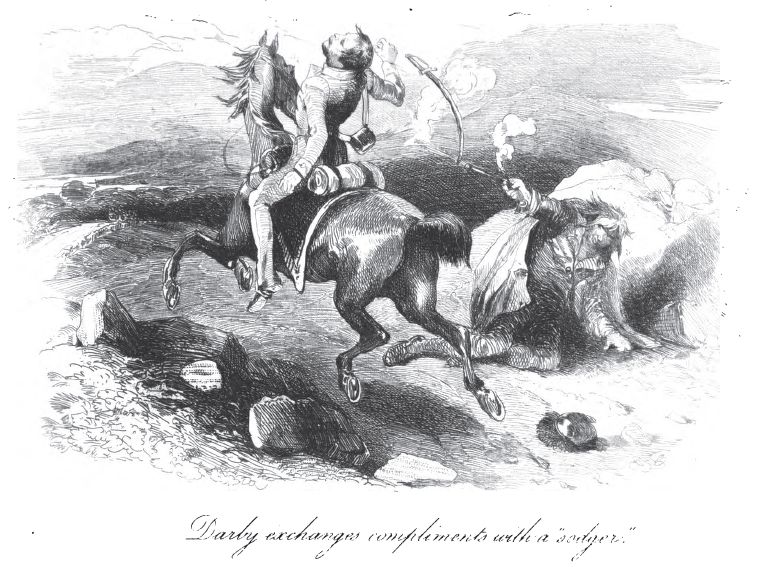

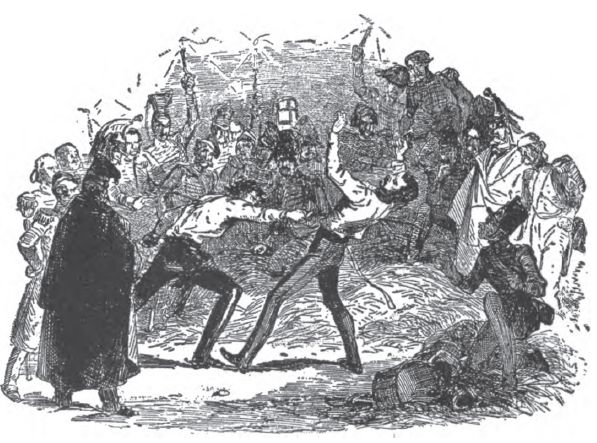

Darby Exchanges Compliments With a “sodger”

Napoleon Sends Burke from the Room

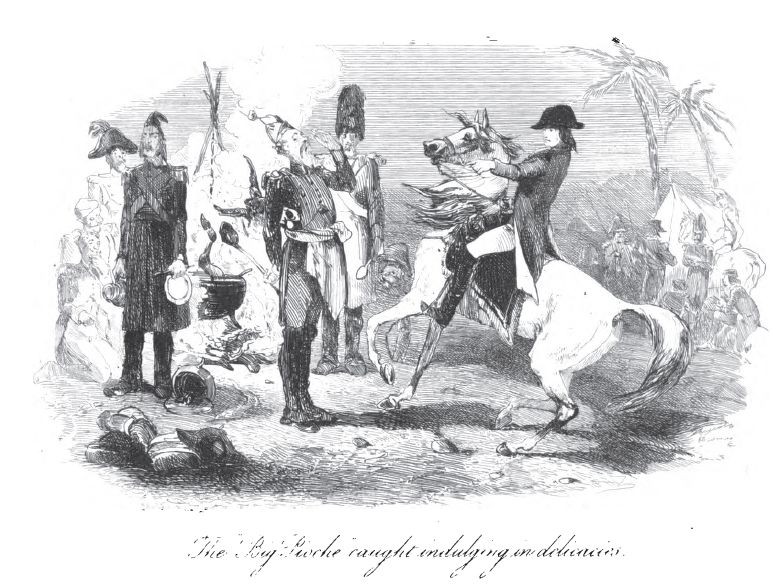

The “big Pioche” Indulging in Delicacies

TO MISS EDGEWORTH.

Madam,—This weak attempt to depict the military life of France, during the brief but glorious period of the Empire, I beg to dedicate to you. Had the scene of this, like that of my former books, been laid chiefly in Ireland, I should have felt too sensibly my own inferiority to venture on the presumption of such a step. As it is, I never was more conscious of the demerits of my volume than when inscribing it to you; but I cannot resist the temptation of being, even thus, associated with a name,—the first in my country’s literature.

Another motive I will not conceal,—the ardent desire I have to assure you, that, amid the thousands you have made better, and wiser, and happier, by your writings, you cannot count one who feels more proudly the common tie of country with you, nor more sincerely admires your goodness and your genius, than

Your devoted and obedient servant,

CHARLES J. LEVER.

Temple-O, Nov. 25, 1848.

PREFATORY EPISTLE FROM MR. BURKE.

My dear O’Flaherty,—It seems that I am to be the “next devoured.” Well, be it so; my story, such as it is, you shall have. Only one condition would I bargain for,—that you seriously disabuse your readers of the notion that the life before them was one either of much pleasure or profit. I might moralize a little here about neglected opportunities and mistaken opinions; but, as I am about to present you with my narrative, the moral—if there be one—need not be anticipated.

I believe I have nothing else to premise, save that if my tale have little wit, it has some warning; and as Bob Lambert observed to the hangman who soaped the rope for his execution, “even that same ‘s a comfort.” If our friend Lorrequer, then, will as kindly facilitate my debut, I give him free liberty to “cut me down” when he likes, and am,

Yours, as ever,

TOM BURKE.

To T. O’Flaherty, Esq.

I WAS led to write this story by two impulses: first, the fascination which the name and exploits of the great Emperor had ever exercised on my mind as a boy; and secondly, by the favorable notice which the Press had bestowed upon my scenes of soldier life in “Charles O’Malley.”

If I had not in the wars of the Empire the patriotic spirit of a great national struggle to sustain me, I had a field far wider and grander than any afforded by our Peninsular campaigns; while in the character of the French army, composed as it was of elements derived from every rank and condition, there were picturesque effects one might have sought for in vain throughout the rest of Europe.

It was my fortune to have known personally some of those who filled great parts in this glorious drama. I had listened over and over to their descriptions of scenes, to which their look, and voice, and manner imparted a thrilling intensity of interest. I had opportunities of questioning them for explanations, of asking for solutions of this and that difficulty which had puzzled me, till I grew so familiar with the great names of the time, the events, and even the localities, that when I addressed myself to my tale, it was with a mind filled by my topics to the utter exclusion of all other subjects.

Neither before nor since have I ever enjoyed to the same extent the sense of being so entirely engrossed by a single theme. A great tableau of the Empire, from its gorgeous celebrations in Paris to its numerous achievements on the field of battle, was ever outspread before me, and I sat down rather to record than to invent the scenes of my story. A feeling that, as I treated of real events I was bound to maintain a degree of accuracy in relation to them, even in fiction, made me endeavor to possess myself of a correct knowledge of localities, and, so far as I was able, with a due estimate of those whose characters I discussed.

Some of the battlefields I have gone over; of others, I have learned the particulars from witnesses of the great struggles that have made them famous. To the claim of this exactness I have, therefore, the pretension of at least the desire to be faithful. For my story, it has all the faults and shortcomings which beset everything I have ever written; for these I can but offer regrets, only the more poignant that I feel how justly they are due.

The same accuracy which I claim for scenes and situations, I should like, if I dared, to claim for the individuals who figure in this tale; but I cannot, in any fairness, pretend to more than an attempt to paint resemblances of those whom I have myself admired in the description of others. Pioche and Minette are of this number. So is, but of a very different school, the character of Duchesne; for which, however, I had what almost amounted to an original. As to the episodes of this story, one or two were communicated as facts; the others are mere invention.

I do not remember any particulars to which I should further advert; while I feel, that the longer I dwell upon the theme, the more occasion is there to entreat indulgence,—an indulgence which, if you are not weary of according, will be most gratefully accepted by

Your faithful servant,

CHARLES LEVER

Casa Capponi, Florence, May, 1867.

It was at the close of a cold, raw day in January—no matter for the year—that the Gal way mail was seen to wind its slow course through that long and dull plain that skirts the Shannon, as you approach the “sweet town of Athlone.” The reeking box-coats and dripping umbrellas that hung down on every side bespoke a day of heavy rain, while the splashed and mud-stained panels of the coach bore token of cut-up roads, which the jaded and toil-worn horses amply confirmed. If the outsiders—with hats pressed firmly down, and heads bent against the cutting wind—presented an aspect far from comfortable, those within, who peeped with difficulty through the dim glass, had little to charm the eye; their flannel nightcaps and red comforters were only to be seen at rare intervals, as they gazed on the dreary prospect, and then sank back into the coach to con over their moody thoughts, or, if fortunate, perhaps to doze.

In the rumble, with the guard, sat one whose burly figure and rosy cheeks seemed to feel no touch of the inclement wind that made his companions crouch. An oiled-silk foraging-cap fastened beneath the chin, and a large mantle of blue cloth, bespoke him a soldier, if even the assured tone of his voice and a certain easy carriage of his head had not conveyed to the acute observer the same information. Unsubdued in spirit, undepressed in mind, either by the long day of pouring rain or the melancholy outline of country on every side, his dark eye flashed as brightly from beneath the brim of his cap, and his ruddy face beamed as cheerily, as though Nature had put forth her every charm of weather and scenery to greet and delight him. Now inquiring of the guard of the various persons whose property lay on either side, the name of some poor hamlet or some humble village; now humming to himself some stray verse of an old campaigning song,—he passed his time, diversifying these amusements by a courteous salute to a gaping country girl, as, with unmeaning look, she stared at the passing coach. But his principal occupation seemed to consist in retaining one wing of his wide cloak around the figure of a little boy, who lay asleep beside him, and whose head jogged heavily against his arm with every motion of the coach.

“And so that’s Athlone, yonder, you tell me,” said the captain, for such he was,—“‘the sweet town of Athlone, ochone!’ Well, it might be worse. I ‘ve passed ten years in Africa,—on the burning coast, as they call it: you never light a fire to cook your victuals, but only lay them before the sun for ten minutes, game something less, and the joint’s done; all true, by Jove! Lie still, my young friend, or you’ll heave us both over! And whereabouts does he live, guard?”

“Something like a mile and a half from here,” replied the gruff guard.

“Poor little fellow! he’s sleeping it out well. They certainly don’t take overmuch care of him, or they’d never have sent him on the top of a coach in weather like this, without even a greatcoat to cover him. I say, Tom, my lad, wake up; you’re not far from home now. Are you dreaming of the plum-pudding and the pony and the big spaniel, eh?”

“Whisht!” said the guard, in a low whisper. “The chap’s father is dying, and they’ve sent for him from school to see him.”

A loud blast of the horn now awoke me thoroughly from the half-dreamy slumber in which I had listened to the previous dialogue, and I sat up and looked about me. Yes, reader, my unworthy self it was who was then indulging in as pleasant a dream of home and holidays as ever blessed even a schoolboy’s vigils. Though my eyes were open, it was some minutes before I could rally myself to understand where I was, and with what object. My senses were blunted by cold, and my drenched limbs were cramped and stiffened; for the worthy captain, to whose humanity I owed the share of his cloak, had only joined the coach late in the day, and during the whole morning I had been exposed to the most pitiless downpour of rain and sleet.

“Here you are!” said the rough guard, as the coach drew up to let me down. “No need of blowing the horn here, I suppose?”

This was said in allusion to the miserable appearance of the ruined cabin that figured as my father’s gate lodge, where some naked children were seen standing before the door, looking with astonishment at the coach and passengers.

“Well, good-by, my little man. I hope you ‘ll find the governor better. Give him my respects; and, hark ye, if ever you come over to Athlone, don’t forget to come and see me: Captain Bubbleton,—George Frederick Augustus Bubbleton, Forty-fifth Regiment; or, when at home, Little Bubbleton, Herts, and Bungalow Hut, in the Carnatic^ that’s the mark. So good-by! good-by!”

I waved my hand to him in adieu, and then turned to enter the gate.

“Well, Freney,” said I, to a half-dressed, wild-looking figure that rushed out to lift the gate open,—for the hinges had been long broken, and it was attached to the pier by some yards of strong rope,—“how is my father?”

A gloomy nod and a discouraging sign with his open hand were the only reply.

“Is there any hope?” said I, faintly.

“Sorrow one of me knows; I dare n’t go near the house. I was sarved with notice to quit a month ago, and they tell him I ‘m gone. Oh vo, vo! what ‘s to become of us all!”

I threw the bag which contained my humble wardrobe on my shoulder, and without waiting for further questioning, walked forward. Night was falling fast, and nothing short of my intimacy with the place from infancy could have enabled me to find my way. The avenue, from long neglect and disuse, was completely obliterated; the fences were broken up to burn; the young trees had mostly shared the same fate; the cattle strayed at will through the plantations; and all bespoke utter ruin and destruction.

If the scene around me was sad, it only the better suited my own heart. I was returning to a home where I had never heard the voice of kindness or affection; where one fond word, one look of welcome, had never met me. I was returning, not to receive the last blessing of a loving parent, but merely sent for as a necessary ceremony on the occasion. And perhaps there was a mock propriety in inviting me once more to the house which I was never to revisit. My father, a widower for many years, had bestowed all his affection on my elder brother, to whom so much of his property as had escaped the general wreck was to descend. He had been sent to Eton under the guidance of a private tutor, while an obscure Dublin school was deemed good enough for me. For him every nerve was strained to supply all his boyish extravagance, and enable him to compete with the sons of men of high rank and fortune, whose names, mentioned in his letters home, were an ample recompense for all the lavish expenditure their intimacy entailed. My letters were few and brief; their unvaried theme the delay in the last quarter’s payment, or the unfurnished condition of my little trunk, which more than once exposed me to the taunts of my schoolfellows.

He was a fair and delicate boy, timid in manner and retiring in disposition; I, a browned-faced varlet, who knew every one from the herd to the high-sheriff. To him the servants were directed to look up as the head of the house; while I was consigned either to total neglect, or the attentions of those who only figured as supernumeraries in our Army List. Yet, with all these sources of jealousy between us, we loved each other tenderly. George pitied “poor Tommy,” as he called me; and for that very pity my heart clung to him. He would often undertake to plead my cause for those bolder infractions his gentle nature never ventured on; and it was only from long association with boys of superior rank, whose habits and opinions he believed to be standards for his imitation, that » at length a feeling of estrangement grew up between us, and we learned to look somewhat coldly on each other.

From these brief details it will not be wondered at it I turned homeward with a heavy heart. From the hour I received the letter of my recall—which was written by my father’s attorney in most concise and legal phrase—I had scarcely ceased to shed tears; for so it is, there is something in the very thought of being left an orphan, friendless and unprotected, quite distinct from the loss of affection and kindness which overwhelms the young heart with a very flood of wretchedness. Besides, a stray word or two of kindness had now and then escaped my father towards me, and I treasured these up as my richest possession. I thought of them over and over. Many a lonely night, when my heart has been low and sinkings I repeated them to myself, like talismans against grief; and when I slept, my dreams would dwell on them and make my waking happy.

As I issued from a dark copse of beech-trees, the indistinct outline of the old house met my eye. I could trace the high-pitched roof, the tall and pointed gables against the sky; and with a strange sense of undefinable fear,’ beheld a solitary light that twinkled from the window of an upper room, where my father lay. The remainder of the building was in deep shadow. I mounted the long flight of stone steps that led to what once had been a terrace; but the balustrades were broken many a year ago; and even the heavy granite stone had been smashed in several places. The hall door lay wide open, and the hall itself had no other light save such as the flickering of a wood fire afforded, as its uncertain flashes fell upon the dark wainscot and the floor.

I had just recognized the grim, old-fashioned portraits that covered the walls, when my eye was attracted by a figure near the fire. I approached, and beheld an old man doubled with age. His bleared eyes were bent upon the wood embers, which he was trying to rake together with a stick; his clothes bespoke the most miserable poverty, and afforded no protection against the cold and cutting blast. He was croning some old song to himself as I drew near, and paid no attention to me. I moved round so as to let the light fall on his face, and then perceived it was old Lanty, as he was called. Poor fellow! Age and neglect had changed him sadly since I had seen him last. He had been the huntsman of the family for two generations; but having somehow displeased my father one day at the cover, he rode at him and struck him on the head with his loaded whip. The man fell senseless from his horse, and was carried home. A few days, however, enabled him to rally and be about again; but his senses had left him forever. All recollection of the unlucky circumstance had faded from his mind, and his rambling thoughts dwelt on his old pursuits; so that he passed his days about the stables, looking after the horses and giving directions about them. Latterly he had become too infirm for this, and never left his own cabin; but now, from some strange cause, he had come up to “the house,” and was sitting by the fire as I found him.

They who know Ireland will acknowledge the strange impulse which, at the approach of death, seems to excite the people to congregate about the house of mourning. The passion for deep and powerful excitement—the most remarkable feature in their complex nature—seems to revel in the details of sorrow and suffering. Not content even with the tragedy before them, they call in the aid of superstition to heighten the awfulness of the scene; and every story of ghost and banshee’ is conned over in tones that need not the occasion to make them thrill upon the heart. At such a time the deepest workings of their wild spirits are revealed. Their grief is low and sorrow-struck, or it is loud and passionate; now breaking into some plaintive wail over the virtues of the departed, now bursting into a frenzied appeal to the Father of Mercies as to the justice of recalling those from earth who were its blessing: while, stranger than all, a dash of reckless merriment will break in upon the gloom; but it is like the red lightning through the storm, that as it rends the cloud only displays the havoc and desolation around, and at its parting leaves even a blacker darkness behind it.

From my infancy I had been familiar with scenes of this kind; and my habit of stealing away unobserved from home to witness a country wake had endeared me much to the country-people, who felt this no small kindness from “the master’s son.” Somehow the ready welcome and attention I always met with had worked on my young heart, and I learned to feel all the interest of these scenes fully as much as those about me. It was, then, with a sense of desolation that I looked upon the one solitary mourner who now sat at the hearth,—that poor old idiot man who gazed on vacancy, or muttered with parched lip some few words to himself. That he alone should be found to join his sorrows to ours, seemed to me like utter destitution, and as I leaned against the chimney I burst into tears.

“Don’t cry, alannah! don’t cry,” said the old man; “it ‘s the worst way at all. Get up again and ride him at it bould. Oh vo! look at where the thief is taking now,—along the stonewall there!” Here he broke out into a low, wailing ditty:—

“And the fox set him down and looked about— And many were feared to follow; ‘Maybe I ‘m wrong,'says he, ‘but I doubt That you ‘ll be as gay to-morrow. For loud as you cry, and high as you ride, And little you feel my sorrow, I’ll be free on the mountain-side, While you ‘ll lie low to-morrow. Oh, Moddideroo, aroo, aroo!’”

“Ay, just so; they ‘ll run to earth in the cold churchyard. Whisht!—hark there! Soho, soho! That’s Badger I hear.”

I turned away with a bursting heart, and felt my way up the broad oak stair, which was left in complete darkness. As I reached the corridor, off which the bedrooms lay, I heard voices talking together in a low tone; they came from my father’s room, the door of which lay ajar. I approached noiselessly and peeped in: by the fire, which was the only light now in the apartment, sat two persons at a set table, one of whom I at once recognized as the tall, solemn-looking figure of Doctor Finnerty; the other I detected, by the sharp tones of his voice, to be Mr. Anthony Basset, my father’s confidential attorney.

On the table before them lay a mass of papers, parchments, leases, deeds, together with glasses and a black bottle, whose accompaniments of hot water and sugar left no doubt as to its contents. The chimney-piece was crowded with a range of vials and medicine bottles, some of them empty, some of them half finished.

From the bed in the corner of the room came the heavy sound of snoring respiration, which either betokened deep sleep or insensibility. If I enjoyed but little favor in my father’s house, I owed much of the coldness shown to me to the evil influence of the very two persons who sat before me in conclave. Of the precise source of the doctor’s dislike I was not quite clear, except, perhaps, that I recovered from the measles when he predicted my certain death; the attorney’s was, however, no mystery.

About three years before, he had stopped to breakfast at our house on his way to Ballinasloe fair. As his pony was led round to the stable, it caught my eye. It was a most tempting bit of horseflesh, full of spirit and in top condition, for he was going to sell it. I followed him round, and appeared just as the servant was about to unsaddle him. The attorney was no favorite in the house, and I had little difficulty in persuading the man, instead of taking off the saddle, merely to shorten the stirrups to the utmost limit. The next minute I was on his back flying over the lawn at a stretching gallop. Fences abounded on all sides, and I rushed him at double ditches, stone walls, and bog-wood rails, with a mad delight that at every leap rose higher. After about three quarters of an hour thus passed, his blood, as well as my own, being by this time thoroughly roused, I determined to try him at the wall of an old pound which stood some few hundred yards from the front of the house. Its exposure to the window at any other time would have deterred me from even the thought of such an exploit, but now I was quite beyond the pale of such cold calculations; besides that, I was accompanied by a select party of all the laborers, with their wives and children, whose praises of my horsemanship would have made me take the lock of a canal if before me. A tine gallop of grass sward led to the pound, and over this I went, cheered with as merry a cry as ever stirred a light heart. One glance I threw at the house as I drew near the leap. The window of the breakfast parlor was open; my father and Mr. Basset were both at it, I saw their faces red with passion; I heard their loud shout; my very spirit sickened within me. I saw no more; I felt the pony rush at the wall,—the quick stroke of his feet,—the rise,—the plunge,—and then a crash,—and I was sent spinning over his head some half-dozen yards, ploughing up the ground on face and hands. I was carried home with a broken head; the pony’s knees were in the same condition. My father said that he ought to be shot for humanity’s sake; Tony suggested the same treatment for me, on similar grounds. The upshot, however, was, I secured an enemy for life; and worse still, one whose power to injure was equalled by his inclination.

Into the company of these two worthies I now found myself thus accidentally thrown, and would gladly have retreated at once, but that some indescribable impulse to be near my father’s sickbed was on me; and so I crept stealthily in and sat down in a large chair at the foot of the bed, where unnoticed I listened to the long-drawn heavings of his chest, and in silence wept over my own desolate condition.

For a long time the absorbing nature of my own grief prevented me hearing the muttered conversation near the lire; but at length, as the night wore on and my sorrow had found vent in tears, I began to listen to the dialogue beside me.

“He ‘ll have five hundred pounds under his grandfather’s will, in spite of us. But what ‘s that?” said the attorney.

“I ‘ll take him as an apprentice for it, I know,” said the doctor, with a grin that made me shudder.

“That’s settled already,” replied Mr. Basset. “He’s to be articled to me for five years; but I think it ‘s likely he ‘ll go to sea before the time expires. How heavily the old man is sleeping! Now, is that natural sleep?”

“No, that’s always a bad sign; that puffing with the lips is generally among the last symptoms. Well, he’ll be a loss anyhow, when he’s gone. There’s an eight-ounce mixture he never tasted yet,—infusion of gentian with soda. Put your lips to that.”

“Devil a one o’ me will ever sup the like!” said the attorney, finishing his tumbler of punch as he spoke. “Faugh! how can you drink them things that way?”

“Sure it’s the compound infusion, made with orangepeel and cardamom seeds. There is n’t one of them did n’t cost two and ninepence. He ‘ll be eight weeks in bed come Tuesday next.”

“Well, well! If he lived till the next assizes, it would be telling me four hundred pounds; not to speak of the costs of two ejectments I have in hand against Mullins and his father-in-law.”

“It’s a wonder,” said the doctor, after a pause, “that Tom didn’t come by the coach. It’s no matter now, at any rate; for since the eldest son’s away, there’s no one here to interfere with us.”

“It was a masterly stroke of yours, doctor, to tell the old man the weather was too severe to bring George over from Eton. As sure as he came he’d make up matters with Tom; and the end of it would be, I ‘d lose the agency, and you would n’t have those pleasant little bills for the tenantry,—eh. Fin?”

“Whisht! he’s waking now. Well, sir; well, Mr. Burke, how do you feel now? He ‘s off again!”

“The funeral ought to be on a Sunday,” said Basset, in a whisper; “there ‘ll be no getting the people to come any other day. He ‘s saying something, I think.”

“Fin,” said my father, in a faint, hoarse voice,—“Fin, give me a drink. It ‘s not warm!”

“Yes, sir; I had it on the fire.”

“Well, then, it ‘s myself that ‘s growing cold. How ‘s the pulse now. Fin? Is the Dublin doctor come yet?”

“No, sir; we ‘re expecting him every minute. But sure, you know, we ‘re doing everything.”

“Oh! I know it. Yes, to be sure, Fin; but they ‘ve many a new thing up in Dublin there, we don’t hear of. Whisht! what’s that?”

“It ‘s Tony, sir,—Tony Basset; he ‘s sitting up with me.”

“Come over here, Tony. Tony, I’m going fast; I feel it, and my heart is low. Could we withdraw the proceedings about Freney?”

“He ‘s the biggest blackguard—”

“Ah! no matter now; I ‘m going to a place where we ‘ll all need mercy. What was it that Canealy said he ‘d give for the land?”

“Two pound ten an acre; and Freney never paid thirty shillings out of it.”

“It’s mighty odd George didn’t come over.”

“Sure, I told you there was two feet of snow on the ground.”

“Lord be about us, what a severe season! But why isn’t Tom here?” I started at the words, and was about to rush forward, when he added,—“I don’t want him, though.”

“Of course you don’t,” said the attorney; “it’s little comfort he ever gave you. Are you in pain there?”

“Ay, great pain over my heart. Well, well! don’t be hard to him when I ‘m gone.”

“Don’t let him talk so much,” said Basset, in a whisper, to the doctor.

“You must compose yourself, Mr. Burke,” said the doctor. “Try and take a sleep; the night isn’t half through yet.”

The sick man obeyed without a word; and soon after, the heavy respiration betokened the same lethargic slumber once more.

The voices of the speakers gradually fell into a low, monotonous sound; the long-drawn breathings from the sickbed mingled with them; the fire only sent forth an occasional gleam, as some piece of falling turf seemed to revive its wasting life, and shot up a myriad of bright sparks; and the chirping of the cricket in the chimney-corner sounded to my mournful heart like the tick of the death-watch.

As I listened, my tears fell fast, and a gulping fulness in my throat made me feel like one in suffocation. But deep sorrow somehow tends to sleep. The weariness of the long day and dreary night, exhaustion, the dull hum of the subdued voices, and the faint light, all combined to make me drowsy, and I fell into a heavy slumber.

I am writing now of the far-off past,—of the long years ago of my youth,—since which my seared heart has had many a sore and scalding lesson; yet I cannot think of that night, fixed and graven as it lies in my memory, without a touch of boyish softness. I remember every waking thought that crossed my mind: my very dream is still before me. It was of my mother. I thought of her as she lay on a sofa in the old drawing-room; the window open, and the blinds drawn, the gentle breeze of a June morning flapping them lazily to and fro as I knelt beside her to repeat my little hymn, the first I ever learned; and how at each moment my eyes would turn and my thoughts stray to that open casement, through which the odor of flowers and the sweet song of birds were pouring, and my little heart was panting for liberty, while her gentle smile and faint words bade me remember where I was. And then I was straying away through the old garden, where the very sunlight fell scantily through the thick-woven branches, loaded with perfumed blossoms; the blackbirds hopped fearlessly from twig to twig, mingling their clear notes with the breezy murmur of the leaves and the deep hum of summer bees. How happy was I then! And why cannot such happiness be lasting? Why can we not shelter ourselves from the base contamination of worldly cares, and live on amid pleasures pure as these, with hearts as holy and desires as simple as in childhood?

Suddenly a change came over my dream, and the dark clouds began to gather from all quarters, and a low, creeping wind moaned heavily along. I thought I heard ray name called. I started and awoke. For a second or two the delusion was so strong that I could not remember where I was; but as the gray light of a breaking morning fell through the half-open shutters, I beheld the two figures near the fire. They were both sound asleep, the deep-drawn breathing and nodding heads attesting the heaviness of their slumber.

I felt cold and cramped, but still afraid to stir, although a longing to approach the bedside was still upon me. A faint sigh and some muttered words here came to my ear, and I listened. It was my father; but so indistinct the sounds, they seemed more like the ramblings of a dream. I crept noiselessly on tiptoe to the bed, and drawing the curtain gently over, gazed within. He was lying on his back, his hands and arms outside the clothes. His beard had grown so much and he had wasted so far that I could scarcely have known him. His eyes were wide open, but fixed on the top of the bed; his lips moved rapidly, and by his hands, as they were closely clasped, I thought it was in prayer. I leaned over him, and placed my hand in his. For some time he did not seem to notice it; but at last he pressed it softly, and rubbing the fingers to and fro, he said, in a low, faint voice,—“Is this your hand, my boy?”

I thought my heart had split, as in a gush of tears I bent down and kissed him.

“I can’t see well, my dear; there’s something between me and the light, and a weight is on me—here—here—”

A heavy sigh, and a shudder that shook his whole frame, followed these words.

“They told me I wasn’t to see you once again,” said he, as a sickly smile played over his mouth; “but I knew you’d come to sit by me. It ‘s a lonely thing not to have one’s own at such an hour as this. Don’t weep, my dear, my own heart’s failing me fast.”

A broken, muttering sound followed, and then he said, in a loud voice; “I never did it! it was Tony Basset. He told me,—he persuaded me. Ah! that was a sore day when I listened to him. Who ‘s to tell me I ‘m not to be master of my own estate? Turn them adrift,—ay, every man of them. I ‘ll weed the ground of such wretches,—eh, Tony? Did any one say Freney’s mother was dead? they may wake her at the cross roads, if they like. Poor old Molly! I ‘m sorry for her, too. She nursed me and my sister that’s gone; and maybe her deathbed, poor as she was, was easier than mine will be,—without kith or kin, child or friend. Oh, George!—and I that doted on you with all my heart! Whose hand’s this? Ah, I forgot; my darling boy, it’s you. Come to me here, my child! Was n’t it for you that I toiled and scraped this many a year? Wasn’t it for you that I did all this? and—God, forgive me!—maybe it ‘s my soul that I ‘ve perilled to leave you a rich man. Where ‘s Tom? where ‘s that fellow now?”

“Here, sir!” said I, squeezing his hand, and pressing it to my lips.

He sprang up at the words, and sat up in his bed, his eyes dilated to their widest, and his pale lips parted asunder.

“Where?” cried he, as he felt me over with his thin fingers, and drew me towards him.

“Here, father, here!”

“And is this Tom?” said he, as his voice fell into a low, hollow sound; and then added: “Where’s George? answer me at once. Oh, I see it! He isn’t here; he would n’t come over to see his old father. Tony! Tony Basset, I say!” shouted the sick man, in a voice that roused the sleepers, and brought them to his bedside, “open that window there. Let me look out,—do it as I bid you,—open it wide. Turn in all the cattle you can find on the road. Do you hear me, Tony? Drive them in from every side. Finnerty, I say, mind my words; for” (here he uttered a most awful and terrific oath), “as I linger on this side of the grave, I ‘ll not leave him a blade of grass I can take from him.”

His chest heaved with a convulsive spasm; his face became pale as death; his eyes fixed; he clutched eagerly at the bedclothes; and then, with a horrible cry, he fell back upon the pillow, as a faint stream of red blood trickled from his nostril and ran down his chin.

“It ‘s all over now!” whispered the doctor.

“Is he dead?” said Basset.

The other made no reply; but drawing the curtains close, he turned away, and they both moved noiselessly from the room.

If there are dreams which, by their vividness and accuracy of detail, seem altogether like reality, so are there certain actual passages in our lives which, in their indistinctness while occurring, and in the faint impression they leave behind them, seem only as mere dreams. Most of our early sorrows are of this kind. The warm current of our young hearts would appear to repel the cold touch of affliction; nor can grief at this period do more than breathe an icy chill upon the surface of our affections, where all is glowing and fervid beneath. The struggle then between the bounding heart and the depressing care renders our impressions of grief vague and ill defined.

A stunning sense of some great calamity, some sorrow without hope, mingled in my waking thoughts with a childish notion of freedom. Unloved, uncared for, my early years presented but few pleasures. My boyhood had been a long struggle to win some mark of affection from one who cared not for me, and to whom still my heart had clung, as does the drowning man to the last plank of all the wreck. The tie that bound me to him was now severed, and I was without-one in the wide world to look up to or to love.

I looked out from my window upon the bleak country. A heavy snowstorm had fallen during the night. A lowering sky of leaden hue stretched above the dreary landscape, across which no living thing was seen to move. Within doors all was silent. The doctor and the attorney had both taken their departure; the deep wheel-track in the snow marked the road they had followed. The servants, seated around the kitchen fire, conversed in low and broken whispers. The only sound that broke the stillness was the ticking of the clock upon the stair. There was something that smote heavily on my heart in the monotonous ticking of that clock: that told of time passing beside him who had gone; that seemed to speak of minutes close to one whose minutes were eternity. I crept into the room where the dead body lay, and as my tears ran fast, I bent over it. I thought sometimes the expression of those cold features changed,—now frowning heavily, now smiling blandly on me. I watched them, till in my eager gaze the lips seemed to move and the cheek to flush. How hard is it to believe in death! how difficult to think that “there is a sleep that knows no waking!” I knelt down beside the bed and prayed. I prayed that now, as all of earth was nought to him who was departed, he would give me the affection he had not bestowed in life. I besought him not to chill the heart that in its lonely desolation had neither home nor friend. My throat sobbed to bursting as in my words I seemed to realize the fulness of my affliction. The door opened behind me as with bent-down head I knelt. A heavy footstep slowly moved along the floor; and the next moment the tottering figure of old Lanty stood beside me, gazing on the dead man. There was that look of vacancy in his filmy eye that showed he knew nothing of what had happened.

“Is he asleep. Master Tommy?” said the old man, in a faint whisper.

My lips trembled, but I could not speak the word.

“I thought he wanted the ‘dogs’ up at Meelif; but I ‘m strained here about the loins, and can’t go out myself. Tell him that, when he wakes.”

“He’ll never wake now, Lanty; he’s dead!” said I, as a rush of tears half choked my utterance.

“Dead!” said he, repeating the word two or three times,—“dead! Well, well! I wonder will Master George keep the dogs now. There seldom comes a better; and ‘twas himself that liked the cry o’ them.”

He tottered from the room as he spoke, and I could hear him muttering the same words over and over, as he crept slowly down the stair.

I have said that this painful stroke of fortune was as a dream to me; and so for three days I felt it. The altered circumstances of everything about me were inexplicable to my puzzled brain. The very kindness of the servants, so unusual to me, struck me forcibly. They felt that the time was past when any sympathy for me had been the passport to disfavor, and they pitied me.

The funeral took place on the third morning. Mr. Basset having acquainted my brother that there was no necessity for his presence, even that consolation was denied me,—to meet him who alone remained of all my name and house belonging to me. How I remember every detail of that morning! The silence of the long night broken in upon by heavy footsteps ascending the stairs; strange voices, not subdued like those of all in our little household, but loud and coarse; even laughter I could hear, the noise increasing at each moment. Then the muffled sound of wheels upon the snow, and the cries of the drivers as they urged their horses forward. Then a long interval, in which nought was heard save the happy whistle of some poor postilion, who, careless of his errand, whiled away the tedious time with a lively tune. And lastly, there came the dull noise of feet moving step by step down the stair, the muttered words, the shuffling sound of feet as they descended, and the clank of the coffin as it struck against the wall.

The long, low parlor was filled with people, few of whom I had ever seen before. They were broken up into little knots, chatting cheerfully together while they made a hurried breakfast. The table and sideboard were covered with a profusion I had never witnessed previously. Decanters of wine passed freely from hand to hand; and although the voices fell somewhat as I appeared amidst them, I looked in vain for one touch of sorrow for the dead, or even respect for his memory.

As I took my place in the carriage beside the attorney, a kind of dreamy apathy settled down on me, and I scarcely knew what was passing. I only remember the horrible shrinking sense of dread with which I recoiled from his one attempt at consolation, and the abrupt way in which he desisted, and turned to converse with the doctor. How my heart sickened as we drew near the churchyard, and I beheld the open gate that stood wide awaiting us! The dusky figures, with their mournful black cloaks, moved slowly across the snow, like spirits of some gloomy world; while the death-bell echoed in my ears, and sent a shuddering through my frame.

“What is to become of the second boy?” said the clergyman, in a low whisper, but which, by some strange fatality, struck forcibly on my ear.

“It’s not much matter,” replied Basset, still lower; “for the present he goes home with me. Tom, I say, you come back with me to-day.”

“No,” said I, boldly; “I’ll go home again.”

“Home!” repeated he, with a scornful laugh,—“home I And where may that be, youngster?”

“For shame, Basset!” said the clergyman; “don’t speak that way to him. My little man, you can’t go home today. Mr. Basset will take you with him for a few days, until your late father’s will is known, and his wishes respecting you.”

“I’ll go home, sir!” said I, but in a fainter tone, and with tears in my eyes.

“Well, well! let him do so for to-day; it may relieve his poor heart. Come, Basset, I ‘ll take him back myself.”

I clasped his hand as he spoke, and kissed it over and over.

“With all my heart,” cried Basset. “I’ll come over and fetch him to-morrow;” and then he added, in a lower tone, “and before that you ‘ll have found out quite enough to be heartily sick of your charge.”

All the worthy vicar’s efforts to rouse me from my stupor or interest me failed. He brought me to his house, where, amid his own happy children, he deemed my heart would have yielded to the sympathy of my own age. But I pined to get back; I longed—why, I knew not—to be in my own little chamber, alone with my grief. In vain he tried every consolation his kind heart and his life’s experience had taught him; the very happiness I witnessed but reminded me of my own state, and I pressed the more eagerly to return.

It was late when he drew up to the door of the house, to which already the closed window shutters had given a look of gloom and desertion. We knocked several times before any one came, and at length two or three heads appeared at an upper window, in half-terror at the unlooked-for summons for admission.

“Good-by, my dear boy!” said the vicar, as he kissed me; “don’t forget what I have been telling you. It will make you bear your present sorrow better, and teach you to be happier when it is over.”

“Come down to the kitchen, alannah!” said the old cook, as the hall door closed; “come down and sit with us there. Sure it ‘s no wonder your heart ‘ud be low.”

“Yes, Master Tommy; and Darby “the Blast” is there, and a tune and the pipes will raise you.”

I suffered myself to be led along listlessly between them to the kitchen, where, around a huge fire of red turf, the servants of the house were all assembled, together with some neighboring cottagers; Darby “the Blast” occupying a prominent place in the party, his pipes laid across his knees as he employed himself in concocting a smoking tumbler of punch.

“Your most obadient!” said Darby, with a profound reverence, as I entered. “May I make so bowld as to surmise that my presence is n’t unsaysonable to your feelings? for I wouldn’t be contumacious enough to adjudicate without your honor’s permission.”

What I muttered in reply I know not; but the whole party were speedily reseated, every eye turned admiringly on Darby for the very neat and appropriate expression of his apology.

Young as I was and slight as had been the consideration heretofore accorded me, there was that in the lonely desolation of my condition which awakened all their sympathies, and directed all their interests towards me; and in no country are the differences of rank such slight barriers in excluding the feeling of one portion of the community from the sorrows of the others: the Irish peasant, however humble, seems to possess an intuitive tact on this subject, and to minister all the consolations in his power with a gentle delicacy that cannot be surpassed.

The silence caused by my appearing among them was unbroken for some time after I took my seat by the fire; and the only sounds were the clinking of a spoon against the glass, or, the deep-drawn sigh of some compassionate soul, as she wiped a stray tear from the corner of her eye with her apron.

Darby alone manifested a little impatience at the sudden change in a party where his powers of agreeability had so lately been successful, and fidgeted on his chair, unscrewed his pipes, blew into them, screwed them on again, and then slyly nodded over to the housemaid, as he raised his glass to his lips.

“Never mind me,” said I to the old cook, who, between grief and the glare of a turf fire, had her face swelled out to twice its natural size,—“never mind me, Molly, or I ‘ll go away.”

“And why would you, darlin’? Troth, no! sure there ‘s nobody feels for you like them that was always about you. Take a cup of tay, alannah; it ‘ll do you good.”

“Yes, Master Tom,” said the butler; “you never tasted anything since Tuesday night.”

“Do, sir, av ye plaze!” said the pretty housemaid, as she stood before me, cup in hand.

“Arrah! what’s tay?” said Darby, in a contemptuous tone of voice. “A few dirty laves, with a drop of water on top of them, that has neither beatification nor invigoration. Here ‘s the fons animi!” said he, patting the whisky bottle affectionately. “Did ye ever hear of the ancients indulging in tay? D’ye think Polyphamus and Jupither took tay?”

The cook looked down abashed and ashamed.

“Tay’s good enough for women,—no offence, Mrs. Cook!—but you might boil down Paykin, and it’d never be potteen. Ex quo vis ligno non fit Mercurius,—‘You can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear.’ That’s the meaning of it; ligno ‘s a sow.”

Heaven knows I was in no mirthful mood at that moment; but I burst into a fit of laughing at this, in which, from a sense of politeness, the party all joined.

“That’s it, acushla!” said the old cook, as her eyes sparkled with delight; “sure it makes my heart light to see you smilin’ again. Maybe Darby would raise a tune now, and there ‘s nothing equal to it for the spirits.”

“Yes, Mr. M’Keown,” said the housemaid; “play ‘Kiss me twice!’ Master Tom likes it.”

“Devil a doubt he does!” replied Darby, so maliciously as to make poor Kitty blush a deep scarlet; “and no shame to him! But you see my fingers is cut. Master Tom, and I can’t perform the reduplicating intonations with proper effect.”

“How did that happen. Darby?” said the butler.

“Faix, easy enough. Tim Daly and myself was hunting a cat the other evening, and she was under the dhresser, and we wor poking her with a burnt stick and a raypinghook, and she somehow always escaped us, and except about an inch of her tail, that we cut off, there was no getting at her; and at last I hated a toastin’-fork and put it in, when out she flew, teeth and claws, at me. Look, there ‘s where she stuck her thieving nails into my thumb, and took the piece clean out. The onnatural baste!”

“Arrah!” said the old cook, with a most reflective gravity, “there ‘s nothing so treacherous as a cat! “—a moral to the story which I found met general assent among the whole company.

“Nevertheless,” observed Darby, with an air of ill-dissembled condescension, “if it isn’t umbrageous to your honor, I ‘ll intonate something in the way of an ode or a canticle.”

“One of your own. Darby,” said the butler, interrupting.

“Well, I’ve no objection,” replied Darby, with an affected modesty; “for you see, master, like Homer, I accompany myself on the pipes, though—glory be to God!—I’m not blind. The little thing I ‘ll give you is imitated from the ancients—like Tibullus or Euthropeus—in the natural key.”

Mister M’Keown, after this announcement, pushed his empty tumbler towards the butler with a significant glance gave a few preparatory grunts with the pipes, followed by a long dolorous quaver, and then a still more melancholy cadence, like the expiring bray of an asthmatic jackass; all of which sounds, seeming to be the essential preliminaries to any performance on the bagpipes, were listened to with great attention by the company. At length, having assumed an imposing attitude, he lifted up both elbows, tilted his little finger affectedly up, dilated his cheeks, and began the following to the well-known air of “Una:”—

MUSIC. Of all the arts and sciences, ‘T is music surely takes the sway; It has its own appliances To melt the heart or make it gay. To raise us, Or plaze us, There ‘s nothing with it can compare; To make us bowld, Or hot or cowld, Just as suits the kind of air. There ‘s not a woman, man, or child. That has n’t felt its powers too; Don’t deny it!—when you smiled Your eyes confess’d, that so did you. The very winds that sigh or roar; The leaves that rustle, dry and sear; The waves that beat upon the shore,— They all are music to your ear. It was of use To Orpheus,— He charmed the fishes in the say; So everything Alive can sing,— The kettle even sings for tay! There’s not a woman, man, or child. That hau n’t felt its power too; Don’t deny it!—when you smiled Your eyes confess’d, that so did you.

I have certainly since this period listened to more brilliant musical performances, but for the extent of the audience, I do not think it was possible to reap a more overwhelming harvest of applause. Indeed, the old cook kept repeating stray fragments of the words to every air that crossed her memory for the rest of the evening; and as for Kitty, I intercepted more than one soft glance intended for Mister M’Keown as a reward for his minstrelsy.

Darby, to do him justice, seemed fully sensible of his triumph, and sat back in his chair and imbibed his liquor like a man who had won his laurels, and needed no further efforts to maintain his eminent position in life.

As the wintry wind moaned dismally without, and the leafless trees shook and trembled with the cold blast, the party drew in closer to the cheerful turf fire, with that sense of selfish delight that seems to revel in the contrast of indoor comfort with the bleakness and dreariness without.

“Well, Darby,” said the butler, “you weren’t far wrong when you took my advice to stay here for the night; listen to how it ‘s blowing.”

“That ‘s hail!” said the old cook, as the big drops came pattering down the chimney, and hissed on the red embers as they fell. “It ‘s a cruel night, glory be to God!” Here the old lady blessed herself,—a ceremony which the others followed.

“For all that,” said Darby, “I ought to be up at Crocknavorrigha this blessed evening. Joe Neale was to be married to-day.”

“Joe! is it Joe?” said the butler.

“I wish her luck of him, whoever she is!” added the cook.

“Faix, and he’s a smart boy!” chimed in the housemaid, with something not far from a blush as she spoke.

“He was a raal devil for coortin’, anyhow!” said the butler.

“It’s just for peace he’s marrying now, then,” said Darby; “the women never gave him any quietness. Just so, Kitty; you need n’t be looking cross that way,—it ‘s truth I’m telling you. They were always coming about him, and teasing him, and the like, and he could n’t bear it any longer.”

“Arrah, howld your prate!” interrupted the old cook, whose indignation for the honor of the sex could not endure more. “He’s the biggest liar from this to himself; and that same ‘s not a small word. Darby M’Keown.”

There was a pointedness in the latter part of this speech which might have led to angry consequences, had I not interposed by asking Mr. M’Keown himself if he ever was in love.

“Arrah, it ‘s wishing it, I am, the same love. Sure my back and sides is sore with it; my misfortunes would fill a book. Did n’t I bind myself apprentice to a carpenter for love of Molly Scraw, a niece he had, just to be near her and be looking at her; and that ‘s the way I shaved off the top of my thumb with the plane. By the mortial, it was near killing me. I usedn’t to eat or drink; and though I was three years at the thrade, faix, at the end of it, I could n’t tell you the gimlet from the handsaw!”

“And you wor never married, Mister M’Keown?” said Kitty.

“Never, my darling, but often mighty near it. Many ‘s the quare thing happened to me,” said Darby, meditatingly; “and sure if it was n’t my guardian angel, or something of the kind, prevented it, I ‘d maybe have more wives this day than the Emperor of Roossia himself.”

“Arrah, don’t be talking!” grunted out the old cook, whose passion could scarcely be restrained at the boastful tone Mister M’Keown assumed in descanting on his successes.

“There was Biddy Finn,” continued Darby, without paying any attention to the cook’s interruption; “she might be Mrs. M’Keown this day, av it wasn’t for a remarkable thing that happened.”

“What was that?” said Kitty, with eager curiosity.

“Tell us about it. Mister M’Keown,” said the butler.

“The devil a word of truth he’ll tell you,” grumbled the cook, as she raked the ashes with a stick.

“There ‘s them here does not care for agreeable intercoorse,” said Darby, assuming a grand air.

“Come, Daxby; I ‘d like to hear the story,” said I.

After a few preparatory scruples, in which modesty, offended dignity, and conscious merit struggled, Mr. M’Keown began by informing us that he had once a most ardent attachment to a certain Biddy Finn, of Ballyclough,—a lady of considerable personal attractions, to whom for a long time he had been constant, and at last, through the intervention of Father Curtin, agreed to marry. Darby’s consent to the arrangements was not altogether the result of his reverence’s eloquence, nor indeed the justice of the case; nor was it quite owing to Biddy’s black eyes and pretty lips; but rather to the soul-persuading powers of some fourteen tumblers of strong punch which he swallowed at a séance in Biddy’s father’s house one cold evening in November, after which he betook himself to the road homewards, where—But we must give his story in his own words:

“Whether it was the prospect of happiness before me, or the potteen,” quoth Darby, “but so it was,—I never felt a step of the road home that night, though it was every foot of five mile. When I came to a stile, I used to give a whoop, and over it; then I’d run for a hundred yards or two, flourish my stick, cry out, ‘Who ‘ll say a word against Biddy Finn?’ and then over another fence, flying. Well, I reached home at last, and wet enough I was; but I did n’t care for that. I opened the door and struck a light; there was the least taste of kindling on the hearth, and I put some dry sticks into it and some turf, and knelt down and began blowing it up.

“‘Troth,’ says I to myself, ‘if I wor married, it isn’t this way I’d be,—on my knees like a nagur; but when I ‘d come home, there ‘ud be a fine fire blazin’ fornint me, and a clean table out before it, and a beautiful cup of tay waiting for me, and somebody I won’t mintion, sitting there, looking at me, smilin’.’

“‘Don’t be making a fool of yourself, Darby M’Keown,’ said a gruff voice near the chimley.

“I jumped at him, and cried out, ‘Who ‘s that?’ But there was no answer; and at last, after going round the kitchen, I began to think it was only my own voice I heard; so I knelt down again, and set to blowing away at the fire.

“‘And it’s yerself, Biddy,’ says I, ‘that would be an ornament to a dacent cabin; and a purtier leg and foot—’

“‘Be the light that shines, you’re making me sick. Darby M’Keown,’ said the voice again.

“‘The heavens be about us!’ says I, ‘what ‘s that? and who are you at all?’ for someways I thought I knew the voice.

“‘I ‘m your father!’ says the voice.

“‘My father!’ says I. ‘Holy Joseph, is it truth you ‘re telling me?’

“‘The divil a word o’ lie in it,’ says the voice. ‘Take me down, and give me an air o’ the fire, for the night ‘s cowld.’

“‘And where are you, father,’ says I, ‘av it’s plasing to ye?’

“‘I ‘m on the dhresser,’ says he. ‘Don’t you see me?’

“‘Sorra bit o’ me. Where now?’

“‘Arrah, on the second shelf, next the rowling-pin. Don’t you see the green jug?—that’s me.’

“‘Oh, the saints in heaven be about us!’ says I; ‘and are you a green jug?’

“‘I am,’ says he; ‘and sure I might be worse. Tim Healey’s mother is only a cullender, and she died two years before me.’

“‘Oh! father, darlin’,’ says I, ‘I hoped you wor in glory; and you only a jug all this time!’

“‘Never fret about it,’ says my father; ‘it ‘s the transmogrification of sowls, and we ‘ll be right by and by. Take me down, I say, and put me near the fire.’

“So I up and took him down, and wiped him with a clean cloth, and put him on the hearth before the blaze.

“‘Darby,’ says he, ‘I’m famished with the druth. Since you took to coortin’ there ‘s nothing ever goes into my mouth; haven’t you a taste of something in the house?’

“I wasn’t long till I hated some wather, and took down the bottle of whiskey and some sugar, and made a rousing jugful, as strong as need be.

“‘Are you satisfied, father?’ says I.

“‘I am,’ says he; ‘you ‘re a dutiful child, and here ‘s your health, and don’t be thinking of Biddy Finn,’

“With that my father began to explain how there was never any rest nor quietness for a man after he married,—more be token, if his wife was fond of talking; and that he never could take his dhrop of drink in comfort afterwards.

“‘May I never,’ says he, ‘but I ‘d rather be a green jug, as I am now, than alive again wid your mother. Sure it ‘s not here you’d be sitting to-night,’ says he, ‘discoorsing with me, av you wor married; devil a bit. Fill me,’ says my father, ‘and I ‘ll tell you more.’

“And sure enough I did, and we talked away till near daylight; and then the first thing I did was to take the ould mare out of the stable, and set off to Father Curtin, and towld him all about it, and how my father would n’t give his consent by no means.

“‘We’ll not mind the marriage,’ says his rivirence; ‘but go back and bring me your father,—the jug, I mean,—and we ‘ll try and get him out of trouble; for it ‘s trouble he ‘s in, or he would n’t be that way. Give me the two pound ten,’ says the priest; ‘you had it for the wedding, and it will be better spent getting your father out of purgatory than sending you into it. ‘”

“Arrah, aren’t you ashamed of yourself?” cried the cook, with a look of ineffable scorn, as he concluded.

“Look now,” said Darby, “see this; if it is n’t thruth—”

“And what became of your father?” interrupted the butler.

“And Biddy Finn, what did she do?” said the housemaid.

Darby, however, vouchsafed no reply, but sat back in his chair with an offended look, and sipped his liquor in silence.

A fresh brew of punch under the butler’s auspices speedily, however, dispelled the cloud that hovered over the conviviality of the party; and even the cook vouchsafed to assist in the preparation of some rashers, which Darby suggested were beautiful things for the thirst at this hour of the night; but whether in allaying or exciting it, he did n’t exactly lay down. The conversation now became general; and as they seemed resolved to continue their festivities to a late hour, I took the first opportunity I could, when unobserved, to steal away and return to my own room.

No sooner alone again than all the sorrow of my lonely state came back upon me; and as I laid my head on my pillow, the full measure of my misery flowed in upon my heart, and I sobbed myself to sleep.

The violent beating of the rain against the glass, and the loud crash of the storm as it shook the window-frames or snapped the sturdy branches of the old trees, awoke me. I got up, and opening the shutters, endeavored to look out; but the darkness was impenetrable, and I could see nothing but the gnarled and grotesque forms of the leafless trees dimly marked against the sky, as they moved to and fro like the arms of some mighty giant. Masses of heavy snow melted by the rain fell at intervals from the steep roof, and struck the ground beneath with a low sumph like thunder. A grayish, leaden tinge that marked the horizon showed it was near daybreak; but there was nought of promise in this harbinger of morning. Like my own career, it opened gloomily and in sadness: so felt I at least; and as I sat beside the window, and strained my eyes to pierce the darkening storm, I thought that even watching the wild hurricane without was better than brooding over the sorrows within my own bosom.

How long I remained thus I know not; but already the faint streak that announces sunrise marked the dull-colored sky, when the cheerful sounds of a voice singing in the room underneath attracted me. I listened, and in a moment recognized the piper. Darby M’Keown. He moved quickly about, and by his motions I could collect that he was making preparations for his journey.

If I could venture to pronounce, from the merry tones of his voice and the light elastic step with which he trod the floor, I certainly would not suppose that the dreary weather had any terror for him. He spoke so loud that I could catch a great deal of the dialogue he maintained with himself, and some odd verses of the song with which from time to time he garnished his reflections.

“Marry, indeed! Catch me at it—nabocklish—with the countryside before me, and the hoith of good eating and drinking for a blast of the chantre. Well, well! women ‘s quare craytures anyway.

‘Ho, ho! Mister Ramey, No more of your blarney, I ‘d have yoa not make so free; You may go where you plaze. And make love at your ease. But the devil may have you for me.’

Very well, ma’am. Mister M’Keown is your most obedient,—never say it twice, honey; and isn’t there as good fish, eh?—whoop!

‘Oh! my heart is unazy. My brain is run crazy, Sure it ‘s often I wish I was dead; ‘Tis your smile now so sweet! Now your ankles and feet. That ‘s walked into my heart, Molly Spread! Tol de rol, de rol, oh!’

Whew! thttt ‘s rain, anyhow. I would n’t mind it, bad as it is, if I hadn’t the side of a mountain before me; but sure it comes to the same in the end. Catty Delany is a good warrant for a pleasant evening; and, please God, I ‘ll be playing ‘Baltiorum’ beside the fire there before this time to-night.

‘She ‘d a pig and boneens. And a bed and a dresser. And a nate little room For the father confessor; With a cupboard and curtains, and something, I ‘m towld. That his riv’rance liked when the weather was cowld. And it ‘s hurroo, hurroo! Biddy O’Rafferty!’

After all, aix, the priest bates us out. There ‘s eight o’clock now, and I’m not off; devil a one’s stirring in the house either. Well, I believe I may take my leave of it; sorrow many tunes of the pipes it’s likely to hear, with Tony Basset over it. And my heart ‘s low when I think of that child there. Poor Tom! and it was you liked fun when you could have it.”

I wanted but the compassionate tone in which these few words were spoken to decide me in a resolution that I had been for some time pondering over. I knew that ere many hours Basset would come in search of me; I felt that, once in his power, I had nothing to expect but the long-promised payment of his old debt of hatred to me. In a few seconds I ran over with myself the prospect of misery before me, and determined at once, at every hazard, to make my escape. Darby seemed to afford me the best possible opportunity for this purpose; and I dressed myself, therefore, in the greatest haste, and throwing whatever I could find of my wardrobe into my carpet-bag, I pocketed my little purse, with all my worldly wealth,—some twelve or thirteen shillings,—and noiselessly slipped downstairs to the room beneath. I reached the door at the very moment Darby opened it to issue forth. He started back with fear, and crossed himself twice.

“Don’t be afraid. Darby,” said I, uneasy lest he should make any noise that would alarm the others; “I want to know which road you are travelling this morning.”

“The saints be about us, but you frightened me. Master Tommy; though, intermediately, I may obsarve, I ‘m by no ways timorous. I ‘m going within two miles of Athlone.”

“That’s exactly where I want to go. Darby; will you take me with you?” for at the instant Captain Bubbleton’s address flashed on my mind, and I resolved to seek him out and ask his advice in my difficulties.

“I see it all,” replied Darby, as he placed the tip of his finger on his nose. “I conceive your embarrassments,—you’re afraid of Basset; and small blame to you. But don’t do it. Master Tommy,—don’t do it, alannah! that ‘s the hardest life at all.”

“What?” said I, in amazement.

“To ‘list! Sure I know what you’re after. Faix, it would sarve you better to larn the pipes.”

I hastened to assure Darby of his error; and in a few words informed him of what I had overheard of Basset’s intentions respecting me.

“Make you an attorney!” said Darby, interrupting me abruptly; “an attorney! There’s nothing so mean as an attorney. The police is gentlemen compared to them,—they fight it out fair like men; but the other chaps sit in a house planning and contriving mischief all day long, inventing every kind of wickedness, and then getting people to do it. See, now, I believe in my conscience the devil was the first attorney, and it was just to serve his own ends that he bred a ruction between Adam and Eve. But whisht! there’s somebody stirring. Are you for the road?”

“Yes, Darby; my mind’s made up.”

Indeed, his own elegant eulogium on legal pursuits assisted my resolution, and filled my heart with renewed disgust at the thought of such a guardian as Tony Basset.

We walked stealthily along the gloomy passages, traversed the old hall, and noiselessly withdrew the heavy bolts and the great chain that fastened the door. The rain was sweeping along the ground in torrents, and the wind dashed it against the window panes in fitful gusts. It needed all our strength to close the door after us against the storm, and it was only after several trials that we succeeded in doing so. The hollow sound of the oak door smote upon my heart as it closed behind me; in an instant the sense of banishment, of utter destitution, was present to my mind. I turned my eyes to gaze upon the old house,—to take my last farewell of it forever! Gloomy as my prospect was, my sorrow was less for the sad future than for the misery of the moment.

“No, Master Tom! no, you must go back,” said Darby, who watched with a tender interest the sickly paleness of my cheek, and the tottering uncertainty of my walk.

“No, Darby,” said I, with an effort at firmness; “I’ll not look round any more.” And bending my head against the storm, I stepped out boldly beside my companion. We walked on without speaking, and soon left the neglected avenue and ruined gate lodge behind us, as we reached the highroad that led to Athlone.

Darby, who only waited to let my first burst of sorrow find its natural vent, no sooner perceived from my step and the renewed color of my cheek that I had rallied my courage once more, than he opened all his stores of agreeability, which, to my inexperience in such matters, were by no means inconsiderable. Abandoning at once all high-flown phraseology,—which Mr. M’Keown, I afterwards remarked, only retained as a kind of gala suit for great occasions,—he spoke freely and naturally. Lightening the way with many a story,—now grave, now gay,—he seemed to care little for the inclemency of the weather, and looked pleasantly forward to a happy evening as an ample reward for the present hardship.

“And the captain, Master Tom; you say he’s an agreeable man?” said Darby, alluding to my late companion on the coach, whose merits I was never tired of recapitulating.

“Oh, delightful! He has travelled everywhere, and seems to know everybody and everything. He ‘s very rich, too; I forget how many houses he has in England, and elephants without number in India.”

“Faix, you were in luck to fall in with him!” observed Darby.

“Yes, that I was I I ‘m sure he ‘ll do something for me; and for you too, Darby, when he knows you have been so kind to me.”

“Me! What did I do, darling? and what could I do, a poor piper like me? Wouldn’t it be honor enough for me if a gentleman’s son would travel the road with me? Darby M’Keown’s a proud man this day to have you beside him.”

A ruined cabin in the road, whose blackened walls and charred timbers denoted its fate, here attracted my companion’s attention. He stopped for a second or two to look on it; and then, kneeling down, he muttered a short prayer for the eternal rest of some one departed, and taking up a stone, he threw it on a heap of similar ones which lay near the doorside.

“What happened there, Darby?” said I, as he resumed his way.

“They wor out in the thrubles!” was his only reply, as he cast a glance behind, to perceive if any one had remarked him.

Though he made no further allusion to the fate of those who once inhabited the cabin, he spoke freely of his own share in the eventful year of ‘Ninety-eight’ justifying, as it then seemed to me, every step of the patriotic party, and explaining the causes of their unsuccess so naturally and so clearly that I could not help following with interest every detail of his narrative, and joining in his regrets for the unexpected and adverse strokes fortune dealt upon them. As he warmed with his subject, he spoke of France with an enthusiasm that I soon found contagious. He told me of the glorious career of the French armies in Italy and Austria; and of that wonderful man, of whom I then heard for the first time, as spreading a halo of victory over his nation,—contrasting, as he went on, the rewards which awaited heroism and bravery in that service with the purchased promotion in ours, artfully illustrating his position by a reference to myself, and what my fortunes would have been if born under that happier sky. “No elder brother there,” said he, “to live in affluence, while the younger ones are turned out to wander on the wide world, houseless and penniless. And all these things we might have done, had we been but true to ourselves.” I drank in all he said with avidity. The bearing of his arguments on my own fortunes gave them an interest and an apparent truth my young mind eagerly devoured; and when he ceased to speak, I pondered over all he told me in a spirit that left its impress on my whole future life.

It was a new notion to me to connect my own fortunes with anything in the political condition of the country; and while it gave my young heart a kind of martyred courage, it set my brain a-thinking on a class of subjects which never before possessed any interest for me. There was a flattery, too, in the thought that I owed my straitened circumstances less to any demerits of my own, than to political disabilities. The time was well chosen by my companion to instil his doctrines into my heart. I was young, ardent, enthusiastic; my own wrongs had taught me to hate injustice and oppression; my condition had made me feel, and feel bitterly, the humiliation of dependence; and if I listened with eager curiosity to every story and every incident of the bygone Rebellion, it was because the contest was represented to me as one between tyranny on one side and struggling liberty on the other. I heard the names of those who sided with the insurgent party extolled as the great and good men of their country; their ancient families and hereditary claims furnishing a contrast to many of the opposite party, whose recent settlement in the island and new-born aristocracy were held up in scoff and derision. In a word, I learned to believe that the one side was characterized by cruelty, oppression, and injustice; the other, conspicuous only for endurance, courage, patriotism, and truth. What a picture was this to a mind like mine! and at a moment, too, when I seemed to realize in my own desolation an example of the very sufferings I heard of!

If the portrait McKeown drew of Ireland was sad and gloomy, he painted France in colors the brightest and most seductive. Dwelling less on the political advantages which the Revolution had won for the popular party, he directed my entire attention to the brilliant career of glory the French army had followed; the triumphant success of the Italian campaign; the war in Germany; and the splendor of Paris, which he represented as a very paradise on earth; but above all, he dwelt on the character and achievements of the First Consul, recounting many anecdotes of his early life, from the period when he was a schoolboy at Brienne to the hour when he dictated the conditions of peace to the oldest monarchies of Europe, and proclaimed war with the voice of one who came as an avenger.

I drank in every word he spoke with avidity. The very enthusiasm of his manner was contagious; I felt my heart bound with rapturous delight at some hardy deed of soldierlike daring, and conceived a kind of wild idolatry for the man who seemed to have infused his own glorious temperament into the mighty thousands around him, and converted a whole nation into heroes.

Darby’s information on all these matters—which seemed to me something miraculous—had been obtained at different periods from French emissaries who were scattered through Ireland; many of them old soldiers who had served in the campaigns of Egypt and Italy.

“But sure, if you ‘d come with me, Master Tom, I could bring you where you’ll see them yourself; and you could talk to them of the battles and skirmishes, for I suppose you spake French.”

“Very little. Darby. How sorry I am now that I don’t know it well.”

“No matter; they’ll soon teach you, and many a thing besides. There ‘s a captain I know of, not far from where we are this minute, could learn you the small sword,—in style, he could. I wish you saw him in his green uniform with white facings, and three elegant crosses upon it that General Bonaparte gave him with his own hands; he had them on one Sunday, and I never see’d anything equal to it.”

“And are there many French officers hereabouts?”

“Not now; no, they’re almost all gone. After the rising they went back to France, except a few. Well, there’ll be call for them again, please God.”

“Will there be another Rebellion, then, Darby?”

As I put this question fearlessly, and in a voice loud enough to be heard at some distance, a horseman, wrapped up in a loose cloth cloak, was passing. He suddenly pulled up short, and turning his horse round, stood exactly opposite to the piper. Darby saluted the stranger respectfully, and seemed desirous to pass on; but the other, turning round in his saddle, fixed a stern look on him, and he cried out,—

“What! at the old trade, M’Keown. Is there no curing you, eh?”

“Just so, major,” said Darby, assuming a tone of voice he had not made use of the entire morning; “I ‘m conveying a little instrumental recreation.”

“None of your damned gibberish with me. Who ‘s that with you?”

“He ‘s the son of a neighbor of mine, your honor,” said Darby, with an imploring look at me not to betray him. “His father ‘s a schoolmaster,—a philomath, as one might say.”

I was about to contradict this statement bluntly, when the stranger called out to me,—

“Mark me, young sir, you ‘re not in the best of company this morning, and I recommend you to part with your friend as soon as may be. And you,” said he, turning to Darby, “let me see you in Athlone at ten o’clock to-morrow. D’ ye hear me?”

The piper grew pale as death as he heard this command, to which he only responded by touching his hat in silence; while the horseman, drawing his cloak around, dashed his spurs into his beast’s flanks, and was soon out of sight. Darby stood for a moment or two looking down the road, where the stranger had disappeared; a livid hue colored his cheek, and a tremulous quivering of his under-lip gave him the appearance of one in ague.

“I’ll be even with ye yet,” muttered he between his clenched teeth; “and when the hour comes—”

Here he repeated some words in Irish with a vehemence of manner that actually made my blood tingle; then suddenly recovering himself, he assumed a kind of sickly smile. “That’s a hard man, the major.”

“I’m thinking,” said Darby, after a pause of some minutes,—“I ‘m thinking it ‘s better for you not to go into Athlone with me; for if Basset wishes to track you out, that ‘ll be the first place he ‘ll try. Besides, now that the major has seen you, he’ll never forget you.”